Water in Cities

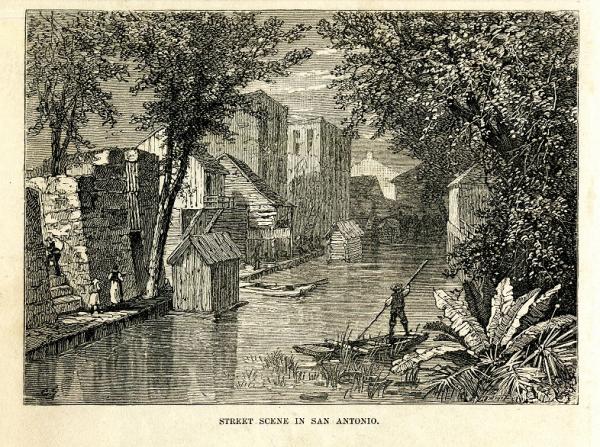

Every city's story is written in water as well as in land and people (fig. 1).

New York was planted on one of the world's great natural harbors, where the Hudson provided deepwater access far into the interior. The fertile estuary offered a seafood bounty to the Lenape, then Dutch and then British settlers. New Orleans, the "impossible but inevitable city" in the words of Peirce Lewis, commanded the mouth of the Mississippi, the continent's great river, but no part of its site stood above the highest floods of that river. Chicago, too, began as a continentally strategic node, where a brief portage and later a short canal connected the two great interior water pathways of French North America, the Mississippi, and the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence. And Los Angeles, strangely to our ears today, was located for its abundant water supply, where a subterranean rock formation forced an underground river to the surface even in the driest years.

The origin stories are different; without water they are untellable. As the stories continue, water remains central.

New York ascended to continental primacy first through the innovation of "packet ships" sailing to European ports on set schedules, and then by building the Erie Canal to bring the Great Lakes into its hinterland. When its water supply became a source of disease (and horses from Philadelphia refused to drink it), New York incorporated as a city to finance and build the Croton Aqueduct, beginning a public water system of such purity that to this day it requires no treatment.

New Orleans built levees that protected the city, often by flooding its neighbors. In the early twentieth century, the largest pumps in the world enabled development of the land at the bottom of the "bowl" within the levees. That was good for the city until it was bad, in 1965 with Hurricane Betsy and again fifty years later with Hurricane Katrina (fig. 2).

Los Angeles grew far beyond the capacity of its reliable river, through the water imperialism of taking first from the Owens Valley (fig. 3), and eventually through the Colorado River from as far as Wyoming. The seemingly de-watered Los Angeles River occasionally came back to life with a vengeance through catastrophic flooding, answered in the 1940s with a 51-mile-long concrete channel that has become a canonical dystopian image of the city.

Chicago's phenomenal growth was fueled by railroads. This does not sound like a water story, but the railroad network was shaped by New York financiers already invested in Chicago through Erie Canal commerce, and Chicago could arbitrage shipping rates by land or by water in a way unavailable to its competitors. Chicago engaged in its own imperialism of water flows, reversing the direction of the Chicago River to send wastes away from its own water supply, toward St. Louis.

My own current research examines the cultural landscapes that resulted from surface water conveyance through irrigation cities (see "Digging Ditches," Platform 2019–2020). Earlier in my career I worked on the history of ports and urban landmaking, and of navigation and power canals in the Northeast. My work encompasses not just the great systems that make and shape cities, but the expressions of water in landscape and culture.

These subjects, I realized, could form a course that crosses every discipline in the School of Architecture—something I am surprised is not more common. Constructing the syllabus was an exercise in too many choices. Chronology? Geography? I arrived at something like functions or systems—drainage, consumption, waste, transportation, amenity. These transcend all times and places, unfolding in different ways at different times. And most importantly for the course's theme, these systems collide and intersect in complex ways that constitute the water biography of each city. I launched this course in fall 2022 as “History of Water in Cities.”

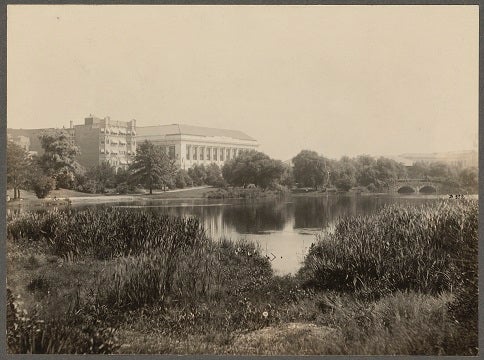

Students responded with tremendous enthusiasm, and some took the course in directions I hadn't anticipated. Students explored their hometowns or other cities they found interesting. Jonathan Shuster (MSCRP ’23) wrote about the culture of rain in Seattle—a subject that includes the elusive view of Mount Rainier, imprinted on urban form and on the collective psyche of Seattleites. Julia Manion (MSSD ’23) recounted the long history of blue-green infrastructure, from Frederick Law Olmsted's Back Bay Fens in Boston (fig. 4) through Ian McHarg's Design with Nature to the present. Christopher Griffith (BArch ’23) described the experience of tsunamis (that's right, plural) in Hilo, Hawaii, and its productive outcome in an international warning system based on sensors across the Pacific. Claire Kelly (MLA ’24) analyzed the transition, in urban public recreational water, from pools to splashpads. And Connor Phillips (PhD CRP student) wrote about water control systems, from ancient hydraulic automatons, to nineteenth-century telegraphic connections to reservoirs that supplied Lowell's mill turbines, to the AI systems that are the subject of his own research. Many students started from present-day issues and found that these had long histories, with failures and successes at solutions and adaptations.

Large and small themes begin to emerge.

Over the long sweep of history, as transportation improved faster on land than on water, water's place in urban form tended to move from path to edge.

Cities almost invariably built water supply first, and sewers later. Only after water mains delivered, and toilets flushed, did cities consider the possible need for sewage systems as a category of public infrastructure. This does not speak highly of our ability to foresee and shape the future.

Water bodies served everywhere as sinks for wastes of all kinds. Sewage entered rivers that carried it away—"away” sometimes referring to the water supply of downstream communities. People used refuse, ash, and debris to fill wetlands and extend shorelines. Water bodies got smaller and cities got bigger; soon they swam in their own filth. Urban shorelines and streambanks came to be seen as repellent places, their inhabitants determined through lack of choice.

Water quality became an environmental issue long before air quality did, with local successes in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and then dramatic national successes beginning later in the twentieth century. As waterways got cleaner, they became amenities in the hearts of cities, as they had long been at out-of-town beaches and shores.

Water has served as an amenity for millennia through fountains and gardens, but in North American cities any design of water at an urban scale at first served practical rather than aesthetic ends. This changed in the nineteenth century, with ornamental water features and eventually whole shorelines and stream corridors designed as parts of park systems. More recently the scale has grown still larger, but "design" at a metropolitan scale is a more diffuse and distributed process.

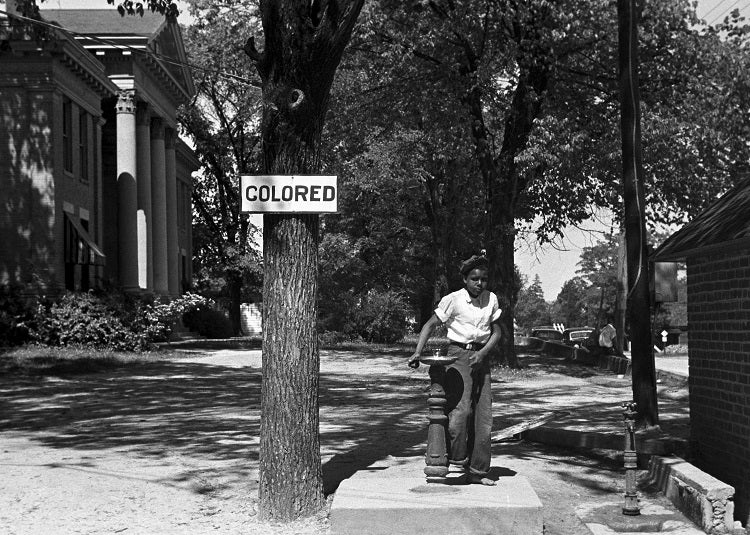

For two centuries, the places where we communally immerse our bodies—baths, beaches, and pools—have become sites for the most fervid expression of social distinctions. Over time these have varied: first class, then sex, then race (fig. 5). Water also provides venues for less conflict-ridden social interactions. In the nineteenth century both Los Angeles and San Antonio had a canal-side path known as "Lovers' Lane"; in twentieth-century New York, loci of gay life included bathhouses, abandoned piers on the Hudson, and beaches at Fire Island.

When we talk about climate change we are often talking about water, about disruptions that make less of it where it is needed and more where it is not. Water stresses ripple through other networks: power generation disrupted by lack of water to turn turbines or to cool generators, transportation halted by low water in rivers, food supplies stunted by drought or by flood, sometimes both in a single place and year. We make urban heat islands with asphalt and rooftops, yes, but also with water stresses that reduce the availability or capacity of trees to amend microclimates.

We have constructed both these needs and these disruptions, and we have done so over centuries. Water flows are the most elemental, most essential, most ancient of urban systems. They have shaped many other networks, sometimes invisibly through cadastral or administrative patterns. We think of land as a separate category, yet how much is urban land shaped by its proximity to, or isolation by, bodies of water? By access to good water or hazards borne by bad water? By its susceptibility to flooding, or by its long-ago origins as fill?

This year's class will soon present its work.

This article originally appeared in the 2023-2024 edition of Platform, "Civics and Placemaking." To view the original version, including end notes, visit: https://soa.utexas.edu/publications/platform/platform-civics-and-placem…

Fig. 1: Muslin-draped bathing houses float at the foot of gardens, and the limpid little stream is in high favor as a refuge during the heated term." Frank H. Taylor, "A Journey through Texas," Harper's New Monthly Magazine, October 1879

FACULTY:

Michael Holleran