In Ditched Schemes, Designs That Didn’t Make The Cut Get A Second Look

As designers and as academics, we have developed a working relationship with rejection and failure. We believe this deserves more discussion.

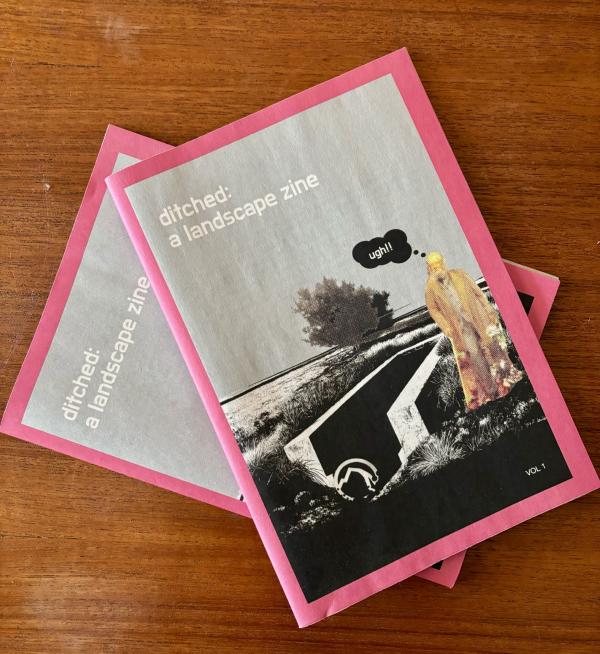

In September 2023, we offered an open call to landscape architects to share their unselected projects in a zine. As we waded into the project, we learned there’s a tremendous interest in uncovering stories of how we navigate risk and refocus on the projects that got away. We compiled a small archive of unrealized projects on social media, and this month we are releasing the first issue of a zine titled Ditched Schemes along with a series of podcast interviews. Ditched Schemes is a platform for highlighting the relationship we have with our work, while uncovering ideas that have not yet found their audience. For us, this project brings up pressing questions about what landscape architecture considers success.

Our archive research began with general curiosity: What ideas and design approaches left unrealized in the past might be worth revisiting? How have proposals from designers at the start of their careers evolved over time? But compiling our archive raised other questions as well: Who can fail publicly, and how do identity and positionality affect the risks we are each able to take?

As students, we learned about some notorious failed schemes: OMA’s entry for the 1982 Parc de la Villette competition in Paris, the 1999 competition short list for Downsview Park in Toronto, or the incomplete implementation of the 1851 Andrew Jackson Downing plan for the National Mall in Washington, D.C. These projects may not exist as concrete forms and growing vegetation, but they live on in articles, course lectures, and conversations that still capture the imagination of what might have been. In class discussions, they illustrated critical turning points in landscape architecture history. It is inspiring to imagine the many alternative proposals to projects that we know well as built work. Through Ditched Schemes, we are daylighting those alternatives for reconsideration.

We began by looking for trends in discussions around the competition as a design relic. In 1993, an article by Eve Kahn (“The Jury’s Still Out,” LAM, August 1993) reflected on a decade of design competitions with comments from participants. The article noted the challenge of conveying landscape-led designs to juries who tended to value the clear image and symbol of an architectural response to a prompt. In 2003, Team TerraGRAM’s submission for the High Line competition took on some of the bias toward proposals that insert structures and permanent objects over projects that amplify existing site dynamics. The images highlight the emergent qualities of the High Line and recognized the landscape as “full,” with a ruderal ecology and as a site of social gathering. In hand-drawn sections, the proposal confronted the idea of a site as an “open” space awaiting program and framed an approach that sustains and celebrates this wild, urban landscape.

Twenty years later, coverage of recent competition entries continues to emphasize architectural elements over the landscape designs that offer public space and connect to urban fabric. How can we strengthen recognition and understanding of landscape-driven responses? Though the prompt for the Pulse Nightclub Memorial in Orlando, Florida, emphasized several landscape elements, the architecture is the first element to appear in our Google searches of the short list entries. In Studio Libeskind’s entry, a tower structure is grounded within a processional landscape designed by Claude Cormier + Associés (now CCxA), uniting multiple sites of significance. The groves and allées of trees create spaces of remembrance and spaces of joy that reinforce how multiple communities were affected by the 2016 Pulse Nightclub mass shooting and recognize how individuals, particularly the LGBTQIA+ community, came together to offer comfort and aid.

A reference in Kahn’s article pointed us to a competition for a Salem Witch Trials Memorial—we had to learn more! The memorialization effort, begun in 1986, was intended to remember the people who were persecuted and murdered by their community. We were captivated by the description of the concept by finalists Ann Kearsley, ASLA, and Barbara Boardman, who entered the competition while completing their MLA degrees. The design communicates the events of the trials as an experience. Visitors enter an ordered series of spaces, referencing congregation. The structure breaks down as the site is traversed, and “its elements are thrown into disarray and the foundation sinks into the earth,” the designers explained in their brief. When we corresponded with the designers (now Ann Kearsley Design and Boardman Design) to learn more, they expressed pride in their submission, and we were delighted by the mix of media used to delineate their proposal, including sketches over model photographs that they provided for Ditched Schemes.

What can we learn from looking at the variety of ways a project might be thwarted? How do we define success in a field where each project is an experiment with a multitude of uncontrollable variables and personalities? What can we learn from the projects that are built, but unmaintained, unloved, or shaped by unexpected forces? Would we prioritize different skills in school if we had more dialogue around our profession’s definitions of success and failure?

Competition entries are a fraction of the breadth of work in landscape architecture, and not everyone has the resources to devote to speculative work. For every built project, there are many alternative schemes that never made it past conceptual design and many ideas that get eliminated for cost or changes of heart. While working in design studios, we have had front-row seats to our colleagues’ excitement about a scheme, the heartbreak when it doesn’t work out, and the process of revision, again and again. We describe this tenacity to our students, and we hold on to these experiences in our own creative processes.

Salem Witch Trials Competition, Ann Kearsley, ASLA, and Barbara Boardman

This proposal was one of the three selected finalists for the Salem Witch Trials Memorial competition in 1991.

Ann Kearsley, ASLA, and Barbara Boardman approached the site by symbolizing the breakdown in society in 1692 as visitors experienced the memorial. Large stone blocks were arranged in an orderly grid until the ground shifted and broke, resulting in a slope and chaotic placement of the blocks down into the earth. Water was intended to drain across this part of the site, and the names of the victims were etched into the stone.

The competition was in response to the 1992 tercentenary of the Salem Witch Trials. Of the hundreds of women who were imprisoned, 36 women across America were accused of witchcraft and killed, and 20 of those executions took place in Salem. The committee printed a prospectus for the goals of the memorial and distributed it widely. They received 242 entries from around the world.

Parc de la Villette Competition, OMA

An international competition called for ideas to revitalize the 135-acre former site of the French national wholesale meat market and slaughterhouse as an urban park for the 21st century. OMA’s proposal for a park through “urban edge vitality” was an operational strategy in five parts to eventually generate a park. Parallel strips define programmatic areas of play and thematic gardens. A grid of points is overlaid to place small support structures. Circulation is defined through two major roads: a north–south axis and one that connects key programs. Large and unique objects are located in relation to sight lines. The design aims to disguise the intensity of the program and to allow for uncertainty as urban spatial needs change.

More than 470 entries were submitted to design what would become the largest park in Paris. OMA’s 1982 proposal critiqued the amount of program expected for the site as not leaving space for a park. In contrast, Bernard Tschumi’s proposal conceived of the park as a deconstructed building. Many believed that OMA’s scheme would be selected and lead to the firm’s first major built work. The split jury called for a second stage of competition and ultimately selected Tschumi.

High line Competition, TerraGRAM MVVA/DIRT Studio

In 2004, Friends of the High Line and the City of New York hosted an invited design competition to reimagine the abandoned 1.3-mile elevated rail line as a public space. TerraGRAM’s proposal celebrated the existing wildscape of the overgrown railway. In contrast to a cultivated, manicured, and static design, they promoted the High Line as a place where visitors could observe and engage with the ongoing transformation of the space through natural processes. New programs would be inserted, but would respect the existing vegetation with minimal disturbance. They wrote, “Succession is a matrix in form and time. Chance is the activating agent.”

From 52 teams, TerraGRAM’s proposal was one of four selected for exhibition. Though the proposal was not chosen to be realized, it continues to inspire designers to imagine process-guided landscapes informed by an “ecological logic.”

Pulse memoriAl Competition, CCxA and Studio Libeskind

The National Pulse Memorial and Museum in Orlando, Florida, intended to commemorate the victims of the 2016 shooting at Pulse nightclub, a hate crime resulting in 49 killed and 68 injured victims. A jury selected six finalists from 68 submissions. The CCxA/ Studio Libeskind team’s proposal is connected by a heart-shaped promenade of 366 rainbow gates (for each day of 2016). The promenade intersects intimate spaces of reflection, including a portion of the nightclub structure preserved as a space of sacred darkness. A museum tower west of the nightclub memorial site serves as a landmark with 49 columns of colored light activated by human touch. A survivors walk connects these memorials to sites of significance in the district and is marked by dawn redwoods arranged in clusters and loose groves to recall moments of solidarity and comfort.

The team’s proposal was short-listed but not selected. Ultimately, the designed memorial was not realized, as outrage from survivors and victims’ family members challenged the idea of the memorial as a tourist attraction. Temporary memorials remain.

Jennifer Birkeland is an assistant professor at Cornell University and a founding partner with op.Architecture + Landscape. Maggie Hansen is an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin.