Meet Michael Moynihan

Michael Moynihan is The University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture’s 2024-2026 Land, Space, and Identity in the Americas Fellow. Moynihan’s research focuses on the global history of housing during the Cold War/development era and broader questions about politics, technology, and expertise in architectural practice.

Before coming to Texas, Moynihan taught architectural history and theory at Cornell University and Syracuse University. His research has been supported by the Graham Foundation, the Canadian Centre for Architecture, the Society of Architectural Historians, the Andrew Mellon Foundation, and the Clarence Stein Institute for Urban and Landscape Studies. At Cornell, his dissertation was awarded a citation of special recognition for the Graham Foundation’s Carter Manny Award.

We recently caught up with Michael to learn more about him and his work.

Your research focuses on the global history of housing as well as politics, technology, and expertise in architectural practice. What drew you to focus on these topics professionally?

I see my role as a historian in a professional architecture school as someone who can encourage students to develop a geopolitically and environmentally conscious architectural practice. Housing is a great entry point for this because it shows how structural and economic forces are woven into design work. In my research and teaching, housing is a way to explore all sorts of important issues like nationalism, inequality, colonialism, migration, racial discrimination, imperialism, and environmental injustice.

Methodologically, housing and technology bridge two important scales in historical research. On one hand, you have large frameworks like modernization, economic development, and political systems—stuff that’s essential for understanding architecture. But these frameworks often have the tendency to reduce people to passive historical subjects and fail to account for how space is produced at a local, meaningful level. Housing offers a way to focus on the ways non-elites and everyday citizens shape the built environment. In my teaching, this research translates into discussions with students about broader understanding of transnational relationships in the Americas (particularly south-south collaborations) and how ideas and technologies change and adapt in different social and political contexts.

Tell us about your upcoming book, “Systems Will Prevail: Global Housing and the Decline of the Professional Architect.” What lessons from your research do you believe are most applicable to housing and the architectural practice of today?

The idea for this book, Systems Will Prevail, came out my dissertation research at Cornell University, which looked at an important moment in the 1970s for understanding how development policies would transform architectural practice and education in the second half of the 20th century. I looked specifically at the period after the oil crisis in 1973 and before the debt crisis in 1982, when a massive increase in transnational lending allowed international policymakers to recommend housing as a key tool for economic development and managing rural-urban migration. One might expect that architects would have played a central role in these projects and discussions, yet they were largely excluded. Paradoxically, what I found was that by the late 1970s, despite this new investment on housing at a global scale, a quarter of the world’s architects were unemployed. I argue, this massive unemployment signaled a larger decline in the profession because expertise in housing shifted away from architects and toward economists, consultants, and development experts who prioritized data analysis and economic growth over design.

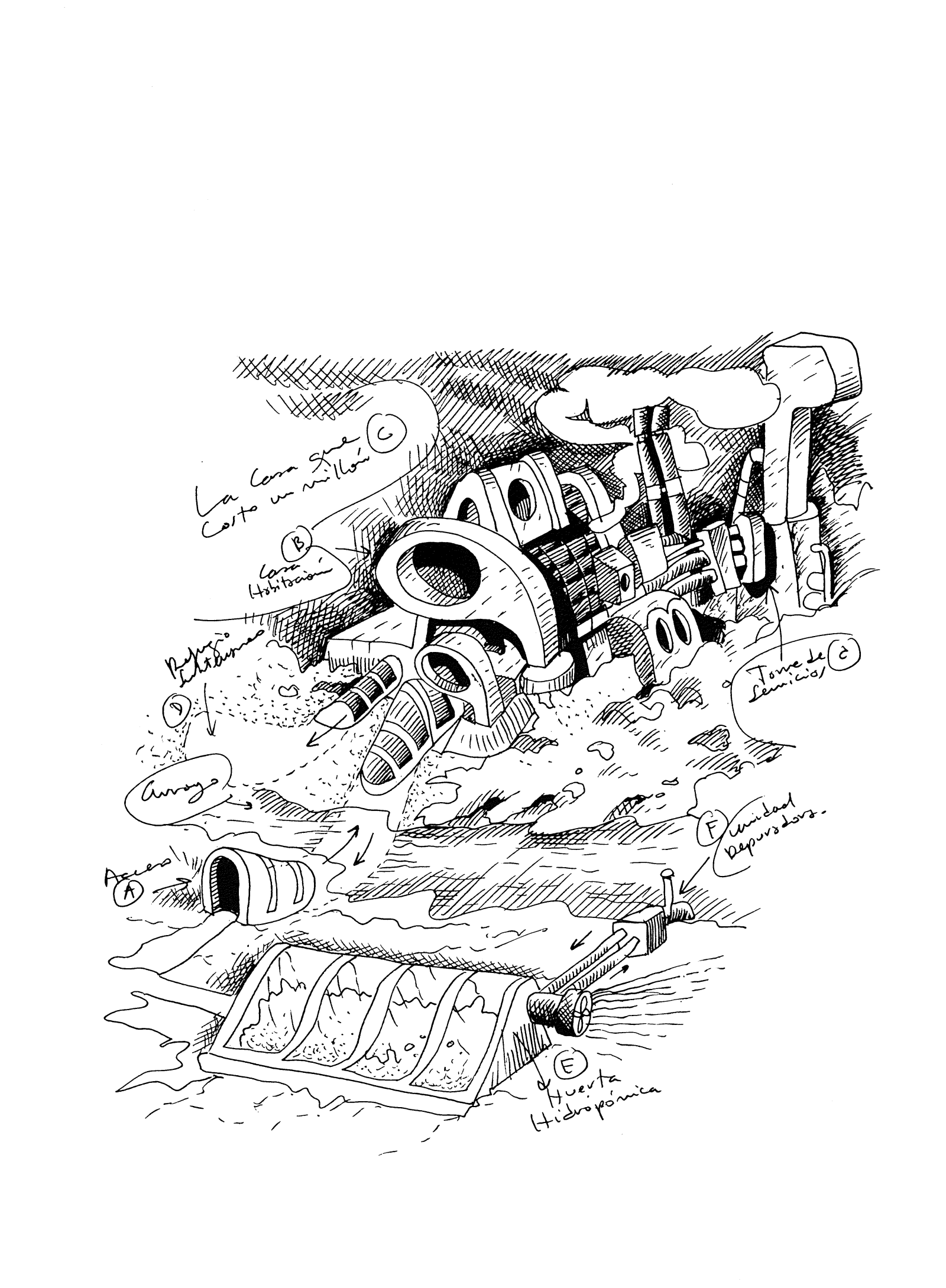

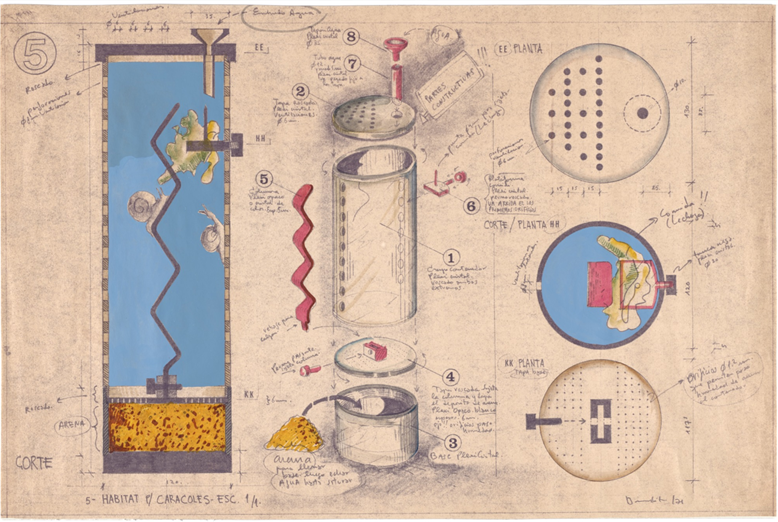

In the book project, instead of just telling a story about how architects were sidelined, I show examples of how some architects working in national housing ministries recognized this shift was happening and adapted by embracing data and information science. Through three interrelated examples, in Mexico, Argentina, and at UNESCO, I show how architects took on managerial roles and hired teams of sociologists, computer scientists, and data analysts to make the case for the importance of their own expertise. The book also highlights broader transformations in architectural practice and education, the growing influence of international organizations, and the emergence of data and information sciences as instruments of soft power in global development.

What about the UT School of Architecture, and the Architectural History Program, made you want to come to teach here?

UTSOA has a reputation for being one of the strongest history programs in the world. The history faculty here are exceptional, and, selfishly, I want to learn as much as possible from them. Of course, there is also a practical reason: UT has the best archives in the United States for Latin American Studies and a long-standing tradition of being the top school for studying architecture in the Americas. Throughout my career, most of the research paths I have pursued have led to documents held in UT’s collection, and now I have them at my fingertips. People often say this in a glib way, but it truly is an honor to be here, and I appreciate it every day.

What are you enjoying most about your time here so far?

The first thing I love about Austin is the food. My goodness—food trucks, dive bars, melted cheese—I’m in heaven! The second thing I love is the bike infrastructure. Although I don’t live close to campus, I ride my bike to work every day—it gives me time to think, and it’s great exercise. I just hope these two things find a way to balance each other out—right now, the BBQ and tacos are winning.

Besides your work, what is something you are passionate about, or what do you do for fun?

I grew up in the mountains in Colorado, so I really enjoy being outdoors—camping, hiking, and staying active. I’m also passionate about movies! When I was younger and had more free time, I made several short animated and stop-motion films. But now, I really enjoy watching movies, thinking about them, and discussing them. I live near WeLuvVideo, the lone surviving video rental store in North Loop. I like to randomly select films from different genres, most of which I’ve never heard of. Some are terrible, but it’s always interesting. I could (and sometimes do) do this every day. There are many similarities between movies and architecture: both offer a lens to discuss culture and politics, and how different representations of the world and aesthetic values change over time. I guess history is my passion.