"Green Infrastructure, Human Health, and Generative AI" by William C. Sullivan

On a hot July afternoon in Chicago, you can walk a few blocks and feel like you’ve changed cities. On one block (Figure 1), street trees throw deep shade over parked cars and cracked sidewalks. People linger on stoops. Kids ride bikes in the street. A neighbor pushes a stroller, chatting with a friend. Turn the corner, and the trees disappear. The pavement bakes, the air feels heavy and still, and people hurry as though the street itself were warning them away.

For decades, my colleagues and I have worked to understand why those two blocks feel so different. We have measured how everyday encounters with green spaces—street trees, pocket parks, community gardens, schoolyards—shape stress levels, attention, and social behavior. Across many cities, the studies reveal a clear pattern: people who live, work, or go to school in greener places report better mental health and recover from stress more quickly. Children and adults concentrate better and show fewer symptoms of attention deficit disorders. In neighborhoods with more trees and well‑designed parks, we see less aggression and violence, and in some studies, even fewer fatal police shootings. We have found that nature is not decoration; it is public health and safety infrastructure.

If we took these findings seriously, we would treat trees, parks, and other forms of urban nature the way we treat roads, sewers, and power lines. That, to me, is what “Landscape First” really means. When we invest in green infrastructure, we are not just making the city more beautiful. We are investing in the conditions that help people think clearly, manage stress, get along with one another, and, in many cases, stay alive.

Chicago offers both a hopeful and a sobering example. From the lakefront parks to the boulevard system and forest preserves, it is, on paper, a relatively green city. But canopy and park resources are not evenly distributed. Some neighborhoods enjoy generous tree cover and high‑quality parks; others have sparse canopy, little shade, and limited access to safe, well‑maintained open space. Residents feel the difference in their bodies and their daily routines: in summer heat, in chance encounters that build social ties, in the background level of tension on the street. The benefits of green infrastructure are real, but they are not yet shared fairly.

City officials know they ought to address these gaps. The trouble is that the most important benefits of green infrastructure are hard to see and hard to explain in budget hearings. It is straightforward to show how a new storm sewer will reduce flooding on certain blocks. It is much harder to argue that planting trees on those same blocks will reduce stress, lower rates of violence, and help children pay better attention in school. The evidence is there, but it sits in journal articles and technical reports. It rarely walks into the room where decisions are made.

At the same time, a new generation of tools—what we now call generative artificial intelligence—is moving into public life. Much of the conversation has framed AI as a way to cut costs or replace human labor. I think there is a better question for those of us who care about cities, health, and justice: how can these tools help us see the real value of landscapes, direct investments where they matter most, and bring more people, especially non‑experts, into the work of imagining and shaping their neighborhoods?

WHY THE BENEFITS STAY INVISIBLE

Despite strong evidence of positive results, landscape investment is often the first thing cut when budgets tighten. This is largely due to timing. A new park may, in fact, reduce assaults and improve school outcomes in the surrounding area, but those changes rarely show up in one neat line on a chart. They accumulate slowly, mixed with many other influences. Decision‑makers are left with a vague sense that “parks are good,” while a stack of spreadsheets urges them to focus on more conventional items.

A second reason for the broad lack of funding for landscape growth is inequity. The neighborhoods that most need the health and safety benefits of green infrastructure are often the ones with the least political power to demand them. In a city like Chicago, we can see on a map where heat, asthma, and violence are concentrated. We can also see where tree canopy and park acreage are thin. Turning those patterns into firm commitments—“we will invest here, for these reasons”—is still more guesswork than it should be.

A third challenge is that the planning process can feel opaque to stakeholders. Landscape architects, engineers, and planners are trained to read site plans and sections, to imagine three‑dimensional space from two‑dimensional drawings, while most residents are not. When communities are invited into the process, they are often asked to respond to sketches or diagrams that may not feel intuitive. Their insights about safety, comfort, and social life can be lost in translation.

These are the kinds of problems where generative AI can help—not by replacing human expertise or community voice, but by making evidence clearer and futures easier to picture.

HOW AI CAN HELP CITIES ACT MORE WISELY

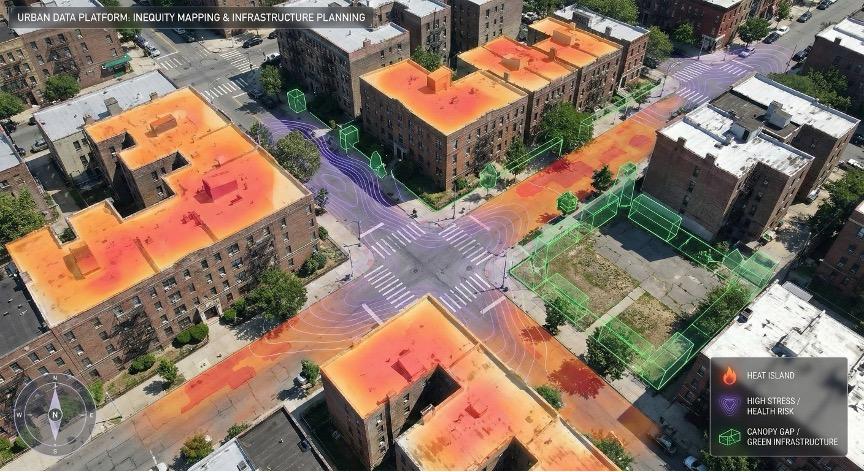

Cities face constant trade‑offs about how to spend limited funds. Generative AI can assist by pulling together what we already know. We have research on how green spaces influence health and behavior. We have data on heat, air quality, income, crime, school performance, and more. AI can integrate these threads of information and produce maps that illustrate and clearly communicate places where new trees or parks are most likely to produce multiple benefits at once (Figure 2).

Imagine a citywide map of Chicago layered with information: where summer temperatures run highest, where asthma and heat‑related illness are concentrated, where violent incidents occur, where tree canopy is thin, where incomes are lowest. None of this data is new, and AI does not discover a hidden law of nature—it simply synthesizes and depicts multiple layers of information in an accessible way. It turns scattered tables and reports into visuals that a mayor, a council member, or a neighborhood group can understand immediately.

When used well, this type of analysis does two things: it helps cities direct money toward the places where landscape investments will have the greatest impact, and it makes it harder to ignore historically neglected neighborhoods, because the inequities show up plainly on the screen.

SEEING POSSIBLE FUTURES TOGETHER

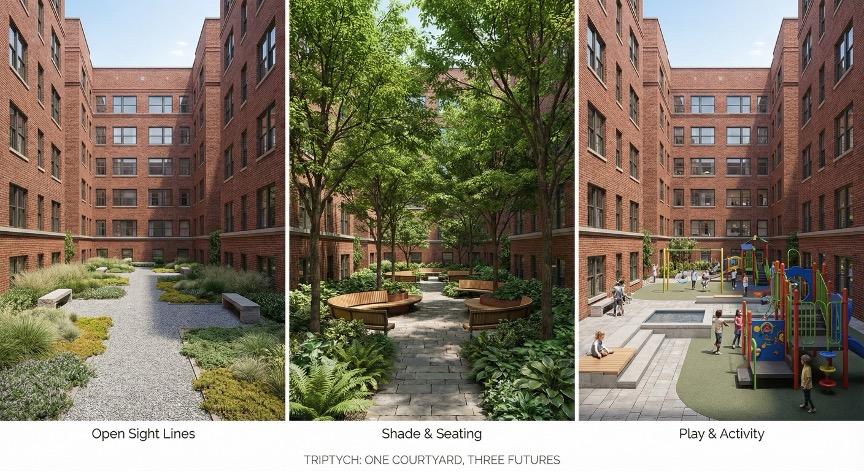

Even when we know where investments should go, we still must decide how those spaces should look and feel. That decision has enormous consequences for daily life: who lingers, who hurries through, who feels welcome, who feels watched.

Generative AI can now create realistic, editable images of streets, parks, and plazas. Tools such as OpenAI’s DALL·E or image generators built into systems like Gemini can take a photograph of an existing block and show that same place with mature street trees, a protected bike lane, or a small plaza and rain garden at the corner. With a few prompts, they can generate several plausible futures for the same site (Figure 3).

This has changed the way I think about public engagement. A parent in a disinvested Chicago neighborhood may not feel comfortable commenting on a plan‑view drawing of a schoolyard. Put a photo-realistic image on the table—“here is your school as it looks today; here it is with new trees and a shaded seating area; here it is with a fenced sports court and no trees”—and the conversation shifts. People know immediately what feels safe, what seems inviting, and what would work for their kids.

Because the images are editable, this is not a one‑shot exercise. Residents can say, “move that path,” “we need lighting here,” or “that bench should face the playground, not the parking lot,” and the AI can regenerate a new version in seconds. Instead of a few rounds of expensive renderings, you get an ongoing, visual dialogue among residents, designers, and planners.

Behind the scenes, these tools can also be guided by research. We know that clear sight lines, a variety of seating, and modest “soft edges” between public and private space are linked with more neighborly contact and lower aggression. AI systems can be trained to include these features in the scenarios they generate. They do not predict exactly what will happen, but they make it much easier to ask structured “what if” questions and refine designs before shovels hit the ground.

In short, AI can help people see and negotiate future landscapes together rather than asking them to trust abstractions.

LANDSCAPES THAT RESPOND IN REAL TIME

There is another frontier where AI and landscape meet: crisis response. As climate change brings more extreme heat, cities are looking for ways to protect residents on the hottest days, especially older adults, outdoor workers, and people without access to air conditioning.

Imagine combining generative AI with real‑time health information and environmental data. Public health departments already track heat‑related illness. Cities already collect temperature readings and, in some cases, data from street‑level sensors. Many people now wear devices that monitor heart rate, activity, and sometimes even physiological strain, and some are willing to share that information during heat emergencies for the sake of community safety.

AI can integrate these streams and produce hourly maps that show where people are most at risk: specific bus stops, playgrounds, sidewalks, or housing complexes. City staff could deploy temporary shade structures, misting stations, or cooling buses to those locations, not just to the city in general (Figure 4). Over time, the same data could guide where to plant large‑canopy trees, where to redesign plazas, and where to install permanent shade at transit stops.

The technology will not replace the need for long‑term investment in green infrastructure, but it can help make landscapes more responsive so that trees, parks, and shaded routes are part of city strategy to protect its residents during the most dangerous hours—not just pleasant amenities on mild days.

GUARDRAILS AND RESPONSIBILITIES

Whenever I talk about AI in urban design, people raise legitimate concerns. Data can be biased. Algorithms can be opaque. Visualizations can be used to justify decisions that are really driven by politics or profit.

These worries should shape how we use these tools. If the underlying data about crime or disorder reflects biased policing, an AI‑generated map might steer investments away from neighborhoods that already lack resources. If participation in wearable‑based heat studies is higher in affluent areas, responsive cooling strategies might over‑protect those communities and overlook others.

Thus, a few principles matter.

First, AI should extend, not replace, rigorous research and professional judgment. The most useful systems are grounded in well‑established evidence about how green spaces affect health, behavior, and safety. Their job is to apply that evidence at scale, not to spin up mysterious new claims.

Second, transparency is essential. Residents and decision‑makers should be able to ask: “What data went into this map? What assumptions shaped these scenarios? Whose experiences are missing?” If we cannot answer those questions, we should not rely on the output.

Third, participation is central. The same tools that generate maps and images for planning staff can and should be used in neighborhood meetings, classrooms, and advocacy campaigns. When AI makes it easier for people to see and debate possible futures for their own blocks, it is serving democracy rather than bypassing it.

LANDSCAPE FIRST IN AN AGE OF AI

If we return to that pair of Chicago blocks—the shaded, sociable street and the bare, tense one—the core message is straightforward. Urban nature changes how people feel and behave, day after day. It alters stress levels, attention, sense of safety, and willingness to look out for one another. That makes green infrastructure one of the most effective and humane investments a city can make.

Generative AI will not plant a single tree, but it can help us decide where trees, parks, and other green spaces will make the greatest difference. It can show us, vividly, what different design choices might mean for daily life; and it can invite far more people into the conversation about how their neighborhoods should look and feel.

For me, accessibility is the real opportunity. I reject AI as a replacement for human expertise or collective decision‑making, but I am optimistic about AI as a set of tools that help us see the power of landscape more clearly and advocate for it more persuasively. If we use these tools with care—guided by evidence and by the voices of the people who live in our cities—then “Landscape First” becomes a practical way to build healthier, safer, and more just communities.

William C. Sullivan (Ph.D., FASLA, FCELA) is a Professor of Landscape Architecture and Director of the Smart, Healthy Communities Initiative at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. For more than three decades, he has advanced the science of how urban green spaces shape mental health, attention, stress, learning, and social connection. Working with students and collaborators around the world, Sullivan’s teams measure both landscapes and people—linking tree canopy, vegetation, and everyday access to nature with changes in hormones, heart rate, brain activity, and psychological well-being. His research has influenced urban forestry, campus design, and city planning practice, providing clear evidence that thoughtfully designed landscapes can reduce inequities and improve life across the lifespan. Through this work, Sullivan has helped landscape architects, planners, and public officials make a stronger case for ambitious, health-supporting public spaces and investments in professional design.

Figures & Figure Prompts

The figures included in this essay were generated using Google's Gemini tool, Nano Banana. The exact prompts provided to Nano Banana for each figure are provided below.

A high-resolution, photorealistic split-screen comparison of a residential city streets in Chicago.

A high-angle, bird's-eye view of a dense urban neighborhood intersection, rendered in a photorealistic style with an Augmented Reality (AR) overlay.

The Base Layer: A typical city neighborhood with a mix of apartment buildings, cracked pavement, and sparse vegetation.

The Data Layers: Semi-transparent, glowing data visualizations are superimposed on the streets and buildings to reveal invisible metrics:

- Heat: Areas of asphalt and rooftops are highlighted in glowing gradient orange/red to indicate "heat islands."

- Health/Stress: Subtle, pulsing violet contours map areas of high physiological stress or health risk.

- Canopy Gaps: Bright green wireframe outlines show potential locations for new trees and parks where they are currently missing.

- Atmosphere: The image should look like a sophisticated, high-tech planning tool that makes invisible inequities "painfully visible" and actionable.

A wide, high-resolution architectural visualization split into three vertical panels (triptych). Each panel shows the exact same small, enclosed urban courtyard between brick apartment buildings, viewed from the same eye-level perspective, but with different design interventions:

A photorealistic, eye-level view of a sun-drenched city sidewalk during a heatwave, overlaid with a futuristic "Real-Time Response" user interface.

This article is part of a series of essays exploring topics inspired by “Landscape First” hosted at The University of Texas at Austin in the spring of 2025 with the generous support of the Still Water Foundation. All opinions, views, and provocations expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the official positions, policies, or perspectives of the School of Architecture.

READ THE ENTIRE LANDSCAPE FIRST ESSAY SERIES HERE →