"The Campus as a Landscape of Inspiration and Action" by Fritz Steiner

Let us begin with a city street in West Philadelphia in 1964 named “Locust.” By 1967, it had become Locust Walk at the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) after it was redesigned by landscape architect George Patten. Today, lined with magnificent trees, Locust Walk remains the central pedestrian spine of the Penn campus (Figures 1a, 1b, 1c). In addition to serving as a walkway, Locust also provides several other practical functions, such as offering a platform for student activities and facilitating deliveries. As its colors change with the seasons, Locust Walk becomes a beautiful respite.

During my time at the University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin), Penn’s Locust Walk served as my inspiration for a major transformation of another city street that bisected a campus. That project ultimately became Speedway Mall, a pedestrian-focused corridor redesigned by Peter Walker and Partners in 2018 (Figure 2). This example demonstrates how thoughtfully designed, inspiring landscapes can lead to transformative urban and campus design interventions.

After a brief introduction to the university campus as a distinct form of landscape practice—one with its own origins, typologies, and evolving cultural significance—I will highlight the influential contributions of Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., along with those of his two sons, John Charles Olmsted and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. In addition to their many designs and plans for college and universities, the senior Olmsted authored perhaps the first statement describing what a campus should be.

Next, I will examine the planning and landscape development of UT Austin and Penn, beginning in both cases with the work of the French American Beaux-Arts architect Paul Cret, whose designs helped define the spatial and architectural character of, especially, the UT Austin campus. I will conclude with an exploration of 21st-century sustainability innovations at both the UT Austin and Penn campuses, highlighting how these institutions continue to adapt historic landscapes to meet contemporary environmental aspirations.

THE CAMPUS IDEA

Thomas Jefferson’s public university for Virginia was devoted to educating leaders and is the principal origin of the American campus. Before Jefferson, the form of American institutions was largely influenced by Oxford and Cambridge, whose colleges were organized around one or more quadrangles or “quads.” These English schools were, in turn, modeled on the spatial organizations of those on the continent. The cloistered courtyard was used in Italy, Spain, and other parts of Europe during the Middle Ages.

Jefferson presented his plan to the University of Virginia’s governing board in May 1817. Instead of a church, a library was the architectural focus of Jefferson’s “Academical Village.” Inspired by Andrea Palladio’s drawings of the Pantheon in Rome, Jefferson called the library the “Rotunda.” Instead of a cloistered courtyard, its open space featured a generous “Lawn,” flanked by student and faculty housing, classrooms, and dining halls. Always interested in plants, Jefferson surrounded the core complex with gardens, enclosed by serpentine walls (Figure 3).

Jefferson presented a new physical model for higher education: the campus. According to Rybczynski (2026), “The term was derived from the Latin word for field, and its particular American meaning first appears in print in 1774 in reference to a playing field at the College of New Jersey [now Princeton University]. In time ‘campus’ came to refer to the entire complex of academic buildings and their grounds, replacing the earlier ‘yard’ (as in Harvard Yard), and giving rise to expressions such as ‘on campus’ and ‘off campus’.” (See also Turner 1984).

THE OLMSTEDS

Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. greatly advanced the concept of the college campus through his pioneering work in landscape architecture. The American campus largely emerged with the new field of landscape architecture in the late nineteenth century. While working for a mining company in California, Olmsted was invited in 1865 to prepare a plan for what would later become the University of California, Berkeley. UC Berkeley was established under the Morrill Land-Grant Act, signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln during the American Civil War (Steiner 2022). Justin Morrill of Vermont, the legislation’s sponsor, sought to promote scientifically grounded agriculture by establishing public colleges in each state.

Olmsted had long been interested in scientific agriculture, even before his design of Central Park, and was well acquainted with advocates, such as Morrill, who led the creation of colleges devoted to agriculture and the mechanic arts—what we now call engineering and applied sciences.

After returning east in 1866, Olmsted was offered another opportunity to contribute ideas for a land-grant institution, this time for what would become the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Although he was unable to realize his vision for the then-named Massachusetts Agricultural College, in December 1866, Olmsted revised, expanded, and published his Massachusetts report for a more general audience. Titled “A Few Things to be Thought of Before Proceeding to Plan Buildings for the National Agricultural Colleges,” his report became a model for the planning and design of future land-grant universities, leaving a lasting influence on the physical and philosophical development of the American campus.

Olmsted’s essay led to more campus design commissions. For instance, the trustees at the Maine Agricultural College invited Olmsted to the site of their new school, soon after his report was published. In the following year, he was retained by Cornell University. The senior Olmsted also worked for non-land-grant institutions, including American University, Bryn Mawr College, Fairleigh Dickinson University, Gallaudet University, Mount Holyoke College, Washington University, and, most famously, Stanford University (Figure 4).

Building upon their father’s earlier work at the University of Maine, the Olmsted Brothers continued his legacy in shaping the landscapes of land-grant universities across the United States. They also developed a comprehensive campus plan for Iowa State University, where Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. had once been offered the presidency (Steiner and Brooks 1986).

The Olmsted Brothers’ contributions extended to numerous other land-grant institutions, including Louisiana State University, Ohio State University, Oregon State University, the University of Florida, the University of Idaho, and the University of Rhode Island. They also prepared a campus plan for Alabama A&M University in Normal, one of the institutions established under the 1890 Morrill Act, which expanded the land-grant system to include historically Black colleges and universities. This second Morrill Act, also sponsored by Justin Morrill, provided federal support for schools in the South where Black students had been excluded from the original 1862 land-grant initiative.

Beyond the land-grant system, the Olmsted Brothers also designed campuses for several private and non-land-grant public colleges and universities, such as Fisk University—another historically Black institution—as well as Haverford College, Indiana University, Johns Hopkins University, Lafayette College, Oberlin College, and Williams College, among many others.

Through this vast body of campus planning and landscape design work, the Olmsted Brothers profoundly shaped the physical and philosophical concept of the American university campus, influencing both its aesthetic ideals and its functional relationship to the landscape across the United States.

WHO WAS PAUL PHILIPPE CRET?

Paul Cret was one of the most prominent architects in the United States from the first decade of the twentieth century through the 1930s. During the latter half of the twentieth century, his reputation waned with the rise of the International Style. The ex-pat Germans from the Bauhaus opposed the Beaux-Arts tradition, and Paul Cret bore the standard for the French school in America.

Cret first entered the École des Beaux-Arts in his home city of Lyon. In 1896, he won the Prix de Paris, enabling him to study at the most important architectural school in the world at the time: the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He came to the United States in 1903 to teach at Penn in its School of Fine Arts (McMichael 1983; see also Steiner 2011). Except for his service in the French army during the First World War, he lived in West Philadelphia until he died suddenly on a job site in 1945.

While teaching and directing the architecture atelier at Penn, Cret maintained a robust practice in Philadelphia, designing such buildings as the Pan American Union in Washington, D.C. (1907–1917), the Indianapolis Public Library (1917), the Detroit Institute of the Arts (1920–1927), and the Benjamin Franklin Bridge (1926) (McMichael 1983; Laird 1990; Grossman 1996). Cret and other Beaux-Arts architects influenced landscape design, which is evident in the work of the Olmsted Brothers (Olin 2026).

CRET'S PENN AND UT AUSTIN PLANS

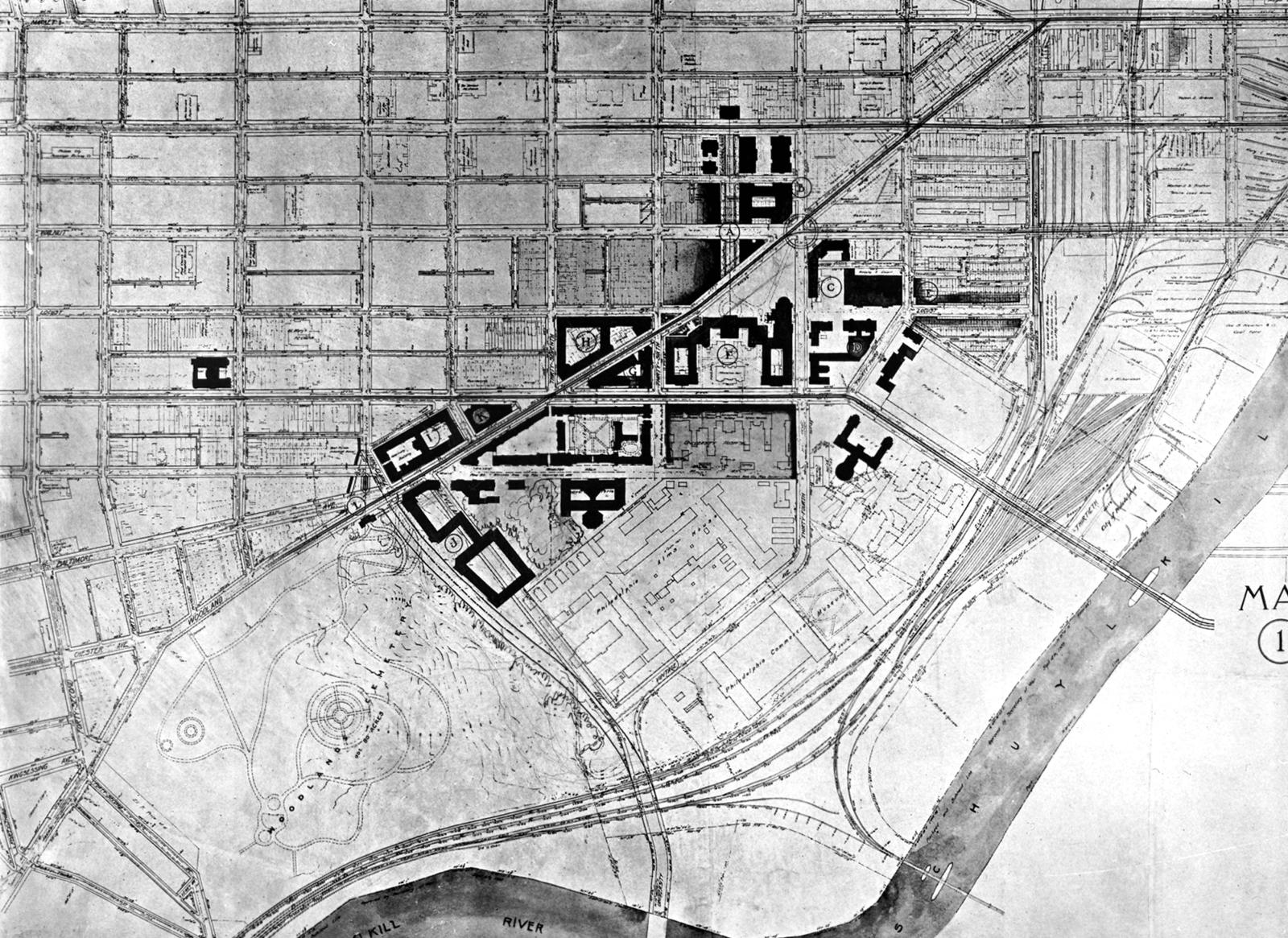

In 1913, Cret and Warren Laird prepared an expansion plan for Penn with their architecture students (Puckett and Lloyd 2015), which exhibited Cret’s growing interest in campus planning (Figure 5).

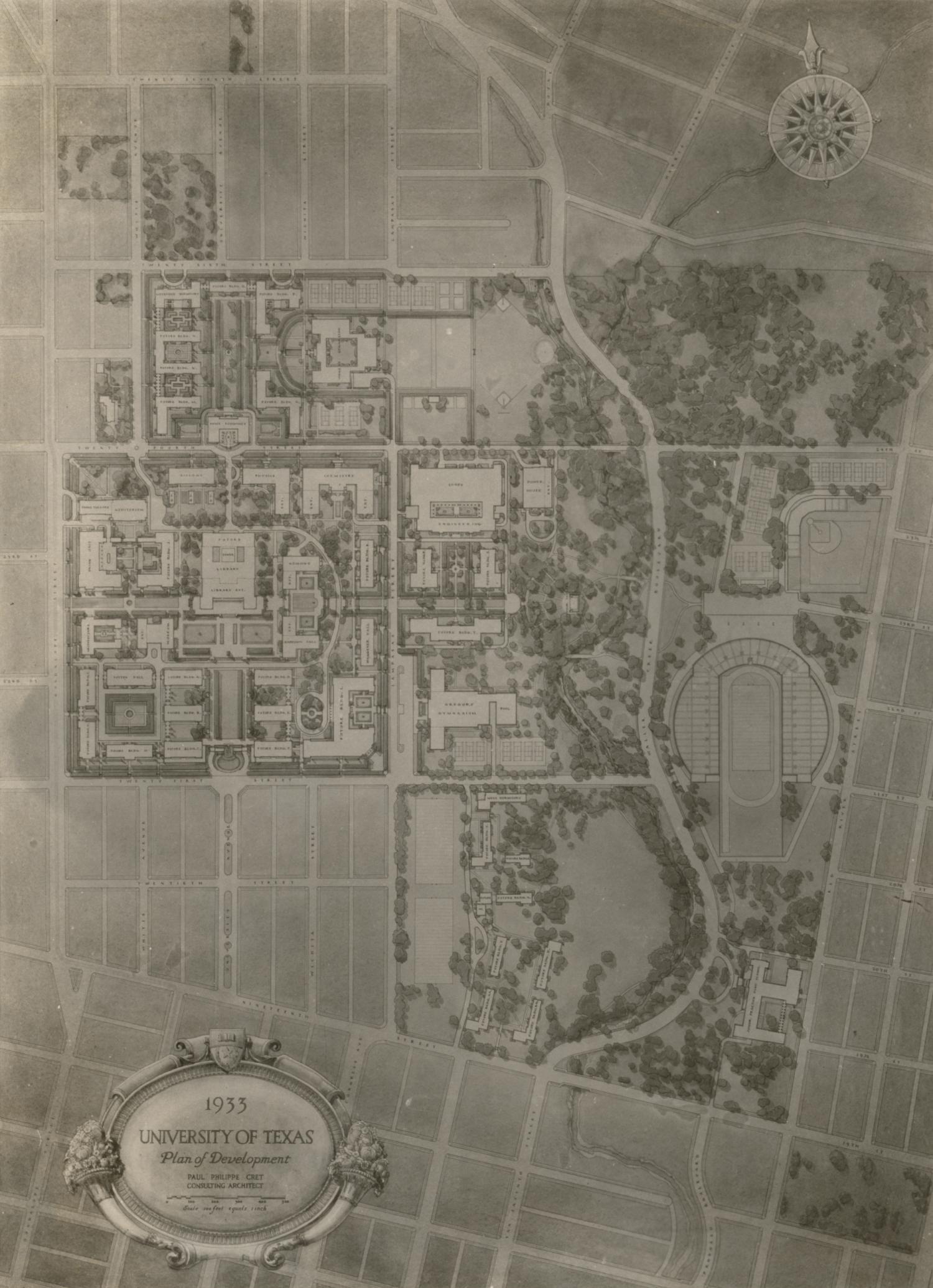

Cret’s 1933 University of Texas plan was undertaken at the height of his career (Steiner 2018). Cret worked with the Olmsted Brothers for the Penn plan and the Kansas City landscape architects Hare & Hare in Austin. Together, these collaborations illustrate how his Beaux-Arts sensibilities adapted to regional contexts, influencing the physical form of two of America’s most significant campuses.

Although Paul Cret taught at Penn, his campus-design influence at UT Austin proved far more lasting and significant (Figure 6). Penn was one of nine colonial colleges founded before the American Revolution and the first to achieve university status. It had moved to West Philadelphia in 1872 and needed better planning to fit in its then suburban location.

Cret’s 1913 plan for Penn proposed a broad, tree-lined green axis extending southward from the university’s main building, College Hall, as a unifying spatial element for the campus. Although this proposal was never realized in Philadelphia, Cret revisited and refined the concept two decades later in Austin, where it culminated in the design of the university’s Main and South Malls. The Main Mall and South Mall, the latter lined with magnificent live oaks, are oriented along a powerful north–south axis, extending from the university’s iconic hill-top Tower and Main Building toward the Texas State Capitol below. This composition created one of the most memorable and symbolically charged vistas in American campus design.

As I did in drawing inspiration from Locust Walk at Penn for Speedway Mall at UT Austin, Cret himself adapted and transformed an earlier Philadelphia idea into a new and distinctly Texan context.

AFTER CRET AND THE OLMSTEDS: FROM FORM MAKING TO SUSTAINABILITY

The Cret campus plan endured at UT Austin, but over time, design-led planning gradually gave way to administrative and bureaucratic decision-making (Speck and Cleary 2011). This trend began to reverse at the turn of the twenty-first century, first through the comprehensive campus planning efforts of architects César Pelli and Fred Clarke with the landscape architect Diana Balmori, and later through a series of influential plans prepared by the landscape architecture-led Sasaki Associates.

Meanwhile, at Penn, the campus expanded in tandem with the surrounding neighborhood of West Philadelphia, which had become urban. Although many distinguished architects contributed new buildings over the decades, the campus as a whole lacked a cohesive landscape identity—Locust Walk being the most notable exception.

This changed in 1977, when Dean Sir Peter Shepheard and several faculty members from Penn’s Department of Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning prepared a landscape framework plan (Steiner and Bunster-Ossa 2026) (Figure 7). This intervention transformed the campus character, establishing a unified and pedestrian-friendly landscape structure. Subsequent master plans by OLIN and Sasaki Associates built upon this foundation, ensuring the continual renewal and stewardship of Penn’s historic and contemporary landscapes.

Today, both Penn and UT Austin stand at the forefront of sustainable campus design, exemplified by their early engagement with the SITES landscape rating system, developed to advance best practices in ecological and resilient design and administered by Green Business Certification Inc. At Penn, Shoemaker Green achieved SITES certification, while at UT Austin, the Dell Medical School District was similarly recognized, demonstrating each university’s ongoing commitment to integrating sustainability into the evolution of their historic campuses (Steiner 2025).

One of the plans Sasaki developed for UT Austin was for its new medical school. The Dell Medical District was an early project (completed in 2017) to receive SITES certification. The plan focused on restoring a degraded creek, planting native vegetation, and improving stormwater management. The new medical school administration sought to extend its commitment to health into the surrounding landscape (Figure 8).

The 6.5-hectare (16.2-acre) medical district lies in central Austin, along the southern edge of the Texas campus. The previously neglected Waller Creek was transformed into a valuable campus asset. This restoration involved removing invasive species, stabilizing stream banks, and re-vegetating with native plants. Additional features included rain gardens, the preservation of mature live oaks, and soil remediation. The result is a landscape that fosters social interaction and enhances ecosystem services through thoughtful design.

Penn also undertook an early SITES-certified project aimed at advancing ecosystem services. Shoemaker Green, covering about 1.2 hectares (3 acres), is located adjacent to the university’s major athletic venues. Landscape architects Andropogon Associates transformed aging tennis courts into a vibrant new open space. José Almiñana of Andropogon, one of the original creators of the SITES rating system, used Shoemaker Green to demonstrate its potential (Figure 9).

Completed in 2012, the project has proven highly effective in managing stormwater and mitigating urban heat island effects, while also providing memorable spaces for social gathering. A large rain garden with native vegetation manages, filters, stores, and transpires rainwater. Water collected from nearby buildings and surfaces infiltrates the soil, reducing runoff and improving water quality. Shoemaker Green offers ecological value and aesthetic appeal, serving both people and wildlife.

PROSPECTS

Landscape architecture and the American university campus have evolved in tandem. While other disciplines—most notably architecture, engineering, horticulture, and botany—have made important contributions, landscape architecture has played a uniquely integrative role. University administrators and major donors have also had significant, mostly positive, influence; however, when political interests enter the process, the outcomes are usually less beneficial.

Landscape architects shape and sustain the living fabric that binds the campus together. Without their guidance and vision, that fabric can become fragmented or neglected. The campus landscape, in turn, provides a unified setting and a lasting sense of place for all who study, work, or visit. It functions not only as a physical environment but also as a living expression of the university’s identity, history, and aspirations.

Frederick “Fritz” Steiner (Ph.D., FASLA, FCELA, FAAR) is dean and Paley Professor at the University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of Design, and faculty co-director of The Ian L. McHarg Center for Urbanism and Ecology.

Previously, he served as dean of the School of Architecture and Henry M. Rockwell Chair in Architecture at The University of Texas at Austin for 15 years. He has taught at Penn and the following institutions: Arizona State University, Washington State University, the University of Colorado at Denver. He was a visiting professor of landscape architecture at Tsinghua University in Beijing, China. Dean Steiner was a Fulbright-Hays scholar at Wageningen University, The Netherlands and a Rome Prize Fellow in Historic Preservation at the American Academy in Rome. During 2013-2014, he was the William A. Bernoudy Architect in Residence at the American Academy in Rome. He is a Fellow of both the American Society of Landscape Architects and the Council of Educators in Landscape Architecture, and a Scholar at the Penn Institute for Urban Research. Steiner helped establish the Sustainable SITES Initiative, the first program of its kind to offer a systematic, comprehensive rating system designed to define sustainable land development and management and holds the SITES Professional (SITES AP) credential. In 2019, he co-founded The Ian L. McHarg Center for Urbanism and Ecology with the late Richard Weller.

Steiner has written, edited, or co-edited 22 books, including Penn’s Sylvania: The Campus as Landscape (2026) with Ignacio Bunster-Ossa; Megaregions and America’s Future (2022), with Robert Yaro and Ming Zhang; Design with Nature Now (2019), co-edited with Richard Weller, Karen M’Closkey, and Billy Fleming; and Making Plans: How to Engage with Landscape, Design, and the Urban Environment (2018); and Nature and Cities (2016), co-edited with George Thompson and Armando Carbonell.

Steiner was a presidential appointee to the national board of the American Institute of Architects and was on the Urban Committee of the National Park System Advisory Board. Previously he served as president of the Hill Country Conservancy (an Austin land trust) as well as in various capacities on the boards of Envision Central Texas and the Landscape Architecture Foundation. He worked on the Austin Comprehensive Plan (Imagine Austin) and on the campus plan for The University of Texas at Austin.

Steiner earned a Master of Community Planning and a BS in Design from the University of Cincinnati, and his PhD and MA in city and regional planning and a Master of Regional Planning from the University of Pennsylvania. He received an honorary MPhil in Human Ecology from the College of the Atlantic, and in 2023, the University of Cincinnati honored him with the UC College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning Outstanding Alumni Award.

Works Cited

This article is part of a series of essays exploring topics inspired by “Landscape First” hosted at The University of Texas at Austin in the spring of 2025 with the generous support of the Still Water Foundation. All opinions, views, and provocations expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the official positions, policies, or perspectives of the School of Architecture.

READ THE ENTIRE LANDSCAPE FIRST ESSAY SERIES HERE →