History of the Colorful Mural in Goldsmith Hall

Anyone who has visited Goldsmith Hall in the last few decades has likely seen the mural on display in the lobby of the Dean’s Suite. What you probably don’t know is that the commanding 8 x 16-foot piece was designed by the renowned architect and educator Michael Graves.

Graves first came to The University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture in the spring of 1974 as part of an experimental architectural design class. Over the semester, four different visiting professors were invited to campus to teach one class of students for approximately one month in rotation to expose them to differing architectural perspectives. Graves was the first to visit that semester, followed by the architect and design theorist Louis Sauer.

As an architect, Graves first achieved notoriety in the late 1960s as a member of the New York Five, an informal group of young architects who helped redefine modernism. In the late 1970s, Graves shifted away from modernism to pursue Postmodernism and New Urbanism design for the remainder of his career. Graves became one of the most celebrated postmodernists in the 1980s, designing such seminal postmodern buildings as the Portland Building in Portland, Oregon, and the Humana Building in Louisville, Kentucky.

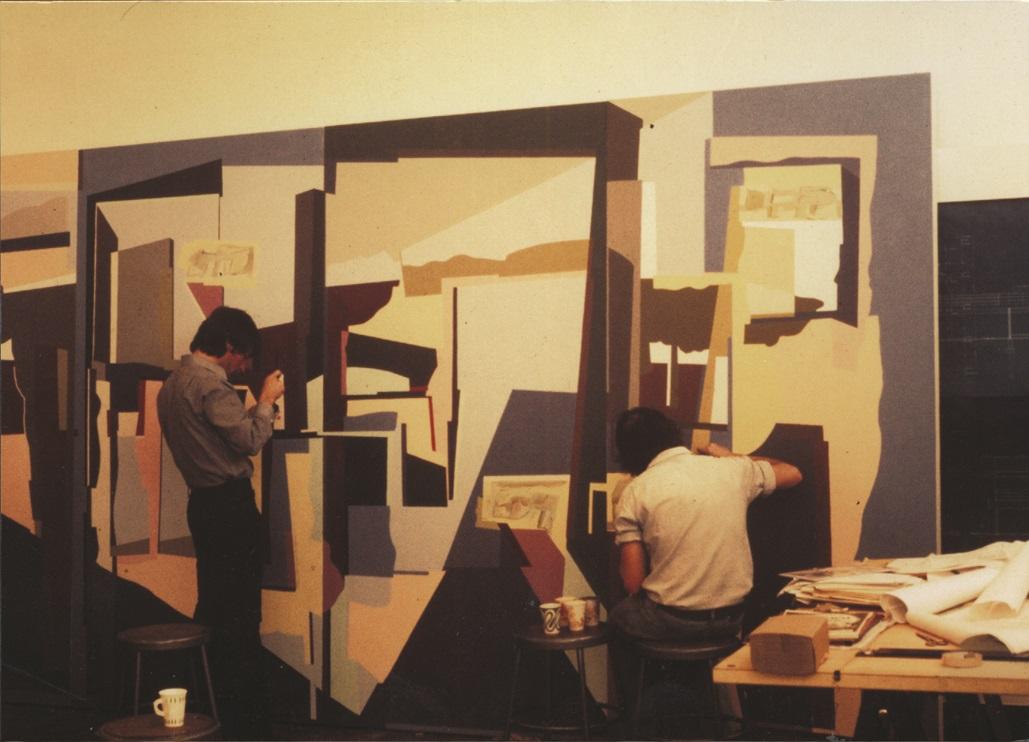

These projects exemplify the values of postmodernism—rich, saturated colors and abstractions of distinctive elements from classical architecture. While at The University of Texas at Austin, Graves shared these emerging architectural values with the twenty students in his class via their work together and his design for the 8 x 16-foot cubist-inspired mural. According to a 1974 article in The Daily Texan, the vibrantly colored piece “incorporates [Graves’] concepts on space and architecture” and was designed by Graves during the first three weeks of his time on campus. From there, students painted the piece under his direction for the remainder of the visit.

The mural was originally displayed in the jury room during the spring 1974 semester, then exhibited in museums throughout the state—eventually returning to Goldsmith Hall, where it has lived ever since.

Reflecting on the importance of drawing to architectural practice in a 2012 opinion piece for the New York Times, Graves noted: “Architecture cannot divorce itself from drawing, no matter how impressive the technology gets. Drawings are not just end products: they are part of the thought process of architectural design. Drawings express the interaction of our minds, eyes, and hands…Our physical and mental interactions with drawings are formative acts. In a handmade drawing, whether on an electronic tablet or on paper, there are intonations, traces of intentions, and speculation. This is not unlike the way a musician might intone a note or how a riff in jazz would be understood subliminally and put a smile on your face.”

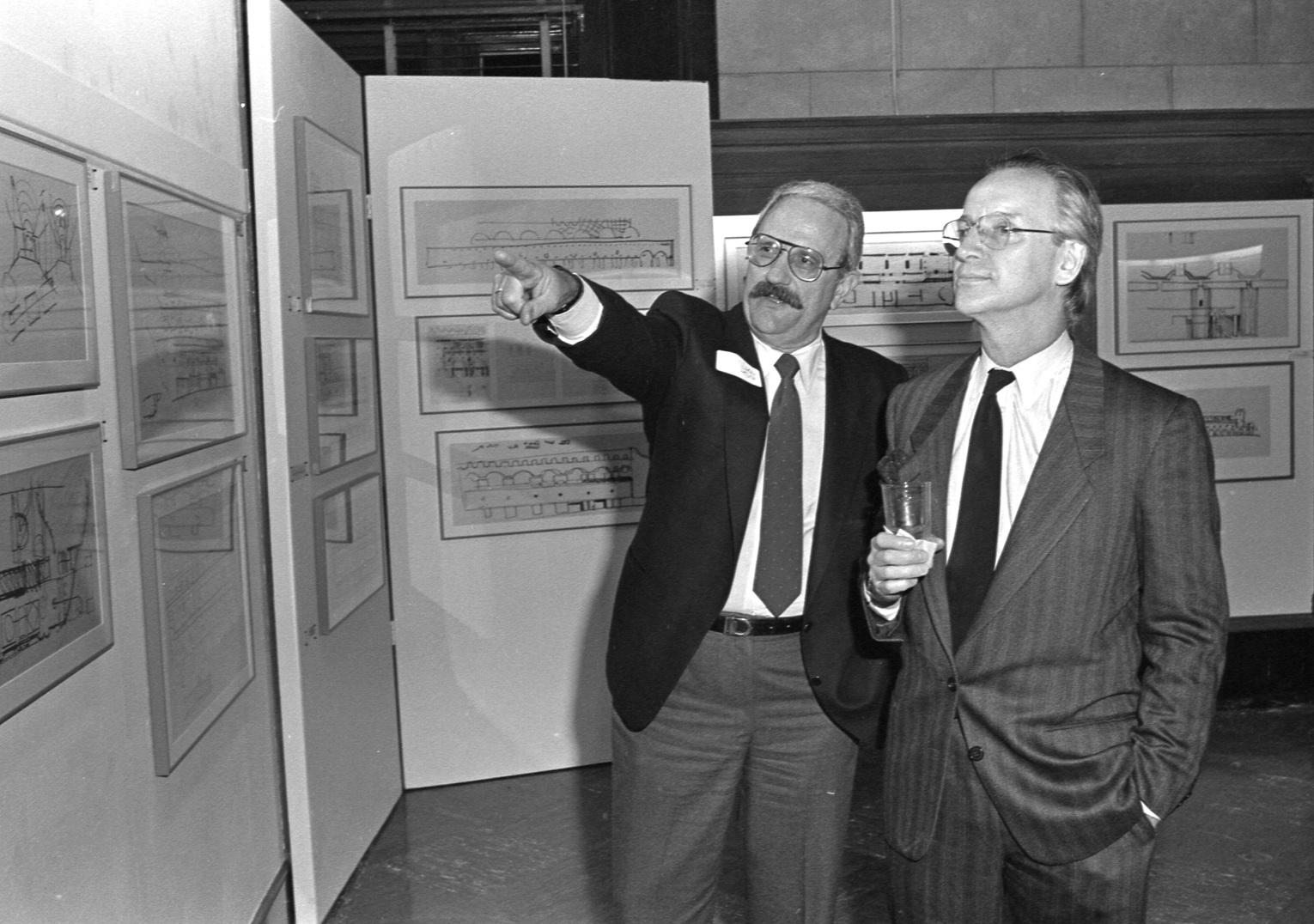

School of Architecture Professor Vince Snyder was personally and professionally close to Graves, who was Snyder’s professor, mentor and dear friend. Looking back on Graves’ work and the Goldsmith painting, Snyder notes:

“Indeed, the painting represents a critical time in architecture and many related design fields at the cusp of an entirely new era. As evidenced in the painting, Graves’ work always incorporated humanism through color and allegory—even as a celebrated modernist—although largely through Cubist techniques during that time. Later, within his own development of postmodern historicism, he became more literal. However, it is also crucial to point out, he was not a copyist. He always transformed any referential material, modern or classical, into unique designs that reflected salient aspects of contemporary society. We are very fortunate to have such a work accessible to everyone at the school.”

In addition to the Portland and Humana Buildings, Graves designed more than 350 buildings throughout his career, including such prominent projects as the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport in The Hague, an expansion of the Denver Public Library, numerous commissions for Disney, and the scaffolding design for the 2000 Washington Monument restoration. Graves’ distinctive architectural designs also afforded him the opportunity to work as a designer in other fields, including product design for everyday objects like tea kettles or spatulas for Target, Alessi, JCPenney, and others. After becoming paralyzed in 2003, Graves became interested in healthcare design—designing items like a wheelchair, heating pads, and bathroom handrails.

Stop by the Dean’s Suite to see the mural yourself and learn more about Graves’ career and work here.