Reflections on “Eco Illusions: The Plastic Behind the Green” Exhibition—an Interview with Professor Danelle Briscoe

Associate Professor Danelle Briscoe partnered with the Materials Lab director Jen Wong to present the exhibition "Eco Illusions: The Plastic Behind the Green." On view at the Materials Lab through the fall semester, this showcase prompts the question: can we truly call a system 'green' if it’s propped up by materials that may outlive the ecosystems they aim to sustain? Briscoe invites visitors to confront these contradictions with curiosity and critical thought, encouraging a deeper conversation about the future of design, materials, and ecological responsibility beyond aesthetics.

Architecture as a constructive practice requires broad knowledge of materials and their respective life cycles, and it is fortunate that there is growing focus on resilience and symbiotic design with natural world. Still, contemporary design pedagogy requires extensive iteration of models that often end up in landfills. Briscoe urges us to embrace new methodologies and mediums for design and building, tackling these contradictions as opportunities for innovative alternatives beyond surface appeal rather than conceding to environmentally harmful materials and systems as necessary evils.

Danelle Briscoe offers us new insight into her approach of this tactile exhibition at The Materials Lab and the realities of the challenges of “sustainable design” in a recent Q&A:

How can aesthetics of “greenness” in spatial design both help and harm efforts for sustainable building practices?

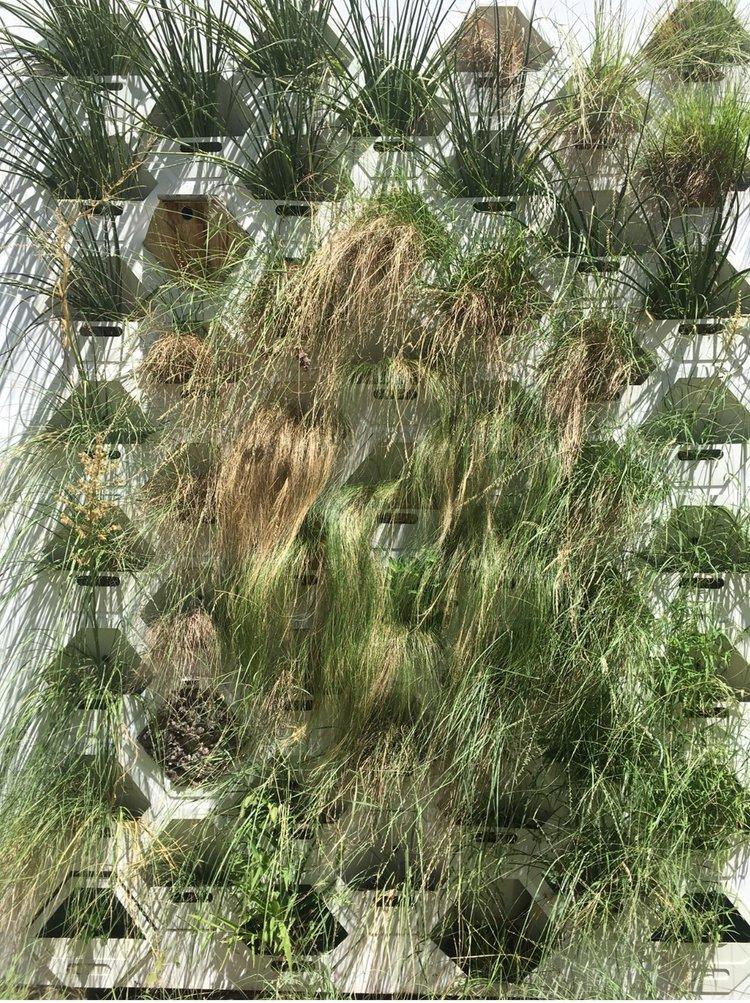

Superficiality is extremely detrimental to resilient design, and oftentimes what claims to be “green design” is essentially wallpaper with plants on it. As a field, we’re not being as responsible as we should to push these ideas further. The desired look-and-feel of a design often masks a fraught system comprised of plastic materials, and there is a general lack of understanding of the involvement and mechanisms that it takes to create something like a living wall and ensure it survives. Plastic has done great things, but the truth is that those plastic systems will outlive the plans that they’re trying to hold up.

That said, more people are becoming aware of resilient design methods, even if it’s not their research direction. While a student can only go so far with the amount of time and resources they have, they do know that a living wall system is not going to be two inches thick and that post-construction maintenance must be considered. This fourth dimension is often overlooked when we create buildings. Landscape architecture considers this more often, since these designers must make sure their plants are growing and viable, but in architecture, there is naive thinking that we can set it and forget it. A turnkey expectation is the root of many problems in resilient design, especially when renderings are the primary tools of communicating to clients. Students must think of the consequences and gravity of their selected systems and materials—a 1:1 scale is important, and that is what "Eco Illusions: The Plastic Behind the Green” aims to offer.

What materials and systems are you most excited to showcase in this exhibition?

Foam is one of the most toxic materials used in architectural modeling, so I was particularly interested in featuring and utilizing Cruz Foam—a domestically sourced industrially compostable material made of upcycled food industry waste. Performing as the “soil” in the exhibition’s planters, this material is an excellent alternative to typical EPS blue foam: it cuts cleanly and easily, works with biodegradable hot glue, and smells like marshmallows when cut with the hot wire cutter. I was able to explore the potential of Cruz Foam as an architectural design material through the support of a studio grant provided by the Materials Lab, and it’s been exciting to see students embrace it as an alternative (especially when you can avoid the headaches caused by toxic EPS foam). It was especially fun to think of this as a component of the exhibition display, where all of the representations of plant and soil are compostable.

Bee brick is also really exciting. It fits into a wall like any other brick would. It provides habitat for bees without requiring any additional technological layers, so it feels simple and adaptable.

How are UT students shaping future experimentation through research and development?

Beyond their willingness to experiment with new materials, students are instrumental participants in shaping the discourse of future habitat design. It is exciting to hear how students imagine what living systems in the built environment can be, especially when multiple disciplines of interiors, landscape, and architecture are at the table.

When prompted, students weren’t necessarily convinced that providing habitat for the “other” (bees, pollinators, birds) should encroach into our personal spaces as humans. It became clear that this is a very complex question with varying ranges of comfort—some embraced it, but others didn’t understand why we wanted to have bugs around our workplaces or homes. Design fields’ mentality of perfection in representation doesn’t allow for anything to be dirty or outside of our comfort zone, and I began to question the idealism of these proposed hybrid spaces. Their critique was meaningful, and it has prompted me to be true to both sides in my research.

It’s also great that in a decade from when the Living Wall pilot project was implemented on the west facade of Goldsmith, almost every studio has a student interested in this direction. I’ve seen other professors take on this direction, too, so it's reassuring that people are treating living walls as a design direction that is positive and not an obligation. They’ve seen examples in the world, if not locally, and that is very meaningful.

Which organizations or project examples should we look to for guidance in responsible infrastructure for green installations?

The first project that comes to mind is outside of the scale that we normally operate in: the Great Green Wall initiative, spanning 22 countries in Africa. We are used to thinking of living systems as a single interior or exterior application, but this project is continental in scale.

During a fellowship in Spain from 2016-2018, I was able to explore some of the most cutting-edge research and development on living walls. In Madrid, CaixaForum, an old power station transformed into a cultural center designed by Herzog & de Meuron, boasts a visually stunning example of an exterior vertical garden wall system developed with botanist Patrick Blanc. However, since it requires a massive amount of water, it varies in its growth health. Sometimes it’s dry, and other times it’s flourishing. A better application is Capella Garcia Arquitectura’s Jardí Tarradellas on a residential apartment block in Barcelona. This one has no plastic and is built of an extremely light metal cage system that holds the garden while allowing air, water, light, and life forms to permeate the structure. The project is meant to be an evergreen corner of pollination for insects and a bustling habitat for birds. It seems to survive on its own—the plants are doing exactly what they need to be doing. It's clear that the design team was very thoughtful about post-construction maintenance. It was wonderful to experience a vertical garden that performed beyond just a plaque: the space invites visitor participation to identify species throughout the year, so it is truly a communally-stewarded space.

I have also enjoyed many conversations with Stefano Boeri of Stefano Boeri Architetti. His firm, in my mind, is leading the way with Living Wall systems becoming a reality in architecture.

"Eco Illusions: The Plastic Behind the Green" is an extension of the UTSOA Living Wall Research and Project at the western facade of Goldsmith Hall directed by Associate Professor Danelle Briscoe in collaboration with the late Dr. Mark Simmons, Director of the Ecosystem Design Group at the University of Texas at Austin Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. This pilot was established in 2015 as a pioneering exploration of sustainable design, blending architecture, ecology, and innovation.