"Fight or Flight: Space Colonization and the Future of Landscape Architecture" by Ignacio Bunster-Ossa

If a SWOT analysis were conducted on human society today, Strengths, Weakness and Opportunities would be overwhelmed by perceived Threats with climate change and AI at the top of the list, closely followed by space colonization. The goal of this essay is to address these threats while attempting to clarify what matters most and why.

To start, the most urgent threat to discuss is climate change. The world is on track to surpass the 1.5o centigrade atmospheric warming threshold outlined in the Paris Agreement within three–to–five years, and some estimates predict a 3o global temperature increase before the end of the century. My grandchildren are likely to experience permanent coastal inundations, more frequent and damaging storms, recurrent and more prolonged heat waves, sustained droughts and wildfires, and higher exposure to disease vectors. To these effects must be added food supply disruptions and costly infrastructure repairs. Poor communities will wither; rich communities will hail resilience.

Secondly, the intellectual, biological, and material consequences of AI have begun, looming darkly in our daily lives and in our collective imagination. In Ray Kurzweil’s futurist nonfiction The Singularity is Nearer: When we Merge with AI, the author posits cataclysmic impacts from the deployment of AI-facilitated nanotechnologies in the form of “Gray-goo,” the notion of “self-replicating machines that consume carbon-based matter and turn it into more self-replicating machines, causing a chain reaction that could potentially turn the entire biomass of Earth into such machines”. 1 In this nightmarish and perhaps not-so-distant future of AI-generated biotechnology, there is added peril of these cellular machines going rogue and generating new virus strains. In present day, we are witnessing the impacts of AI in milder but still menacing ways: the realignment of the labor force and erosion of education at large. Need to take a language elective? No need, just put on Apple earbuds with instantaneous translation. Goodbye, foreign language teachers.

Lastly, we must critically understand the desire for space colonization held by the earth’s most affluent humans. Elon Musk has set his sights on Mars. Humanity must become a space-faring civilization, as a “life insurance for life collectively,” he believes.1 He sees the Sun eons from now getting brighter and hotter, burning the atmosphere, and boiling the oceans—climate change in extremis. He also sees space colonization as insurance from home grown threats, such as nuclear annihilation. Jeff Bezos is equally enthusiastic about space, albeit for different reasons. Instead of terraforming other planets, Bezos envisions an orbital world populated by billions, supported by a moon and asteroid-based extraction economy. Doing so, he believes, would spare humanity the torment of living on an afflicted planet with ever diminishing resources.2

The good news is that, historically, every juncture portending doom has begotten a countervailing force. In 1942, Isaac Asimov offered a set of “AI” safeguards known as the Three Laws of Robotics (appearing in the short story, Runaround): 3

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey the orders given to it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence, as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.

More recently in 2017, the Future of Life Institute held a conference at the Asilomar Conference Center in Monterrey, California, to discuss the benefits of AI. Participating scientists, economists, philosophers, and industry leaders (Elon Musk among them) drafted 23 principles to guide the development of AI. 4 First on the list was this: “The goal of AI research should be to create not undirected intelligence, but beneficial intelligence.” Another one states that “If an AI system causes harm, it should be possible to ascertain why.” The last one states that “Advanced AI could represent a profound change in the history of life on Earth and should be planned for and managed with commensurate care and resources,” referring, presumably, to the immense consumption of energy, water and rare earths required to build and operate AI data centers. 5

From a climate standpoint, a significant countervailing force can be attributed to Alexander von Humboldt. He is arguably the first scientist to note the impact of human action on climate, specifically how deforestation alters temperature, affects water supply, and abets flooding. But Humboldt did more than usher in concerns about human action upon the environment—he noted nature’s inherent aesthetic appeal.6 After arriving in Venezuela in 1799, he wrote:

“What trees! Coconut palms, 50 to 60 feet high; Poinciana pulcherrima, with a big bouquet of wonderful crimson flowers; pisang [banana tree] and a whole host of trees with enormous leaves and sweet-smelling flowers as big as your hand. As for the colours of birds and fishes—even the crabs are sky-blue and yellow!”

Humboldt effectively released nature from its utilitarian prison by recognizing the power of biophilia two centuries before E.O. Wilson popularized the term.

Humboldt’s wide-eyed capture of colorful crabs (they were crayfish) occurred a few years after two people for the first time stepped into a hot-air balloon near Paris and rose, untethered, hundreds of feet before an amazed crowd. Escaping gravity (Flight), and marveling at and seeking to protect the Earth’s biota (Fight) have marched in lockstep opposition ever since. An extraordinary synchronicity occurred in the late summer and early fall of 1962. On September 12, in a speech at Rice University, John F. Kennedy committed to having a man set foot on the moon and bringing him back alive within a decade. On the 23rd day of the same month, The Jetson’s animated TV program aired its first episode, fanning the fantasy of a high-tech life aloft with flying cars and robotic servants. On the “Fight” side, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring was published four days after The Jetson’s television appearance. A week later, the World Wildlife Fund, an organization devoted to conserving the most vital natural places on Earth, opened its first office, in Morges, Switzerland. By all indications, “Flight” is well ahead in the race. Every 38 hours on average, a rocket shoots into space from somewhere around the globe.7 In contrast, more than 600 square miles of forests are lost annually.8

It may seem odd to pair space colonization with climate change and AI as a convulsing agent, but of the three spokes of the wheel of doom, I find it to be the most harmful. Common to both space industry juggernauts is the vision of space as a survival antidote, a form of life-saving vaccine with rockets acting as the proverbial syringe. But this is a chimera, and it engenders a false and damning sense of security about our place on the universe—and on Earth. As explained by physicists John D. Barrow and Frank Tipler in The Anthropic Cosmological Principle (1986), there are evolutionary forces at work superseding humanity’s spacefaring impulse.9 Their argument, supplemented by other sources, is this:

- Evolution never goes backwards, i.e., humans will never evolve to become fish.

- The Universe (as understood by the laws of physics) is designed to permit the creation and evolution of life. If it were otherwise, we would not exist.

- The purpose of life is for the Universe to be observed and understood.

- What, then, is life? It is, since the onset of DNA, information processing.

From these points we can conclude: 1) the human brain evolved specifically to advance an understanding of the Universe (if it were otherwise, we would still be adhering to a pre-Ptolemaic view of Earth); and 2) a species with higher information processing power can be expected to emerge to further advance such understanding. Ancient civilizations used mechanical devices, such as the Greek Antikythera from the first century BCE, to calculate astronomical positions, eclipses, and calendar cycles, and humanity has since relentlessly sought higher computational power. Today, AI surpasses the capability of human brain through machine learning and generative algorithms (e.g.: IBM’s Watson). Physical robots can already reason and act autonomously toward defined outcomes (e.g.: Google’s Gemini Robotics). Self-replicating robots—called Von Neumann Probes after the celebrated 20th century mathematician’s vision of self-reproducing machines scanning the far reaches of the solar systems for minerals—cannot be far behind. Space-faring robots such as the AI-equipped Mars Rovers are credible progenitors of such self-replicating “organisms.” With AI, we have, in effect, began the next step in the evolutionary ladder. This may be a sobering conclusion, but it makes total anthropic sense. To further explore and understand the Universe, organisms capable of withstanding eons in the vacuum of space are a necessity. The human body and psyche are not remotely capable of meeting such a demand; Von Neumann Probes will be, as Barrow and Tipler argue in The Anthropic Cosmological Principle. AI may pose evolutionary pains for humanity, but fear not: its mission is ultimately not Earth-bound.

We may one day see people living in orbit, on the moon, or even on Mars, but they will be a handful of hardy space workers waiting for robots to replace them. For better or worse, Earth is the only place humanity will ever inhabit. We can also forget about encountering Earth-like organisms in our own or other planetary systems. Barrow and Tipler place the odds at less than 10-10. Belief to the contrary, they posit, comes from the “expectation that we are going to be saved from ourselves by some miraculous interstellar intervention.”10 In other words, Earth contains all the life humanity will ever know.

The question then arises: what kind of home must we have to survive as a species? In 1969, coinciding with Neil Armstrong’s “Giant Leap for Mankind,” Ian McHarg offered an answer. He was aware of the stakes. In Design with Nature, a view of Earth from Apollo 8 headlines the chapter entitled The Earth as a Capsule. In it, McHarg imagines a visiting astronaut studying ecology to cope with the planet’s biota. “We can use the astronaut as our instructor: he too is pursuing the same quest. His aspiration is survival—but then so is ours,” he wrote.11 The McHarg Center at the University of Pennsylvania sustains the clarion by promoting research on the future of all life on Earth. And yet, wild flora and fauna continue to be ravaged. It is not a winning formula. As Richard Weller asserted in The Landscape Project, “we are clinging by our fingernails.”12 To keep us from falling into the abyss, a massive reaffirmation of biodiversity as condition for our survival must take place. The United Nations Sustainability Goal 15 (Biodiversity and Ecosystems) firmly states the intrinsic value of biodiversity, recognizing the “negative impact that [its degradation] has on food security, nutrition, access to water, health of the rural poor and people worldwide.”13 COP 15, held in Montreal in 2022, advanced this goal by calling for the conservation of 30 percent of the planet’s land, water, and seas. The target is an improvement over the currently achieved 17 percent but well short of E.O. Wilson’s more compelling “Half Earth” target.

But wildlife conservation is not enough. From a survival standpoint, suffusing cities with nature is critical. And yet, the UN’s same sustainability goal fails to advance access to nature or nature-based design as objectives. The Sustainable Cities and Communities Indicators for Resilient Cities report (International Standards Organization 37123) commendably addresses ways to standardize ecological restoration and service, applied to the scale of forests, mangroves, and floodplains. The Global Program on Nature-Based Solutions, funded by the World Bank, is similarly focused on the larger domain of ecosystem services. But they equally fail to address the restorative and biophilic benefits of urban flora. There is ample research backing such health benefits: just ask Eugena South, a teaching doctor at Penn Medicine and Faculty Director of Philadelphia’s Urban Health Lab. Dr. South and her colleagues have documented how urban vegetation reduces stress and anxiety, gun violence, chronic ailments such as diabetes, and helps deliver healthier babies.14 With such evidence on hand:11

- Why is it so difficult to recognize and act upon the essentiality of nature in cities as an antidote against human illness or demise?

- Why can’t cities be designed with the same fail-safe rigor as we do space stations—as if life depended on it?

- Why, if plants and gardens are deemed essential for space habitats, can’t we use the same logic for urban habitats?

Yes, retrofitting and maintaining cities loaded with vegetation would be expensive. But what is the price of survival?

From Apollo 8, Jim Lovell observed: “The Earth from here is a grand oasis in the vastness of space.” He could not have predicted that fifty-seven years later the “oasis” would have to be 1.8 times larger to sustain humanity, and not simply from a resource standpoint. 16 Lovell’s words are biophilic in meaning: they echo Humboldt’s love-filled reflections about nature’s beauty. When we lose direct access to nature, we lose ourselves. When we degrade the planet, we fray the tie to the womb that birthed us. Severance will kill us.

Weller lamented the rare involvement of landscape architects in global conservation efforts. His concerns were not anecdotal. At a recent international conference held in Panama on Latin American voluntary conservation, ecologists, biologists, educators, activists, non-profit administrators and landowners outnumbered the few landscape architects in attendance, me included.

Ignacio F. Bunster-Ossa (FASLA, LEED AP) is the Vice President for Landscape Urbanism and Resilience at The Collaborative. He is an internationally recognized landscape architect with long- standing experience in the design of sustainable urban places. A recipient of numerous awards, Ignacio’s work is noted for the design integration of green infrastructure, community engagement and public art. His work includes the Master Plan for the Parklands of Floyd’s Fork, in Louisville, KY; the Georgetown Waterfront Park in Washington, D.C.; the SteelStacks Arts and Cultural Campus and Hoover-Mason Trestle in Bethlehem, PA; and Trinity River Corridor and Ron Kirk Pedestrian Bridge in Dallas, TX. Internationally, Ignacio led the master plan for Serena del Mar, a ten-thousand people new community in Cartagena, Colombia; and the Open Space Plan for the Isthmus of Panama, as part of an Interamerican Development Bank funded effort to comprehensively plan the metro areas of Panamá City and Colón. Ignacio is a Fellow of the American Society of Landscape Architects and past member of its Climate Change Committee. He is an Advisory Board Member of the McHarg Center for Urbanism and Ecology at the University of Pennsylvania, and member emeritus of the Landscape Architecture Foundation. He also periodically lectures and teaches, most recently at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design. Ignacio holds a Bachelor of Architecture from the University of Miami (FL), a Master of Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning from the University of Pennsylvania, and a Loeb Fellowship in Environmental Studies from Harvard University. He is co-author of Green Infrastructure: a Landscape Approach (an APA Planning Advisory Report), author of Reconsidering Ian McHarg: the Future of Urban Ecology (Planners Press), author of Limbs, Leaves, and Hope: A Portrait of Philadelphia’s Urban Forest in Times of a Pandemic (ORO Editions), and ALFIE: Earth’s Last Hope, an eco-science fiction novel (Inspiration Pointe Press). He is currently co-editor with Fritz Steiner of Penn’s Sylvania: Campus as Landscape, to be published by the University of Pennsylvania Press in 2026.

Works Cited

- Asimov, Isaac. "Runaround." In I, Robot, 33–55. Doubleday, 1950.

- Barrow, John D., and Frank J. Tipler. The Anthropic Cosmological Principle. Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Botting, Douglas. Humbolt and the Cosmos. Sphere Books, 1973.

- Kurzweil, Ray. The Singularity Is Nearer: When We Merge with AI. Viking, 2024.

- McHarg, Ian L. Design with Nature. Published for the American Museum of Natural History by the Natural History Press, 1969.

- Weller, Richard. "Introduction." In The Landscape Project. Applied Research and Design Publishing, 2022.

- Wilson, Edward O. Half Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life. W.W. Norton Company, Inc., 2016.

This article is part of a series of essays exploring topics inspired by “Landscape First” hosted at The University of Texas at Austin in the spring of 2025 with the generous support of the Still Water Foundation. All opinions, views, and provocations expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the official positions, policies, or perspectives of the School of Architecture.

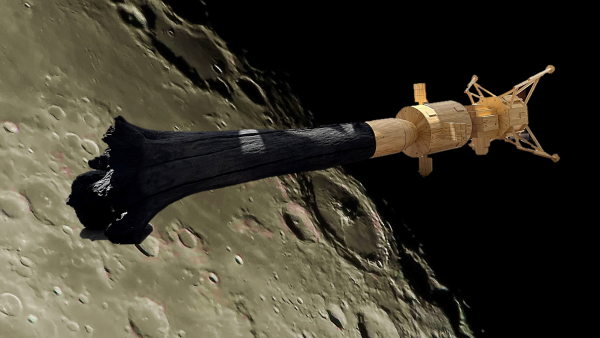

Figure 1. Composite artwork by the author featuring a wood sculpture by artist Cristián Salineros. The 28-foot piece was exhibited in 2022 at the School of Art of the Catholic University in Santiago, Chile. The artist wrote: “The piece has to do with the colonizing utopias beyond our planet, where action is valued over reflection, immediate return over long-term projection.”

READ THE ENTIRE LANDSCAPE FIRST ESSAY SERIES HERE →