Meet Visiting Faculty Karel Klein

Karel Klein is an architect and educator who has been working with various artificial intelligence technologies since 2016. Her ongoing project is an investigation into crossbred image-objects produced using atypically trained GANs and their capacity for contemporary mythmaking in architecture. With these tools, Karel is interested in the re-enchantment of the architectural body—one that both foments and succumbs to sensual perceptions and one that discovers new and unexpected relations to the world beyond the realm of the rational.

Her work in this domain has been exhibited at the Venice Biennale, 2021, the FRAC Institute, Orleans, France, Des Lee Gallery, St. Louis, and SCI-Arch Gallery, Los Angeles. A recent lecture, “Sing, Goddess,” was given at UT Austin in May 2023. Karel currently teaches at SCI-Arc, Washington University, and University of Pennsylvania.

We recently caught up with Karel to learn more about her and her work.

You teach at SCI-Arc, Washington University, and University of Pennsylvania. Can you tell us more about what appealed to you about joining the University of Texas at Austin as a visiting faculty member this fall and what you have found so far to be unique about UTSOA and its students?

My introduction to UTSOA came through a lecture I gave in spring 2023, which focused on my work with StyleGAN training and essays on aesthetic theory, memory, and metaphor. The thoughtful discussions that followed were the start of a deeper connection with the school community.

What drew me to join UTSOA as a visiting faculty member this fall was the opportunity to build on that initial interaction. I've found that UTSOA fosters an environment where students are both well-grounded in architectural fundamentals and eager to explore innovative approaches. This balance mirrors my own desires to stitch together core aspects of the architectural discipline with theoretical concepts with experimental techniques and technologies.

The school has been incredibly supportive in allowing me to develop a technically advanced studio that incorporates developing AI workflows. This studio builds on my previous research but takes it in new directions, exploring how AI can inform and transform architectural thinking. The students' talent and motivation have made this an especially rewarding experience.

I'm excited about the potential to push boundaries and explore new territories in architectural education here at UTSOA.

Could you tell us more about the studio you’re teaching this semester, “The Atomic Uncanny: Estranging the Case Study Houses”?

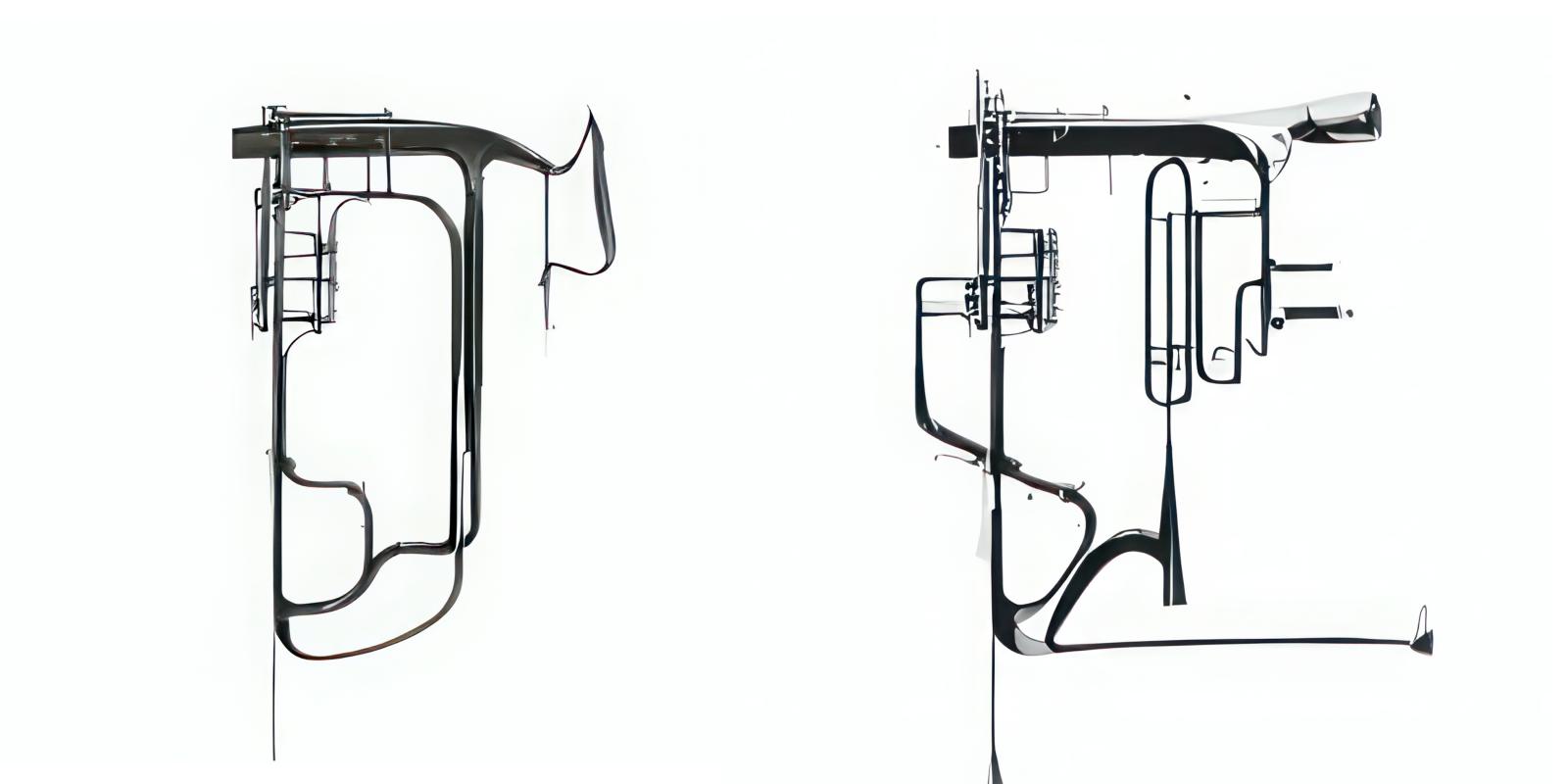

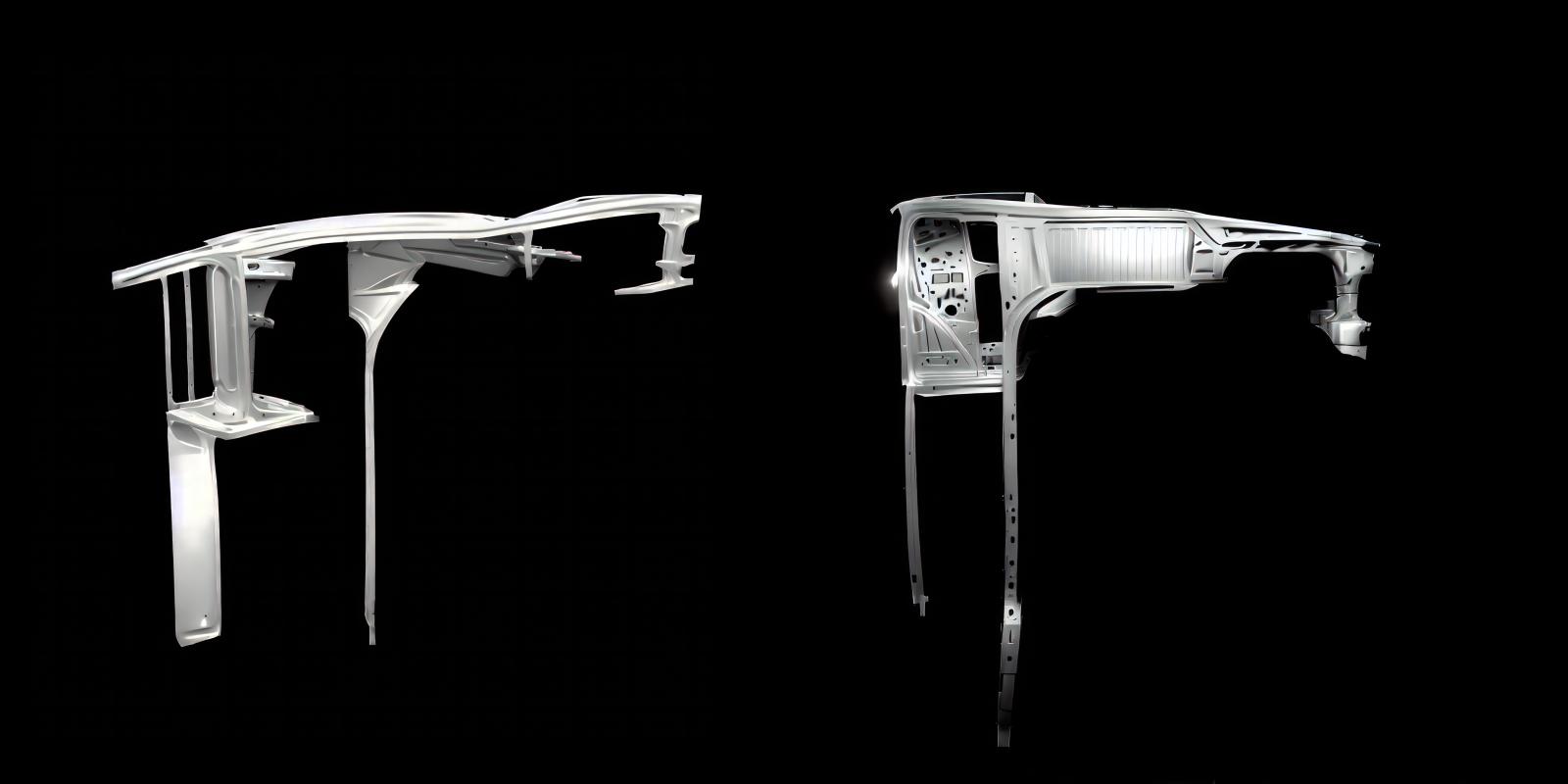

The "Atomic Uncanny: Estranging the Case Study Houses" studio explores the AI-driven transformation of mid-century modern architecture. We begin with the Case Study Houses program — a series of experimental, modernist residences built primarily in Los Angeles between 1945 and 1966. Each student selects and accurately 3D models one of these iconic houses.

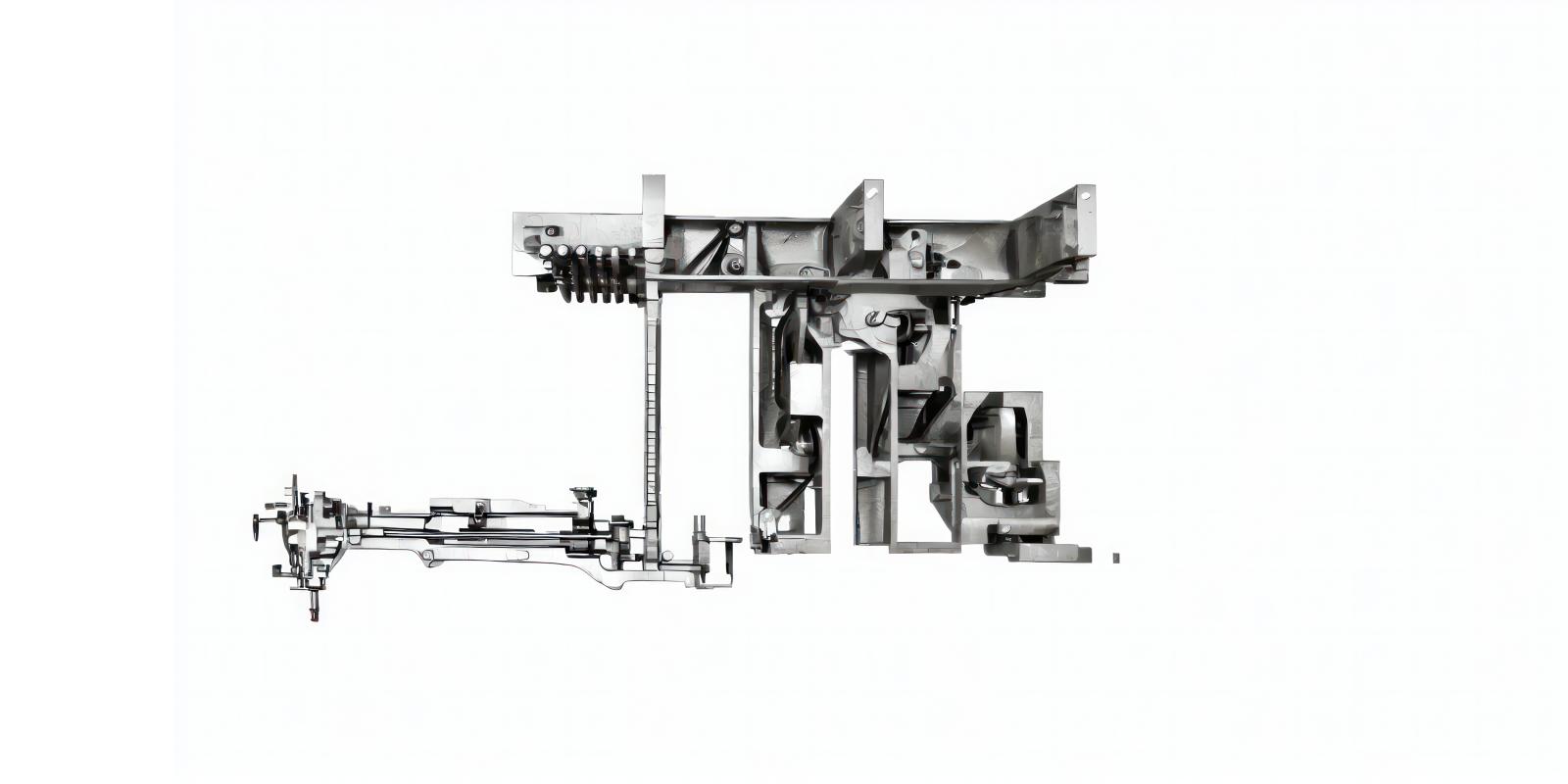

Our process then involves breaking down these models into components, encouraging a critical re-examination of architectural composition. We start by "chunking" the house, an initial step that reveals new compositional relationships, afterward identifying smaller "parts" within these chunks for further manipulation.

This studio uniquely focuses on AI transformation at the tectonic level, using fully 3D models as both input and output. Unlike typical generative AI in architecture that often deals with style or 2D imagery, we maintain overall form while introducing changes at the detail level. This approach allows for a more precise and architecturally relevant form of estrangement.

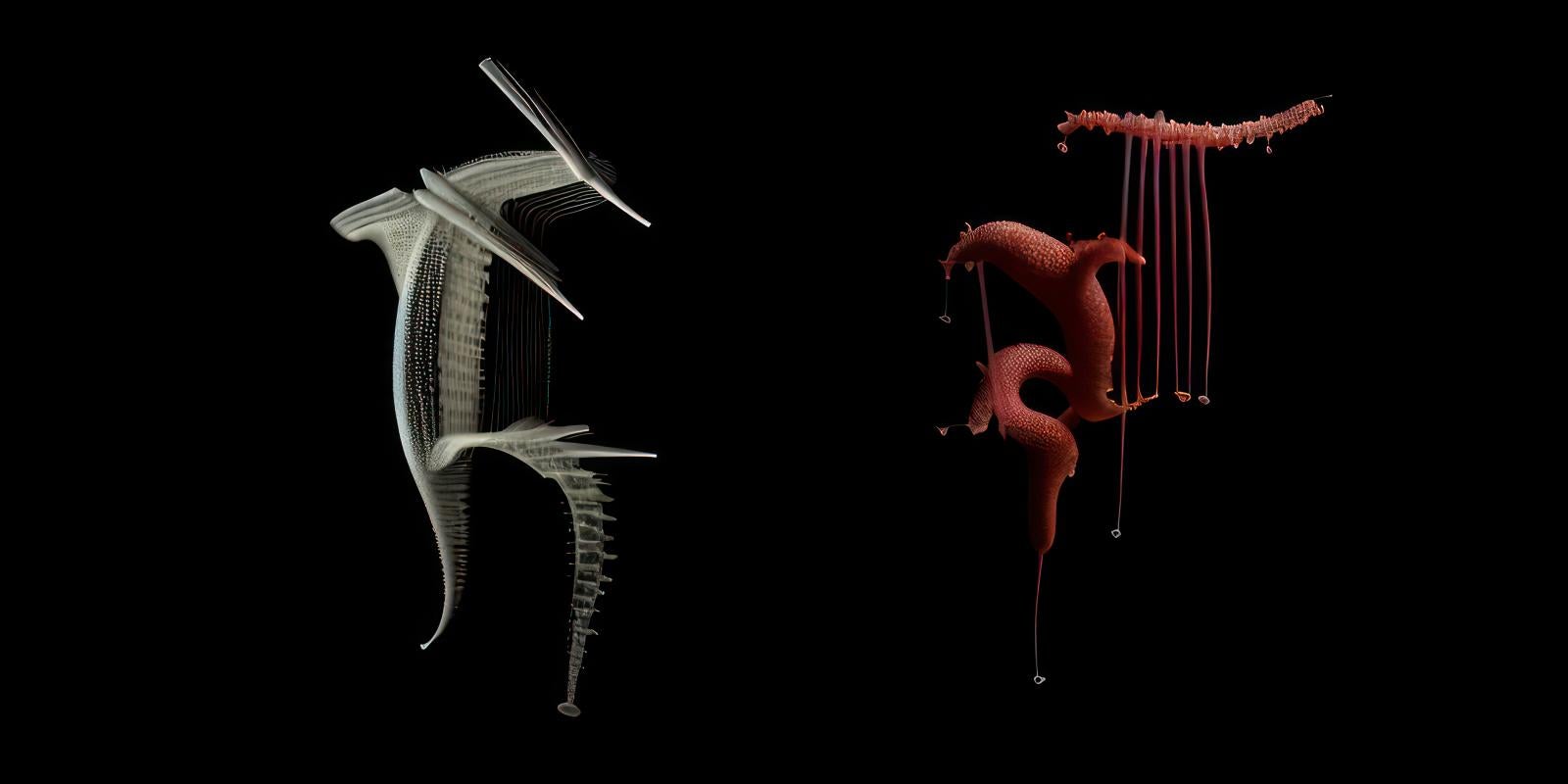

Students train custom AI models on diverse object categories to alter the geometry, materials, and features of the architectural elements. The resulting "uncanny" parts, still in 3D form, suggest possibilities for the re-assembly of the houses in novel ways. This method of applying AI at the component level allows for a different level of control, or agency in architectural design.

Finally, we ground this work in theory, studying Anthony Vidler's "The Architectural Uncanny" and examining Freud's concepts of "heimlich" and "unheimlich" in relation to domestic architecture. This framework contextualizes the AI-generated mutations within broader cultural and psychological discussions.

By combining historical analysis, advanced 3D AI techniques, and architectural theory, the studio pushes the boundaries of architectural form and manipulation, focusing on precision within estrangement.

Your research and work investigate how artificial intelligence can expand and inspire creativity and the “re-enchantment of the architectural body,” Could you give us some examples of how you’ve put this exploration into practice, either through your work with Ruy Klein or your teaching (or both)?

My exploration of AI's potential to expand creativity and re-enchant the architectural body is best reflected in both my written work and in my teaching.

For instance, in one essay called "To Think a New Thing: AI, Metaphor and the Fantasies of Knowing," I write about what is shared between linguistic metaphors and AI-generated images, particularly those created by mistrained StyleGAN models. This essay explores how both metaphors and AI-generated images create new "objects" that transcend their constituent parts, embodying a form of knowledge that is felt rather than articulated. These new entities occupy what Ortega y Gasset calls the "(a)esthetic realm," where beauty begins and where the familiar becomes unfamiliar, leading to new perceptions and understandings.

The studio I’m currently teaching at UTSOA works on a practical application of these ideas. Here, students use AI to transform the Case Study houses at a tectonic level. By breaking down these familiar architectural forms and reconstructing them using AI-transformed components, we're literally re-enchanting these well-known architectural bodies.

In the newly re-figured, re-featured, and re-assembled houses, re-enchantment is palpably evident. These AI-assisted designs challenge our perceptions of domestic space, materiality, and form, asking us to reconsider our relationships with the built environment. They embody the concept of re-enchantment by infusing familiar architectural forms with unexpected qualities, creating a sense of the uncanny — familiar yet unusually and unexpectedly unfamiliar.

Working with various artificial intelligence technologies for nearly the last decade, how do you see design education further exploring and integrating these technologies over the next decade?

While I can't predict the broad trajectory of design education, I am personally interested in advancing pedagogy and practice by means of re-imagining the design process itself. In my current studio at UTSOA, the integration of AI technologies allows us to reconsider fundamental aspects of architectural conception and production. This approach not only enhances technical proficiency but also expands the boundaries of what we consider possible in architectural design.

What is something that students and colleagues should know about you? Besides your work, what is something you are passionate about, or what do you do for fun?

Beyond my professional work, I find great joy in spending time with my children. However, my passion for language and literature significantly influences my approach to architecture. I'm particularly drawn to writers like William H. Gass and Donald Barthelme. Gass, a master of metaphor and an aesthetician of language, crafts sentences of extraordinary beauty. Barthelme, on the other hand, is a designer of form through language. Both create entirely new entities with their words.

Reading these authors, I'm inspired to seek similar innovation in architecture. Their work resonates with my interest in memory (à la Proust) and metaphor and informs my exploration of AI in design. My intuition is that AI can teach me, perhaps, how to do to, or with, architecture what these writers do with language — creating new realities that challenge our perceptions and expand our understanding of what's possible.