Q&A with Assistant Professor Martin Hättasch

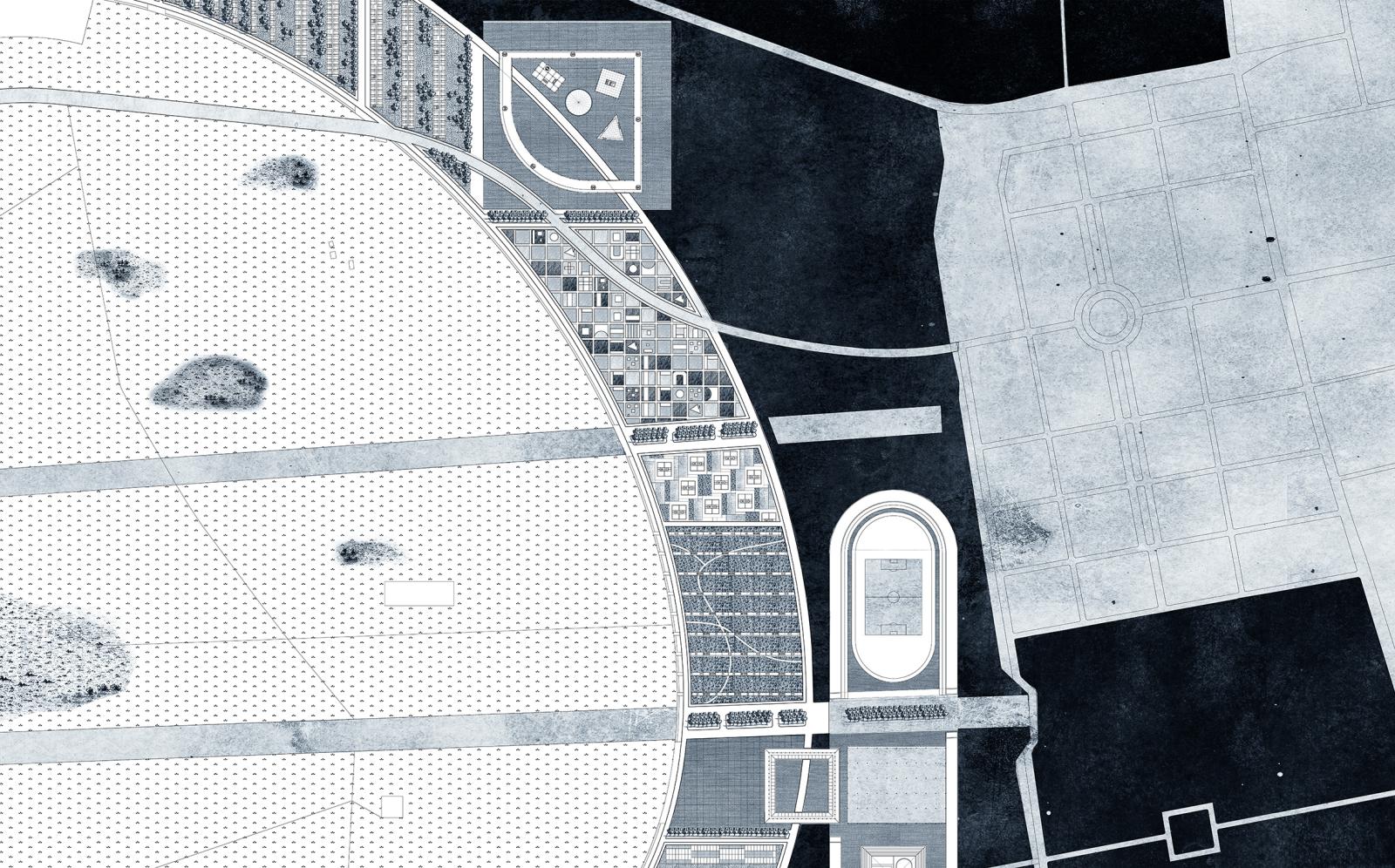

Martin Hättasch is a German architect whose design and research focus on the intersection of architecture and urbanism, housing, monumentality, and their numerous overlaps. A registered architect in the Netherlands, his work explores relationships between finite form and open-ended use across scales and includes the design of several exhibitions, as well as a master plan for the former airport Berlin Tempelhof.

Hättasch’s studio, “A Home is Not a House,” focusing on the question of medium-density housing, was awarded the 2018 Architect Magazine Studio Prize, and he is the recipient of the 2022 ACSA/AIA Housing Design Education Award. On Friday, November 10, Hättasch is hosting a symposium organized by the Center for American Architecture and Design exploring the potential of medium-density housing and the “middle grounds” between established disciplines, practices, or processes as we seek new housing solutions.

As part of our new faculty profile series, we caught up with Martin to learn more about his research, interests, and upcoming symposium.

You’ve been a part of the School of Architecture as an adjunct lecturer for some time now. What are some things that have changed at the school over the course of your time here? How will your transition to an Assistant Professor impact and shape your research, work, and teaching?

The first part of the question is surprisingly hard to answer, as a significant amount of my time at the school has coincided with the COVID pandemic; so, I feel any changes I observe could either be substantial changes in one direction or temporarily caused by the pandemic, or even both. Just as we all are, I am still trying to come to terms with what certain changes in the last three or so years actually mean. For my part, I have become much more flexible in the way I teach, incorporating synchronous and asynchronous methods in effective ways beyond what I ever thought was possible in a design studio. From what I see, students have become more open to new ideas and are interested in a wider variety of input than maybe a few years ago – more “cosmopolitan” if you will. At the same time, I hear a lot of concerns about careers and finding a stable position in practice after graduation. Maybe both are the results of the uncertain times that COVID made everyone feel we live in.

As for my research, I am very much looking forward to the new opportunities a tenure-track job provides to advance my design and research efforts. Interestingly, my new status here at UTSOA coincides with the new deanship, and I think this has contributed to a sense of a new beginning for me.

Housing is obviously one of the major challenges we’re facing here in Austin and around the country. Your work and teaching at the School of Architecture have focused heavily on “medium-density” housing – You even won an Architect Magazine Studio Prize for studios you developed around the topic. Could you talk a bit about housing, in general, and how solutions like medium-density housing might make a difference?

Housing is probably among the major challenges we are facing today as a society (along with AI and climate change…). In my view, it’s imperative that we find responses to these challenges, maybe partial and imperfect ones at first, but we must engage with these questions as a practice and discipline, as they relate to our field.

While housing involves many disciplines, there is undeniably a strong design component involved – the way we conceive of the smallest spatial living unit has tremendous implications for what our cities look like, for better and for worse. Much of my studio teaching on the topic is also an attempt to foster a design-based discourse on housing – which was practically non-existent when I was a student. I hope to make architecture students aware of these challenges and issues and prompt them to use their skills to tackle the housing question – in school and beyond.

When I first started to teach a design studio around the question of medium-density housing, it was almost an accident. I had just moved to Austin and was looking for a more permanent place to live. There were really only two choices: single-family houses that were either out of my price range or incredibly far outside the city center or small apartments with bad natural light and no outside space to speak of. So, my first housing studio was somewhat of an attempt to define what a desirable living situation would have looked like for me. Of course, as I have learned since, these issues are systemic, and, over the last decade, there has been a growing discrepancy between large-scale apartment blocks with ever smaller apartments and the economically and ecologically unsustainable free-standing single-family house.

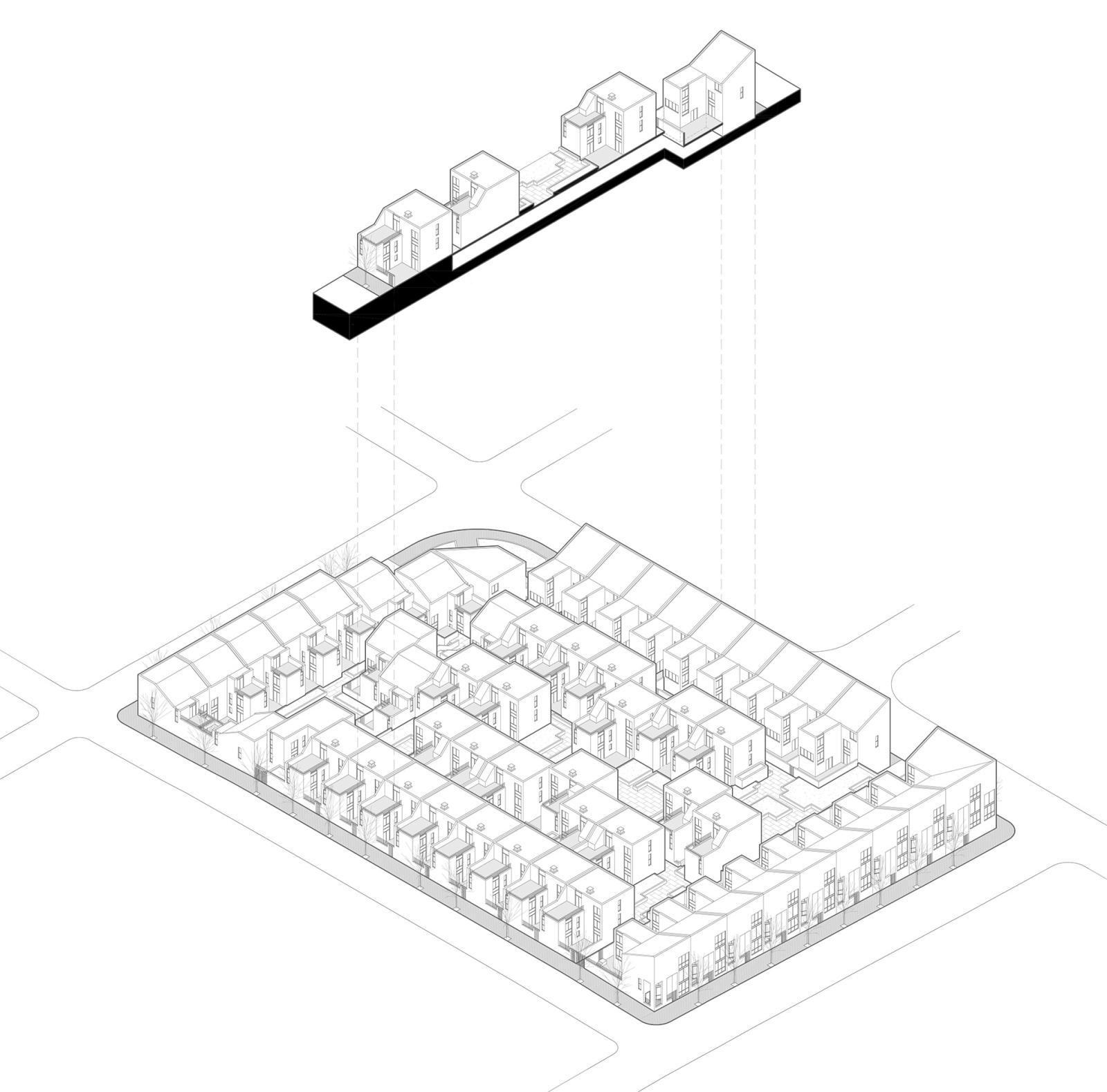

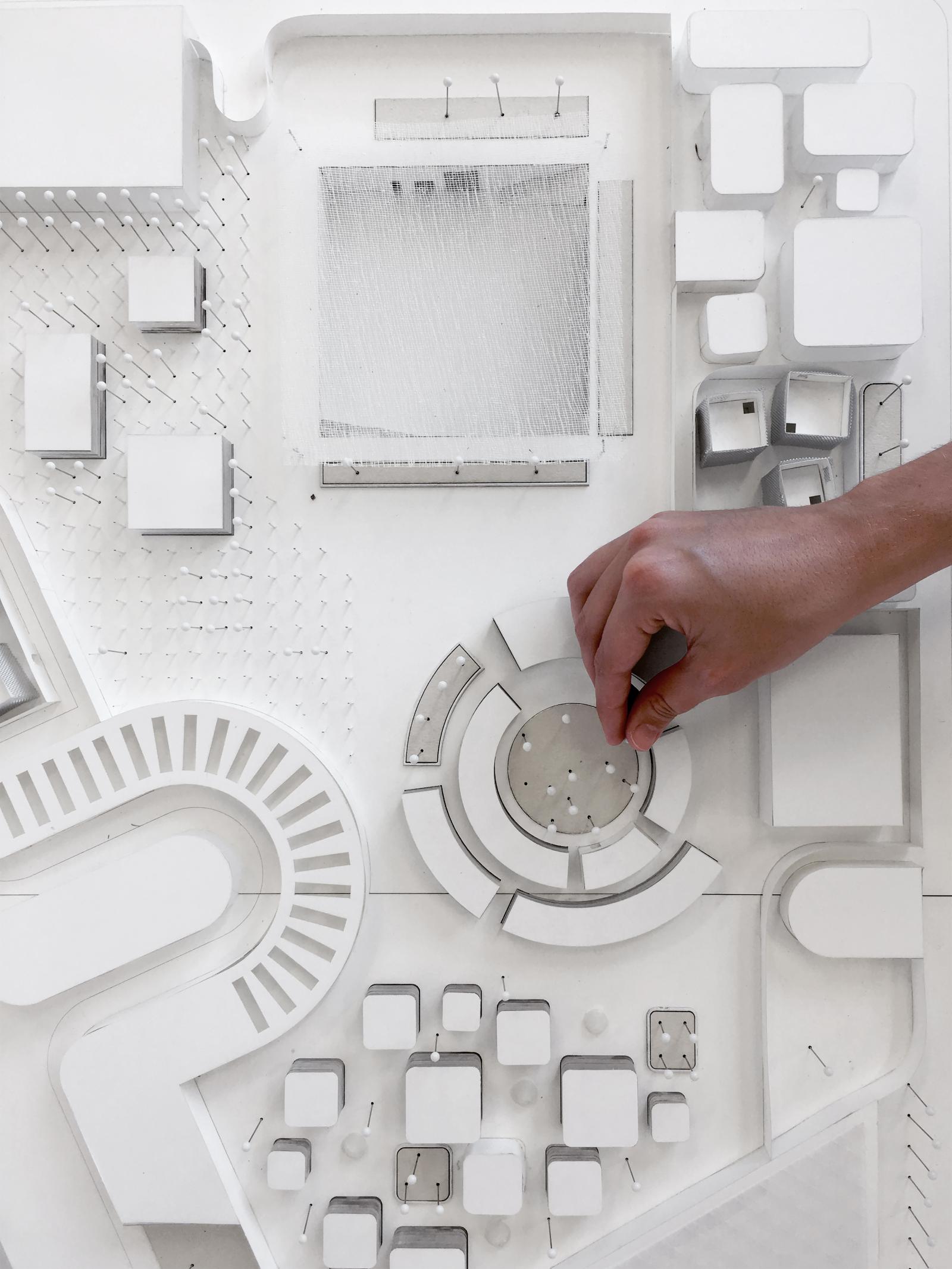

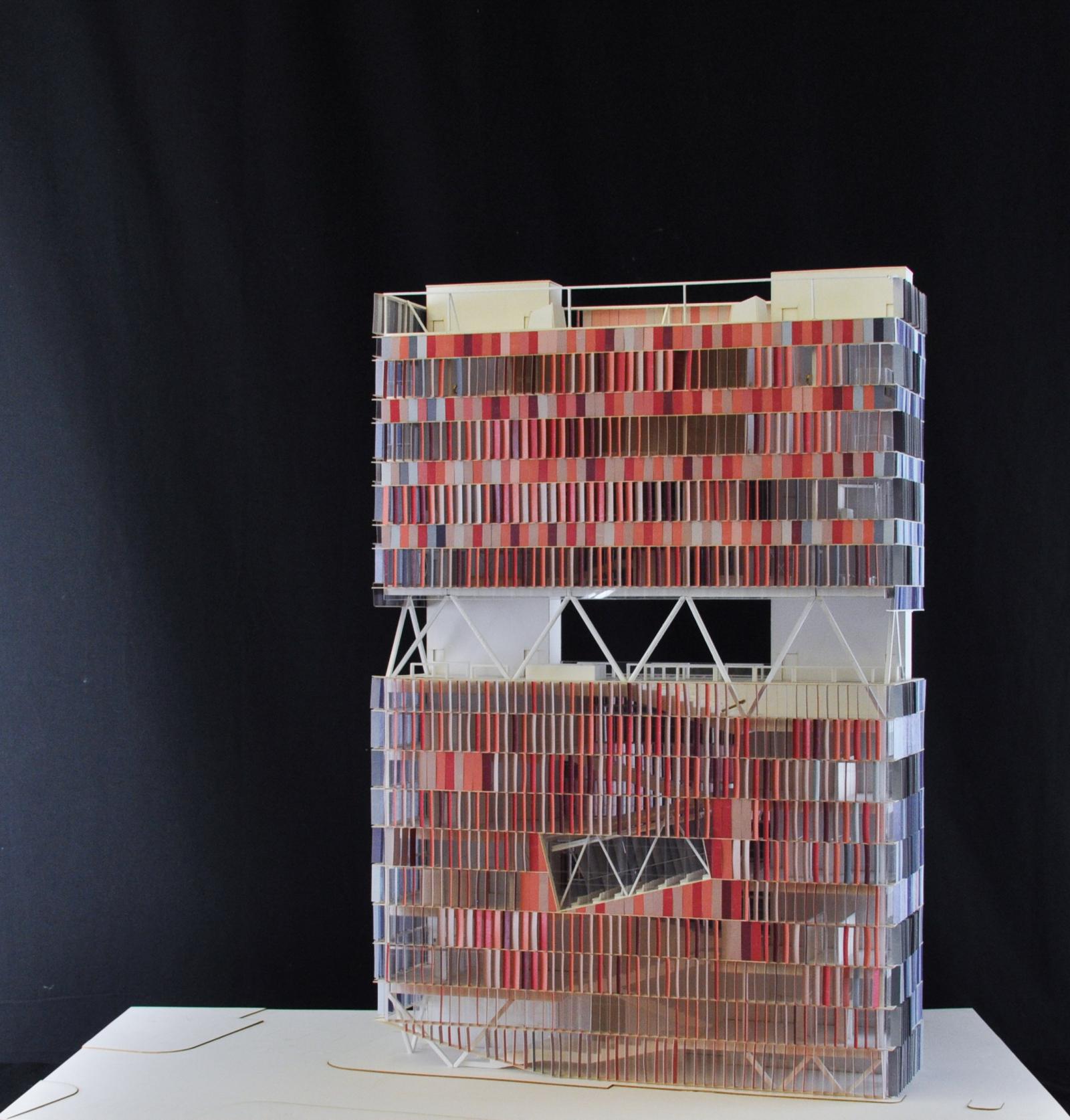

The medium-density range, sometimes called the “missing middle,” is a range that can potentially fill this gap. To me, this range is also interesting from a design point of view because it is incredibly spatially malleable. There is a lot of space for architectural speculation on how units respond to new models of cohabitation, how they form collective spaces, or how they come together materially and constructively. At higher densities, you lose some of this freedom because types and construction are often predetermined within very tight limits, and the single-family scale excludes many of these collective ambitions by default.

You’ve lived and worked all over the world. What are some lessons or ideas you’ve taken away from other places that could be implemented here?

If anything, one of the lessons for me has been that different things work in different places and that there will never be wholesale solutions that can be transferred from one place to another; that goes for my own design, my teaching, and, in a larger sense, for practices of housing in general. That said, I would say that my experiences in these different contexts have clearly given me certain biases and ways of looking at things, but also an awareness of everything out there for us to look at and learn from. I try to bring these biases into my design studio without insisting on particular solutions. Mostly, I ask students to suspend their disbelief and follow me down rabbit holes that may be new to them and present opportunities to look at known problems through new lenses.

A topic like housing is complicated, with many layers and dynamics beyond the architecture and design. Why is it important for architects to engage with others in allied disciplines on these types of challenges? Could you talk about some of the interdisciplinary research projects you’ve been a part of through the Center for Sustainable Development?

Housing is – as you say – an incredibly complex enterprise that involves many sets of expertise, disciplines, and dynamics. But, as much as we like to – somewhat self-critically – remind ourselves that architects can’t solve all housing problems by themselves, it is also important to remember that other disciplines can’t either. Architecture and architects have much to offer to this debate, and the current housing crisis makes it more than apparent that customary ways of producing housing have reached an impasse. Any new approach will have to involve a certain kind of out-of-the-box thinking, possibly new forms of out-of-the-box interdisciplinary collaboration, and I see an opening here to (re-)insert questions of design into the housing debate.

As many cities (including Austin) are struggling to reform zoning and to consider better ways to not only make housing but also to make a better city, I witness a renewed interest in questions of design from outside our field. As we enter unknown territory, people want to know: “What could it look like?” – a question that architects are traditionally very good at answering. One of the challenges is creating mechanisms and forums where these collaborations can happen outside the customary practices and procedures.

The Center for Sustainable Development is a great asset for this type of research here at UT. With the CSD I was involved in developing scenarios for a 19-acre site of a former big box store in Austin’s St. John neighborhood, a project that involved collaborations with city departments and a process of community input and outreach in a historically disadvantaged neighborhood. It was an amazing learning curve for me to understand the different motivations and priorities of the constituents involved in the process. I came away with a much more nuanced understanding of what it takes to bring (affordable) housing into existence.

Tell us about your upcoming symposium and exhibition. What can people expect from the conversation on November 10 and the accompanying exhibition?

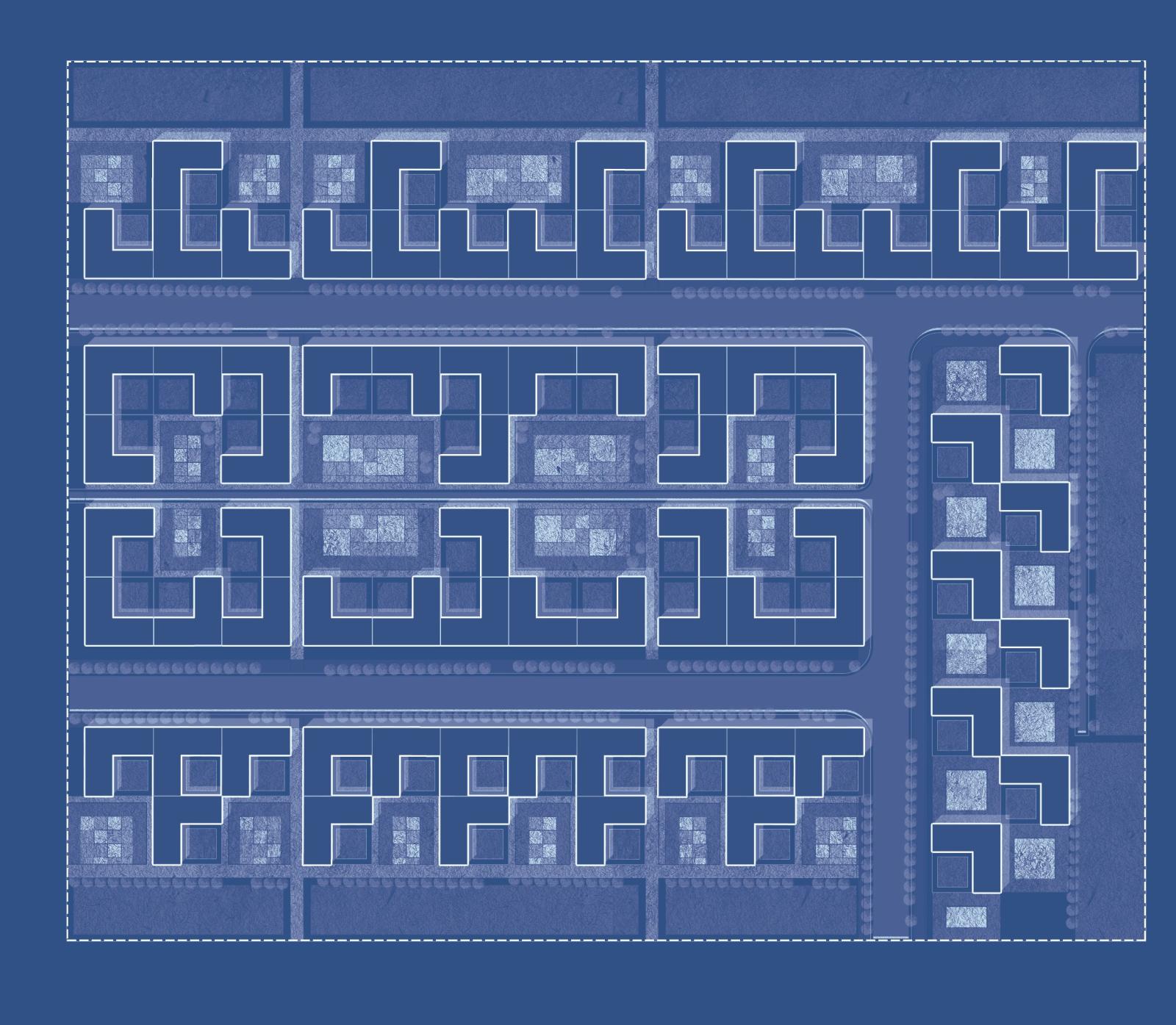

The symposium is titled “Radical Middle Grounds – New Agendas for Medium-Density Housing.” It will bring together architects, historians, urban designers, and economists whose practice and research on housing is defined by the “out-of-the-box thinking” I mentioned above. The middle ground has a dual meaning here. On the one hand, it describes a medium-density range of housing beyond the established extremes of (suburban) houses and (urban) apartments (often described as “missing middle” housing), characterized by an incredible spatial malleability. On the other hand, it hints at how participants mine grey zones between established disciplines, practices, or processes in search of new housing solutions.

Participants will present work in three sessions – or “middle grounds” – addressing housing as a question of Urbanism (“Between Unit and City”), Process (“Between Politics and Form”), and Design (“Between Typology and Invention”). I am incredibly thrilled that we will have a fantastic cast of speakers, including Brian Phillips, principal of Interface Studio Architects (ISA), one of the most progressive architectural practices working on housing design in the U.S. today, Marc Norman, Larry & Klara Silverstein Chair in Real Estate Development & Investment, and associate dean of the Schack Institute of Real Estate at NYU, and Neeraj Bhatia, founder of The Open Workshop, Associate Professor at the California College of the Arts and director of the urbanism research lab Urban Works Agency.

A small exhibition will accompany the symposium that showcases the forthcoming volume of Center, published by the Center for American Architecture and Design, titled Center 25: Radical Middle Grounds, featuring essays and projects that redefine what it could mean to operate on the middle ground.