Q&A with Associate Professor Aleksandra Jaeschke

Aleksandra Jaeschke is an architect and an Associate Professor of Architecture and Sustainable Design. Born and raised in Poland, she holds a Doctor of Design degree from the Harvard Graduate School of Design, and an AA Diploma from the Architectural Association in London. Prior to joining the faculty at the UT School of Architecture, she taught at the Woodbury School of Architecture in Los Angeles. During her time at the UT School of Architecture, Aleksandra published her first book and contributed to a number of publications and public events.

Aleksandra’s recent scholarship has explored and questioned the validity of the frameworks used in architecture, emphasizing the importance of integrating knowledge from other domains, expanding system boundaries, and embracing non-Western perspectives. Her current research investigates the ecological consequences and design opportunities arising from material choices, advocating for a more culturally diverse and ecologically attuned relationship between architecture, agriculture, and natural preservation.

To celebrate Aleksandra’s recent promotion and tenure, we caught up with her to learn more about her research, and her efforts to move towards a more holistic understanding of the built environment.

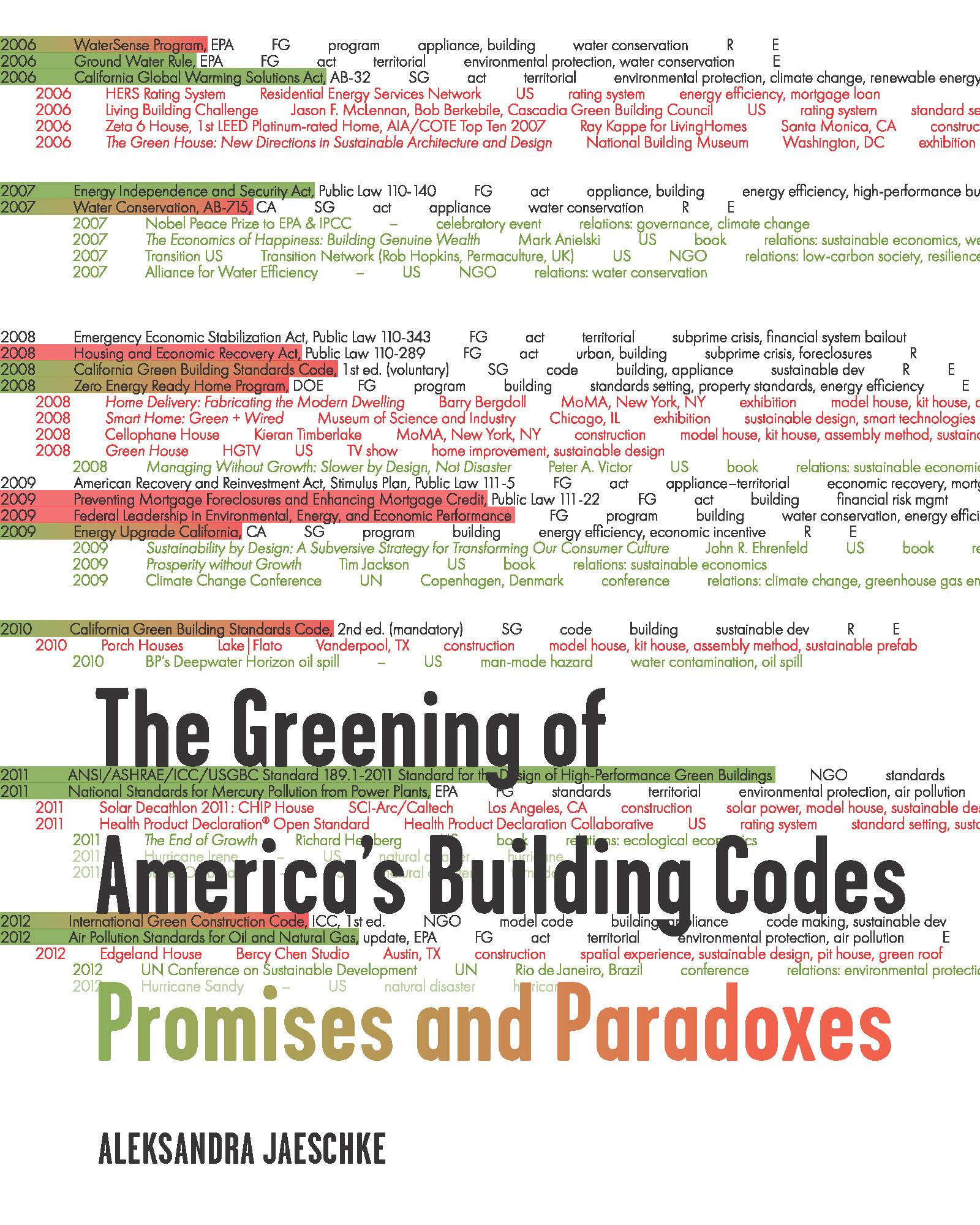

You recently published a book, The Greening of America’s Building Codes: Promises and Paradoxes, based on your doctoral dissertation at the Harvard GSD. Could you give us an overview of the book and some of your insights and takeaways?

In the book, I explore the interplay between environmental goals and the regulatory frameworks that have shaped America’s construction industry. As part of my doctoral research, I surveyed the historical interactions between the ecological movement, technoscientific advances, socioeconomic agendas, regulatory programs, and architectural discourse to critically assess how building regulations and “green building” incentives shape what architects consider safe, healthy, and sustainable. The research revealed that the cultural, socioeconomic, and political forces and agendas that influenced the development of early building codes and financial instruments continue to define the character of current building regulations and incentives. These forces, in turn, determine how we build, regulate environmental impact, and define sustainability today.

I also examine the promises and contradictions of integrating sustainable goals into existing building codes. One of the central themes of the book is the tension between incremental progress and the need for transformative action. Codes inherently represent the status quo; they are written to codify long-established best practices rather than push boundaries. Moreover, while the green building standards recently incorporated into existing regulations aim to address pressing environmental challenges—such as reducing carbon emissions and promoting resource efficiency—they often prioritize technological solutions and technical compliance over natural alternatives and systemic change. As a result, these standards tend to focus on measurable, quantifiable aspects of sustainability while neglecting qualitative dimensions and the broader ecological context of the built environment.

The book also raises questions about who writes these codes and whose voices are included—or excluded—in the process. It challenges architects to go beyond mere compliance and engage with the deeper implications of their work, such as how materials are sourced, what social and ecological systems are affected, and what values are embedded in our definitions of sustainability. One of the key points I raise is that architects must act not only as designers but also as advocates, pushing for a broader, more integrative approach that addresses the root causes of environmental degradation.

And so, in addition to examining the origins of these narrowly defined frameworks and mindsets—sustainability and green building standards in this case—the book also offers a reflection on how we might expand the boundaries of our practice to trigger meaningful change. It highlights a range of successful “predesign” efforts, such as the development of new model codes and standards, technologies and products, computer programs, and financing mechanisms, to show how architects and allied professionals can lead the way toward a more sustainable future.

In lectures and conversations about your research and work, you’ve advocated for a more holistic understanding of the built environment—one that looks beyond the boundaries of our disciplines and incorporates voices from the outside world. In your opinion, what other disciplines or areas of expertise would have the most impact on architectural practice and discourse, and, more specifically, your area of expertise?

Architecture has historically been viewed as a discipline with distinct boundaries, focused on the design of buildings and spaces. However, the complexities of today’s ecological and social challenges demand that we move beyond these boundaries. A holistic understanding of the built environment requires input from diverse fields, particularly those that address the interconnections between people, ecosystems, and the material and energetic resources we use.

Recently, I have been exploring the field of agroecology, which offers insights into how we might lower the impact of food production on soil health, biodiversity, and water resources. All of which are crucial considerations when working with biogenic materials, since these include materials intentionally grown as crops, such as hemp, or agricultural byproducts like straw.

More broadly, environmental science provides frameworks and critical data for understanding the impact of our actions on the planet. I find the framework proposed by the Stockholm Resilience Centre especially useful. It helps us to think about everything we do in terms of its effects on the nine planetary boundaries. Some of these boundaries, such as climate change, are common topics in architectural conversations. However, most are not, even though they are fundamental to the planet’s health. The Centre monitors the following boundaries: (1) climate change; (2) change in biosphere integrity (biodiversity loss and species extinction); (3) stratospheric ozone depletion; (4) ocean acidification; (5) biogeochemical flows (phosphorus and nitrogen cycles); (6) land-system change (e.g., deforestation); (7) freshwater use; (8) atmospheric aerosol loading (microscopic particles in the atmosphere that affect climate and living organisms); and (9) introduction of novel entities (e.g., non-biodegradable plastics). The most recent update, from 2023, indicates that six of these nine boundaries have been transgressed, underscoring the urgency of rethinking our material choices and their broader implications.

Equally important are the humanities and social sciences. Anthropology, for instance, helps us understand the social and cultural underpinnings of architecture. It reveals that our cultural norms and behaviors are adaptive patterns, specific to their environmental contexts, rather than fixed entities. This perspective encourages questioning and altering those norms when they no longer serve us or the planet. Anthropology also highlights the culture-specific nature of knowledge production, reminding us that Western science is only one of many systems of knowledge.

Portuguese sociologist Boaventura de Sousa Santos critiques the Western "monoculture" that suppresses other systems of knowledge, impoverishing what he refers to as the "ecology of knowledges." On the positive side, there are signs of growing recognition of the value of Indigenous knowledge, which offers invaluable perspectives on living harmoniously with the land. These systems challenge Western epistemologies and propose alternative ways of thinking about resources, relationships, and resilience. Incorporating these voices not only enriches architectural discourse, but also equips architects to address the complex, interconnected challenges of our time. By collaborating across disciplines, we can move toward a more inclusive and ecologically attuned practice that acknowledges architecture’s role within a larger web of life.

Over the past several years, you’ve led various studios and initiatives around the idea of “Plant Potential.” Could you speak to your fascination with plants and their fundamental importance? Where did this interest in plants and our relationship with them begin?

The “Plant Potential” initiative emerged from a convergence of professional, academic, and personal interests. My fascination with plants began with a focus on materiality—specifically, the biomimetic insights we can gain by studying how plants are structured and how they function. This initial interest evolved into a broader exploration of the multifaceted roles plants play in ecosystems and in our lives: as living entities that shape landscapes, as essential ingredients in our diets, as a multi-sensory aesthetic experience, and as raw materials for construction.

Take straw, for example—a byproduct of wheat cultivation that is often dismissed as waste. For architects, it holds remarkable potential as a renewable and non-toxic insulation material. However, removing straw from fields has detrimental ecological consequences, as it contributes to soil nutrient depletion. Beyond that, industrial monocrop farming—such as wheat production—has already pushed several planetary boundaries to critical levels. Understanding these interconnected dynamics requires a systems-based approach that embraces broad system boundaries rather than reducing complexity to easily manageable compartments.

While it should now be evident that architecture must engage with the full life cycle of its materials, working with plant-based resources brings a unique sense of immediacy. Unlike fossil-based materials, whose living origins are buried in a distant past, plant-based materials were alive just moments ago. This temporal proximity introduces an existential resonance—plant-derived materials remind us that we rely on other forms of life and are part of the same living systems. Moreover, unlike geological formations, which operate on vastly longer timescales, plants undergo perceptible cycles of growth, decay, and regeneration. These cycles occur within our lived time frame and serve as tangible spatiotemporal markers, reflecting the rhythms of the planet. By engaging with plant-based materials, we connect architecture to these cycles and to a broader ecological temporality that is both immediate and planetary.

At its core, “Plant Potential” reflects a desire to rethink our relationship with plants, moving beyond a purely utilitarian perspective.

When you received the Mark Cousins Theory Award in 2021, you spoke about pushing boundaries and thinking about theory as a form of map-making. Could you elaborate on this idea and put it in context to how you think about teaching and the work we do as architectural educators?

Maps, like theories, are tools for navigating complexity. They offer frameworks for understanding and interpreting the world. Without maps, we get lost in the vastness of the world; without theories, we get lost in infinite and insignificant detail.

Charles Darwin’s remark that “all observation must be for or against some view if it is to be of any service” resonates with me profoundly. For Darwin, theory was not an optional overlay but an essential guide for meaningful observation. His insight reminds us that theory and observation are inseparable. Theory gives direction to our observations and ensures that they contribute to a larger discourse. Whether in natural sciences or architecture, observation and practice should always be informed by larger conceptual frameworks. Just as Darwin used theory to guide his exploration of natural phenomena, architects require theory to interpret and respond to the complexities of the built environment.

In my Wheelwright Prize research, which included extensive fieldwork in Spain, Morocco, Mexico, and beyond, and focused on the spaces of protected agriculture, I explored the greenhouse—often celebrated as a solution to food production challenges. What began as unframed observation gradually assumed theoretical significance. The greenhouse, sometimes referred to as a “forcing frame,” eventually became a metaphor for the reductionist tendencies embedded in Western epistemological and axiological frameworks. It evolved into a model—a tool for thinking about broader issues beyond this specific typology.

Models, in many ways, are key to theory. They allow us to move beyond isolated observations and view things differently. For me, theory is about charting connections and opening new possibilities. This involves engaging with history, philosophy, and sciences in ways that are critical, reflective, and open-ended. In teaching, I strive to create an environment where students feel empowered to question norms and experiment with ideas. By framing theory as a dynamic, exploratory process, I aim to instill a sense of curiosity and a willingness to engage with the complexities of the built environment in all its dimensions. I also encourage my students to embrace uncertainty. After all, theories evolve, some end up being wrong, and one must be prepared to evolve with them!