Q&A with Elizabeth Mueller

Elizabeth J. Mueller’s work focuses on the ways that patterns of economic and racial segregation and inequality were established and continues to be produced in growing cities. She has examined how contemporary local planning initiatives aimed at increasing density and reducing driving affect patterns of racial and economic segregation and exposure to environmental hazards and poor housing conditions.

As a PI or Co-PI on several research projects, she is currently studying:

- The past and ongoing role of planning in shaping existing patterns of segregation/inequity in Austin;

- How non-institutional landlords make decisions regarding rental housing ownership and management; and

- The historical factors shaping how zoning protects or exposes particular groups and communities to environmental hazards and other threats to property values and living conditions.

Her work is currently funded by the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

She is co-editor of The Affordable Housing Reader (second edition, Routledge, June 2022) and co-author of Uprooted: Gentrification in Austin’s Residential Neighborhoods and What Can Be Done About It (2018), a report commissioned by the Austin City Council.

She has received awards for her teaching, research, and public service and has been a member of the Community and Regional Planning faculty at The University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture since 2006.

You literally wrote the book on affordable housing –The Affordable Housing Reader (both the first and second editions). How did you come to specialize in affordable housing within the larger field of planning?

It really was accidental. I came to UT while on leave from my position at the New School for Social Research in New York City. During that period, I was invited to co-teach a project course at the LBJ School focused on affordable housing. There were a few people at UT thinking about housing issues, but not many. And local advocacy around the issue was nowhere near what it is now. My work, up to that point, had been more focused on problems facing the working poor in cities and the marginalization of low-income communities. After that course, I worked on a report for the Austin Community Action Network (since renamed the Community Advancement Network) focused on the growing unaffordability of housing in Austin. The resulting report, Through the Roof, laid out many issues we continue to struggle with. In recent years, I’ve begun thinking a lot more about the role of rising economic inequality in deepening our housing challenges and ways to bring that back into my work.

In both your research and teaching, you work across disciplines. You’ve collaborated with partners in the School of Law, LBJ School of Public Affairs, and beyond, and you also have a faculty appointment in the School of Social Work. Could you talk a bit about the value of interdisciplinary collaboration, particularly when it comes to such complex issues as affordable housing?

Housing has been described as a gateway to other rights. Lack of access to stable, decent, and affordable housing makes it hard for children to do well in school, for adults and children to stay healthy, and for residents to advocate for themselves to local institutions and decision-makers. The quality of the environment and public services available where one lives also has a huge effect on residents. For me, housing is the lens through which I view issues of inequity in cities since it locates people in specific places that are linked to or excluded from various kinds of opportunities, or that provide them healthful homes and environments or expose them to various kinds of environmental harms. And planning has a strong role in that.

Hurricane Katrina happened not long after I became an Assistant Professor of planning and social work. I worked with colleagues in the School of Social Work on the struggles of Katrina evacuees coming to Austin. My role was to try to understand why recovery assistance was so hard for many low-income renters to obtain. I learned a lot about the intersection of housing with other kinds of assistance and the treatment of the poorest evacuees through that project. I always cross-list my housing class with Social Work, and those students add so much since they draw on their experience working directly with people struggling to find decent, affordable housing.

In recent years, I’ve become more interested in housing conditions and how poor conditions affect residents’ health. Last year I joined a team of air quality and asthma researchers at the Dell Medical School to propose a project to the National Institutes of Health. We got the grant, and I am now working on assessing the role of land use, planning, and other regulatory processes in creating inequitable patterns of exposure to types of air pollution that cause or exacerbate asthma. It’s been fascinating for me to learn about the ways that public health and air quality researchers frame and research these problems and for me to find ways to link what I do to their work. I hope, together, we can bring more attention to ways we can prevent or reduce the exposure of residents to health hazards. I think it will require some pretty profound changes in how we think about land use and zoning.

I also often collaborate with a colleague in the Law School on projects aimed at strengthening housing choices for low-income residents, especially renters, and through this work, I have learned a lot about the power of various stakeholder groups involved in housing issues, especially at the state legislature. I find that solutions often require bringing together people with a range of perspectives on housing problems, who understand both the big picture and conceptual issues that must be considered, and the pragmatic factors that will determine if a solution actually works. But most fundamentally, I have learned that it is critical that the voices of the people whose lives are most affected by the lack of decent, affordable housing need to be put front and center in these processes. Otherwise, programs often focus more on what works best for investors or developers even if the result does little for those who are the intended beneficiaries of policy. This means that I work not just with academics from different backgrounds but also with advocates and organizers who can bring residents into the conversation to speak for themselves. And I also serve on City Boards and Commissions to learn more about how policies work on the ground.

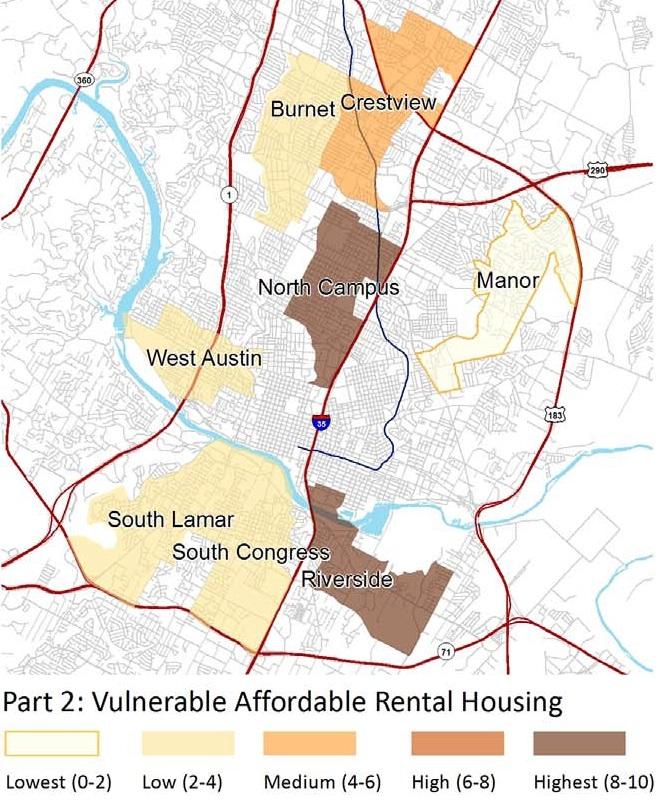

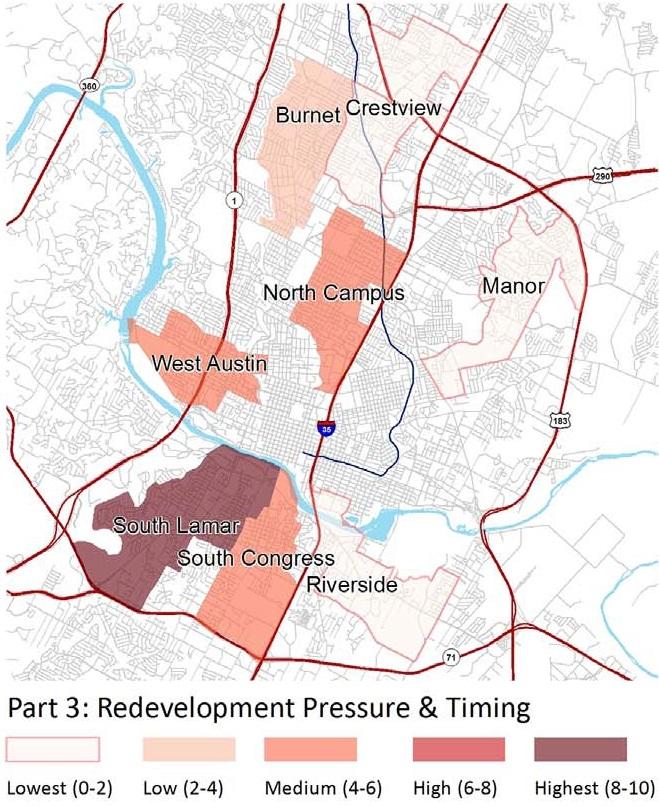

It’s been five years since you and your collaborators released Uprooted: Residential Displacement in Austin’s Gentrifying Neighborhoods and What Can Be Done About It, which included a toolkit with resources for addressing displacement. What is your assessment of the progress made since then?

I would say the results are mixed. There is certainly more attention paid to the issue, and the city itself recognizes that investments it makes will put additional redevelopment pressure on vulnerable neighborhoods. But we still lack resources and regulatory tools that can operate at the scale needed to really prevent displacement of those with the fewest options once displaced. And things are moving so fast that change has already happened across much of East Austin. Much of the work accomplished during and after the pandemic to raise awareness of the ease with which low-income people can lose their housing to eviction, and the challenges facing those who become homeless, is being undone. The recent bill pre-empting local authority in many areas of law makes it difficult to prevent evictions, to help tenants organize to improve conditions, to make it easier for them to use vouchers to pay for housing…the list goes on.

As a longtime observer of urban development in Austin and an active participant with the city on various issues, including housing affordability, you’ve seen Austin through many shifts and changes. What are some of the planning opportunities and challenges that lie ahead? What advice do you have for future planners as they work to address some of these issues locally?

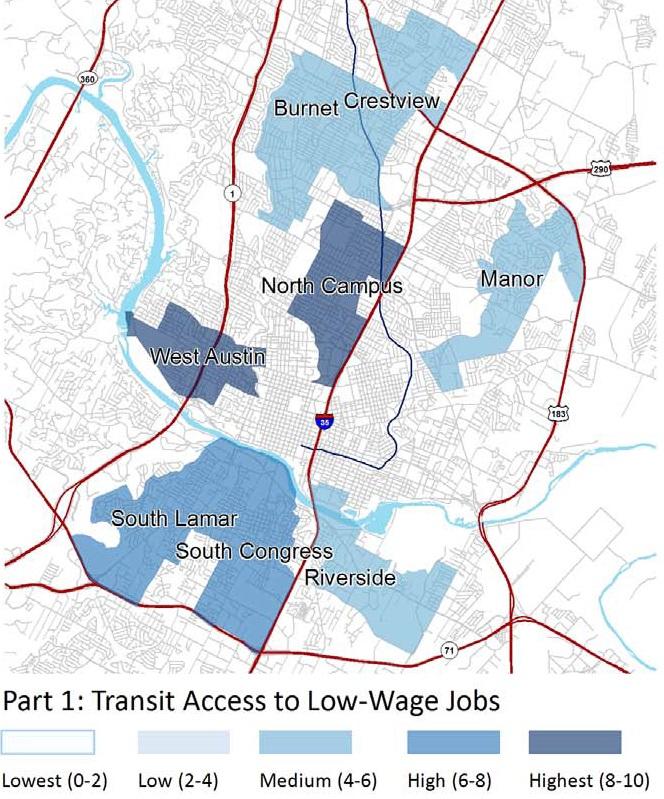

As planners we are being asked to plan and solve for multiple problems simultaneously: climate change and the increasing frequency of natural disasters, economic inequality, economic and racial segregation, housing affordability, and public health—to name the big ones. We understand better now how these issues are interconnected, but city governments are typically organized around discrete functional areas, making it difficult to think about and approach problems holistically. And this problem is compounded by conflicts between federal, state, and local levels of government and local politics. We are currently focused on using infrastructure investments to guide change, particularly transportation funds. But we struggle to integrate these big-picture goals into the planning process—and to act quickly.

All of these efforts will be overlaid on the existing social fabric of the city. To avoid deepening existing patterns of inequity—as we have during our sustained population boom—we need to bring a historical perspective to public conversations about these problems and lay out the likely consequences of various forms of action or inaction. Public conversation has become so polarized that we end up paralyzed, with many seeing their best course of action as just blocking whatever is being proposed. Our big challenge is to break through this impasse and have productive conversations linked to realistic steps toward solving these problems.

In terms of housing, I see a great need to create a significant stock of housing that is protected from the speculative market--what is called social housing elsewhere. Most of what we call affordable housing in this country is produced by incentivizing investment in housing for low- and moderate-income people through the tax code. This means that what we produce and who is served is largely constrained by the value of these incentives. The power of market actors focused on using incentives is strong, and the voices and experiences of those most in need of stable and secure housing are largely invisible in this system, which is dominated by those with the technical knowledge to navigate the complexities of using tax incentives and financing development. There are definitely groups going beyond the requirements of this system and doing a good job with their projects, but the larger picture is that this system is poorly matched to the needs of those struggling the most to live in decent housing in safe neighborhoods. This is a very long-term project but necessary to achieve real progress in providing housing security for low-income people.