Q&A with Professor Dean Almy

Dean Almy is the Program Director for the Graduate Program in Urban Design at The University of Texas at Austin, where he has directed the Texas Urban Futures Laboratory and worked as a Principal Investigator and Research Fellow at the Center for Sustainable Development.

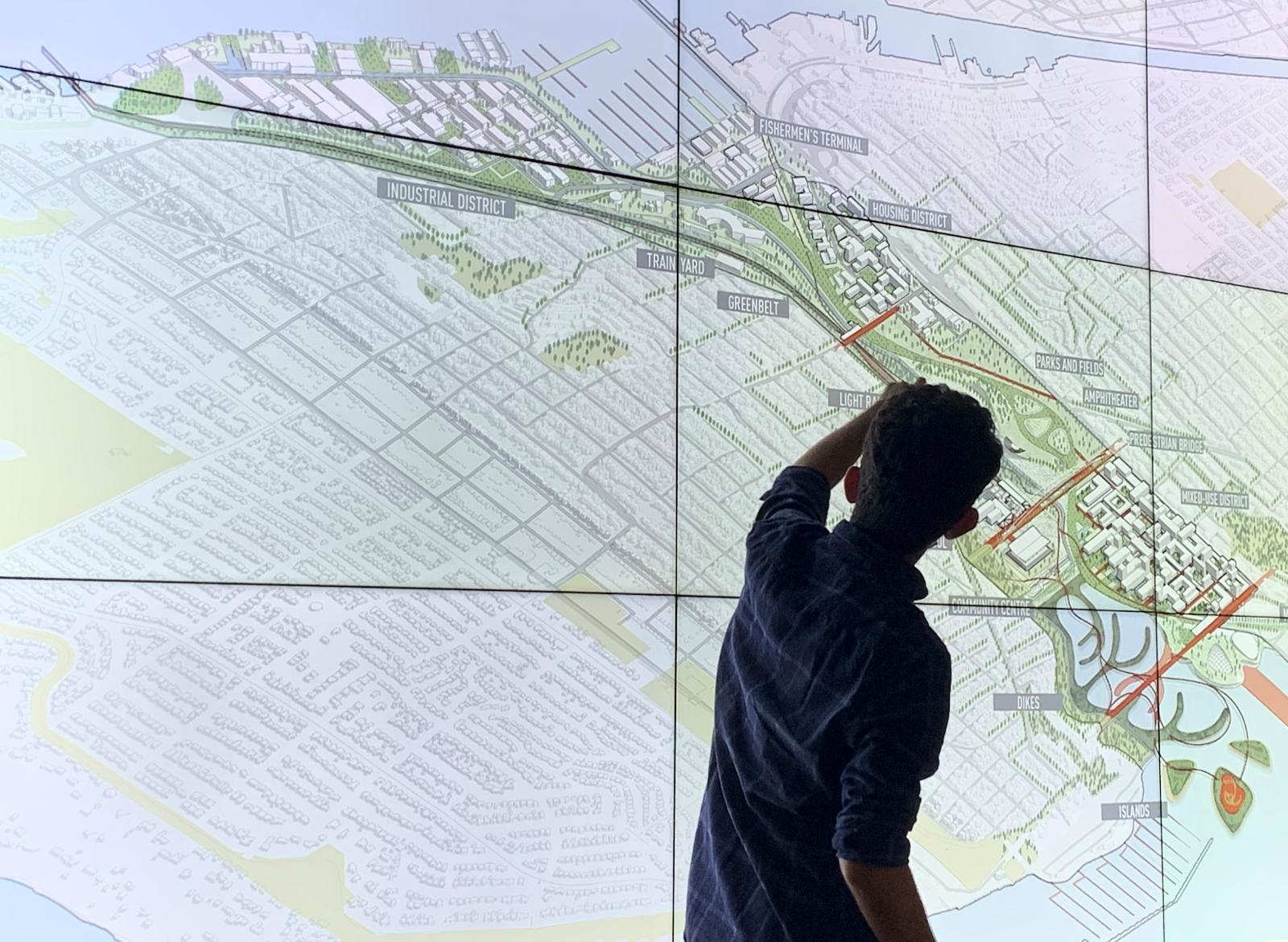

Professor Almy’s research and scholarship employ the creative practices of urban design to ask questions, re-frame issues, test spatial strategies, visualize scenarios, and serve as a platform for public advocacy in making better cities. At the school, he has led interdisciplinary research teams on multiple funded urban design projects including, scenarios for the future of Austin’s southeast quadrant and the associated Austin Convention Center expansion, and development scenarios for the South Central Waterfront.

A recipient of the Thomas Jefferson Prize for creative and scholarly research from the University of Tennessee for his research on urban design and urban housing, Professor Almy’s work has also received an AIA/RUDAT award for excellence in urban design, a 2009 Great Places Planning Award from EDRA and Places, and an American Planning Association, Sustainable Communities Division, Award for Excellence in Sustainability. He has also formerly held positions as: Director of the Graduate Program in Landscape Architecture, Chair of the City of Austin’s Design Commission, Vice-Chair of the Waterfront Planning Board, and founding Chair of the Texas Society of Architects, Urban Design Committee.

---

In recent years, you've dedicated energy to bringing urban design academics, practitioners, and theoreticians from around the country together for conversations about the future of urban design education and the discipline as a whole. I'm thinking, particularly, of the Climate of Urban Design Symposium you organized right before the pandemic. Why is this type of coalition-building and future-looking conversation necessary?

Urban Design is a field that has been at a crossroads for some time. The issues urban designers are dealing with have never been more complex or more pressing. Humanity is facing serious questions about the structure and performance of our urban environments, the impacts of climate change, adaptation, sustainability, and resilience. A lot of essential work is being done across multiple disciplines: architecture, landscape architecture, planning, real estate, etc. Each has a claim over some aspect of urban design's agency. There are also distinct differences between how urban design is taught and practiced, not only between disciplines but also within them. Faculty working in this area at institutions around the country are frequently isolated and are routinely lone advocates for a discipline often considered a specialization within other fields. There are limited opportunities for building an academic cohort within a single institution and few opportunities for discourse between faculty at different universities. Establishing an association of faculty across the country that will strengthen the discipline and be a forum for exchanging ideas on pedagogy, research, and practice is crucial if urban design is to gain currency as a discipline in its own right, with its histories, theories, and practices. Our former dean once stated that to have interdisciplinarity, one first had to have a discipline. I agree with that.

The conference focused on the relationship between the academy and the profession as agents for addressing climate change. Separately, I also convened twenty academic heads of urban design programs nationwide. We were interested in the climate of teaching urban design at our various institutions. This effort exposed a robust latent demand for a stronger culture for the urban design discipline. Faculty at all stages of their career-long for more interaction with each other around these issues, and the younger generation also need a network of mentors to help them be successful. All this has led to the formation of the Urban Design Academic Council. The UDAC emerged from that first meeting in Texas before the pandemic and a few subsequent national conferences we have held since. Over forty-five faculty at institutions nationwide have joined the initiative, and we have a steering committee representing nine universities. We intend to expand the depth and reach of the discipline and strengthen linkages across allied fields. We also aspire to the creation of a national body, not unlike CELA or ACADIA.

In your introduction to Urban Agencies—Projections for the Contemporary City, you talk about how you hope the urban design program can establish a "new transdisciplinary alchemy" within the school. Could you talk a bit about this, and why this type of cross-disciplinary collaboration is so important?

Alchemy is one of those words that is part science and part magic. Aspirations of "trans-disciplinarity" are a bit like that too. Urban environments are too complex to be determined through a single discipline. Since urban design's agency is synthetic, it relies on accumulated knowledge, often generated from within other fields, and applies it projectively. Urban design asks questions like, what if? To investigate such questions, one also needs to understand; what has been, what is, and how might we get there? Answers to these questions often come from the research and practices generated by allied disciplines. Urban design can test the integration and application of this knowledge.

There is a spirit of knowledge production across the school that aspires to be collaborative; we just have to operationalize it better. We don't have time to be dogmatic about it. There are significant problems to solve, and we need all the perspectives we can get. Such an agenda may require rethinking the values and mission of the field, the role of urban design as an internationally focused graduate program, and how to best leverage the resources of our faculty and our institution to make an impact. One must value the diversity of perspectives here at the school and, perhaps, in so doing, arrive at unanticipated solutions.

Tell us about the significance of the applied research work you've led, or that's coming out of the urban design program.

Three strands have primarily guided the research, both my own and what the urban design program sponsors. The first has emerged from my role as a research fellow at the Center for Sustainable Development. The CSD has been an invaluable resource for the school and me. It has been a mechanism for supporting the applied research I engage in. There are several projects I have worked on through the CSD, all have been collaborative, and all use the synthetic nature of urban design to visualize the resultant spatial impacts of development while presenting the implications, socio-cultural, financial, etc. Perhaps the most visible of these projects has been the work done for the Austin city council on the convention center's future and what the consequences of various scenarios would be on central Austin. A second strand focuses on supporting students in their research. The program provides funding for students to publish honors-level research in urbanism, a program that has resulted in two recent books. This has helped to put the program in the larger global conversation on urban futures. Finally, we have been working with international partners such as Gehl to get our program to engage with cities' most pressing problems.

You've been at the School of Architecture for quite some time and in different capacities as a student and a faculty member. What are some ways the school has changed throughout your time here?

I came to Austin originally thanks to some former "Texas Rangers" with whom I had studied as an undergraduate. Subsequently, I was a post-professional student here in the late 1980s when urban design was still an unrecognized architectural specialization. I pursued my academic career teaching at various universities before returning in 2000. In many ways, little has changed, studio culture is still central to design education, but the issues we ask our students to address are much more complex: environmentally, socially, technologically, etc. The expectations we have for students are significantly higher as well. The school is also much more diverse now than historically, which is a positive change. We expect students to develop and work from an ethical foundation and to pursue their disciplinary accomplishments rigorously. Technological advances are changing how our professions work and our expectations for what we can accomplish. While the culture of architectural production is changing, so is the world. Students graduating now are entering a completely different world, and the involvement of the design professions in stewarding the change is even more critical now than it has been in the past.