Redrawing Connections: Design Advocacy in Section

The success of landscape projects is dependent on complex ecological processes from the sky through the soil, such as the flows of water and nutrients, space for roots in healthy soil, and actions of land care and use by human and nonhuman species. These relationships are not typically visible in plan or perspective drawings, but can be synthesized through explorations in section. Section drawings demand that we grapple with the complexity of dynamic conditions and, when employed as part of a critical design practice, can reveal the consequences of outdated and problematic policies and methods that do not serve the future needs of our environments. As designers working within this complexity it behooves us to embrace the politics of our work and advocate for changes in the way we build and care for our environment.

Advocacy requires that we shift our focus from the future form of an individual site to working in partnership with the individuals and organizations engaged on the ground and policymakers working at the scale of the city. Landscape architects can contribute to their efforts through tools of visualization and insight into the ecological processes that support the environment. As landscape scholar Rob Holmes notes, “Before landscape problems can be analyzed and solved, they must be framed. Solutionism short-circuits this crucial step in the design process.” By engaging more deeply with the politics and processes surrounding our work, landscape architects will be better positioned to offer our perspective on how to frame the problems we are helping to address. And by working in section, we will be better able uncover and illustrate the dynamic conditions we are working to frame.)

Over the last two years, I have led an advanced studio that engages landscape design as a critical practice through which to explore how changes in policy and on-the-ground practice can contribute to the shape of physical environments and the quality of life of those who inhabit them. This approach was piloted in response to the Landscape Architecture Foundation’s Green New Deal Superstudio, an initiative engaging a national conversation centered on design’s role in advancing justice, jobs, and decarbonization—the core principles of H.R. Res. 109/S. Res. 59, known as the Green New Deal. The Superstudio called upon designers and planners to engage the abstract economic and political strategies of the Green New Deal by exploring the opportunities it might offer for transformations of the built environment, with local specificity.

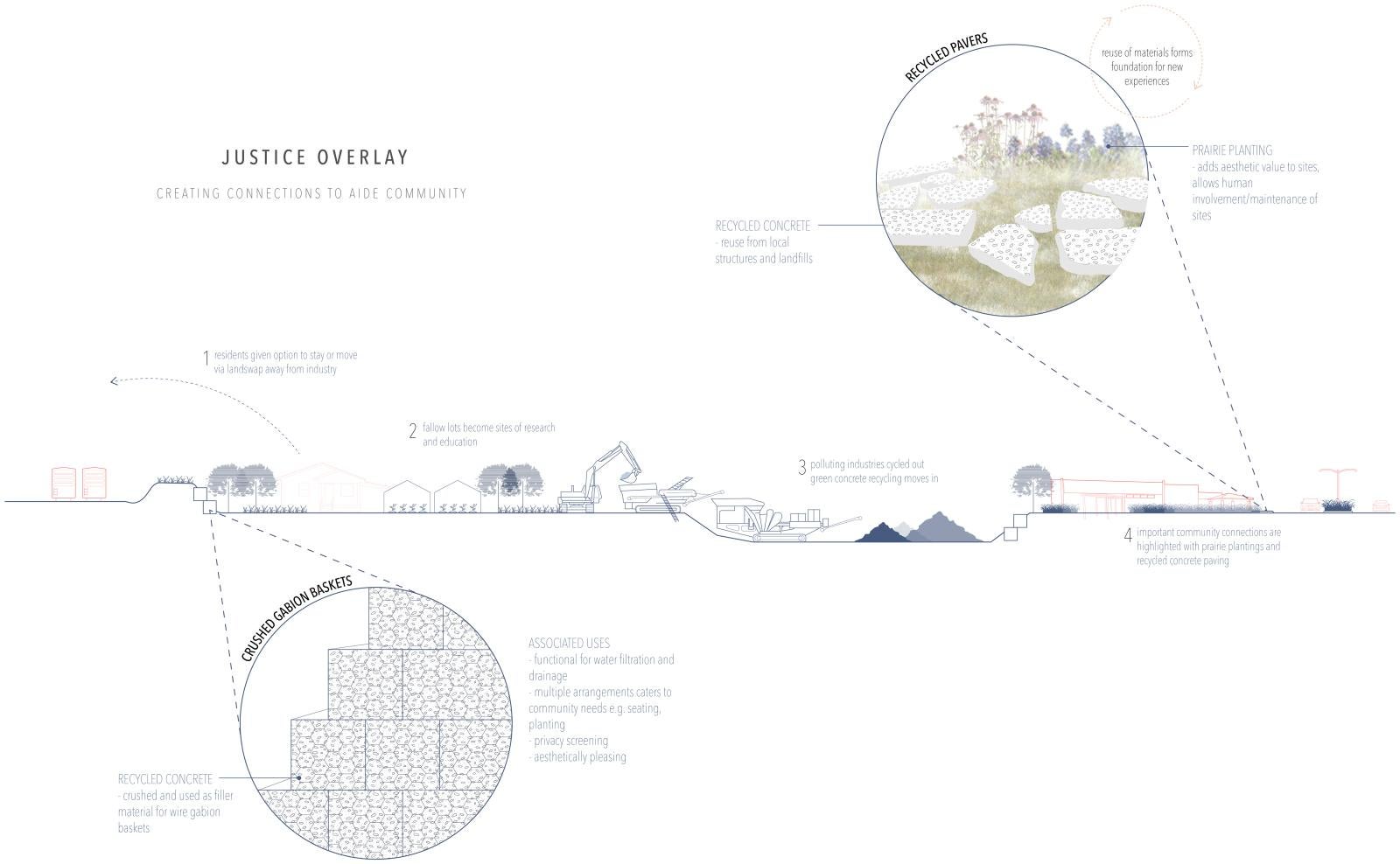

The agenda of the Superstudio aligns well with the attributes and requirements of the subject of my course, the Blackland Prairie ecoregion, a temperate grassland in Texas named for its rich, dark soil, and shaped by a long history of management through fire and grazing. Due to urbanization and agriculture, this tallgrass prairie is the most endangered large ecosystem in North America—less than 1 percent of it remains, and in fragmented remnants. Tallgrass prairies offer a variety of environmental services: pollinator habitat, water filtration and retention, and carbon sequestration. Prairies are also spaces of incredible beauty with seasonal flowers, rustling grasses, and varied textures. The prairie’s beauty and environmental performance can make powerful contributions to supporting environmental justice initiatives by helping to clean up pollution and slow urban stormwater, while creating a visual signal of beneficial change.

Recent landscape projects in the Dallas area have brought the beauty of the prairie back to the city: recalling its form and palette (Harold Simmons Park, the Master Plan for Fair Park, George W. Bush Presidential Library), restoring its ecological relationships (Trinity River Audubon Center), or preserving a remnant prairie (Clymer Meadows). While prairie plants do not require extensive resources in terms of irrigation and fertilizing, each of these projects’ approaches to creating and maintaining a prairie landscape require extensive and ongoing human actions to prevent encroachment by woody and invasive species. As a part of my ongoing research on design through land care, I have focused my studio on considering how human actions of maintenance and care can contribute to strengthening social connections within communities, creating economic opportunities through new jobs and industries, and recovering deeper relationships with our environment.

Like most advanced landscape studios, our work begins through a process of design research developed by mapping—first as a process of exploration, then as definition, and finally as speculation. These diagrams often begin as planimetric overlays of information from GIS data. At the metropolitan and regional scale, seeing the signatures of topography overlaid with infrastructure or flood lines against so-called “open space” reveals an underlying logic of settlement patterns as well as the persistent impacts of planning policies over time.

Our understanding of Dallas is animated through discussions focused on its ecology, its prehistoric Native American presence, its modern planning history, and contemporary efforts to create public amenities within the Trinity River corridor and movements in support of environmental justice.

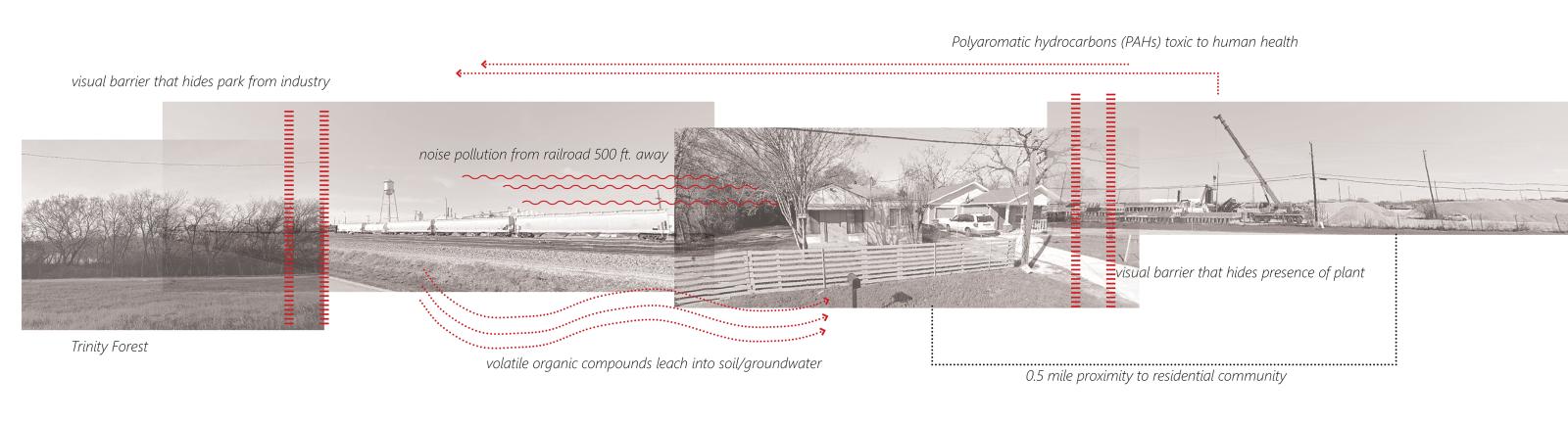

Past and present inequities are embedded in Dallas’s urban fabric, perpetuating a disparity of experiences across the city. Neighborhoods of incredible wealth and opportunity are within one mile of neighborhoods shaped by policies that allowed pollution near homes and streets without curbs and gutters. Many communities lack public park spaces in which to gather, play, and be immersed in vegetation, while underutilized parcels form an urban patchwork. Working in plan, we can guess about the impacts on the land and the inhabitants living alongside industrial machinery and scrap yards and bounded by highway ramps—but plan drawings remain abstractions of relationships on the ground.

To understand the experience and qualities of a place, we need the sensory data of physical experience of place alongside the knowledge of those who have encountered it on a regular basis. This is not a community-engaged design studio, but it supports many of the skills of community-based work through repeated discussions with a range of experts from Dallas, who are each committed to shaping the city’s future. The studio’s arc and content have been developed in dialogue with two Dallas-based designers from Studio Outside, Isaac Cohen and Gwen Cohen, who contribute their perspective as design professionals in the city, as well as their ongoing research on the Blackland Prairie as an ecoregion with particular social histories and ecological qualities. Throughout the semester, Isaac and Gwen provide the studio with a grounding in place, adding depth to what we could piece together from photos alone in 2021, and from our time on site in 2022.

As the intertwined impacts of the legacy of racist zoning, inconsistent regulation enforcement, and incompatible uses become clear, we work through visualizations of these invisible forces that shape everyday life. Our studies are informed by the ongoing policy work of Downwinders at Risk and Southern Sector Rising, two community-based organizations working on behalf of Dallas residents to implement policies against industrial pollution. Students build on graphic advocacy techniques used by designers at Interboro and the Center for Urban Pedagogy, who often use very simple line drawings and cartoons to demystify the role of public policy in the built environment. We also work from the more speculative and art-based techniques used by landscape architect Julie Bargmann to reveal that spaces often described as vacant, marginal, or open might better be described as wild or fallow. While vacant lands are thought of as available for development or empty, fallow land suggests soil that is temporarily at rest. Like Bargmann, students use collage, hand drawing, annotation, and layered media to describe landscape spaces as full of ecological life, informal social uses, cultural histories, and latent processes awaiting activation.

Throughout the semester I encourage rapid iteration in section to consider relationships from sky through soil, with human and nonhuman actors animating small and large changes to the land. Drawing in section foregrounds relationships alongside the human experiences of a context’s edges. The results of these investigations as both site reading and initial concept range from a remembrance of loss of street life by Rachel Kadidlo (M. Arch ’23) to the more analytical representation of pollution flows and landscape edges developed by June Landenburger (MLA ’21).

Landscapes are in a constant state of change and emergence, shaped by human and nonhuman forces incrementally over time. Recently, landscape scholars and practitioners have called for a recovery of earlier models of design practice that embrace the actions of care that create and sustain landscape space. Landscape scholar, Julian Raxworthy identifies growth as the primary medium of landscape architecture, and calls for designers to engage actively in the labor of shaping space through gardening to better understand and connect with the living materials of our designs. In studio, I ask students to engage the actions and impacts of growth, change, planting, and decay through drawing critical moments in time. Again, working in section we can see how changes to one “layer” of space have associated impacts. For example, periodic mowing is necessary for a meadow to remove woody shrubs, but it also stimulates root development, increasing the capacity for water filtration and carbon sequestration.

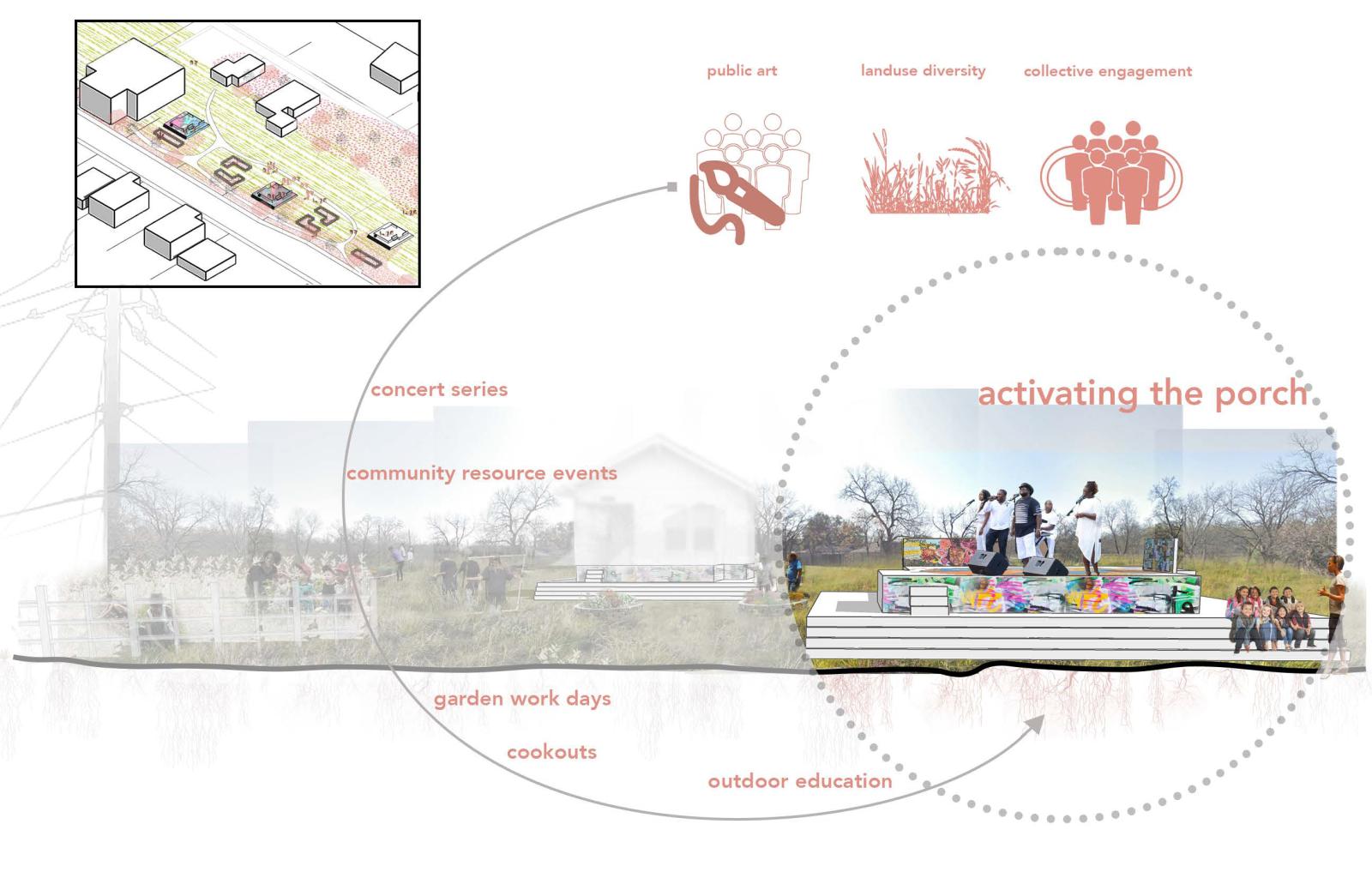

By drawing the process of installing and caring for a landscape over time, students are able to identify other opportunities to strengthen relationships, beyond ecological entanglements. Many students used the section studies as a way of recovering the lost social histories of a site through visualization. Taylor Davis (MLA ’21) created diagrams to document the seasonal actions of gardening and maintenance that sustained Black Freedmen’s communities in the bottomlands of Dallas. These studies informed a proposal that recovers the once thriving historically Black community in the Tenth Street Historic District through a process that begins with land care and gardening. In addition to the cultivation of parcels, Davis imagined events and initiatives that would document the history of the neighborhood and rebuild social fabric, inspired by the work of designers like buildingcommunityWORKSHOP and Paper Monuments.

Landscape architecture- and particularly landscape architecture in section - offers a way of seeing space not as a collection of objects, but as a set of dynamic relationships: the existing interconnections, and often the missing processes needed for a site and its inhabitants to flourish. My hope is for students to see design not just as a set of technical skills for making beautiful places (though this is important!) but as tools for understanding and then challenging the status quo—in form, policy, and process.

MAGGIE HANSEN >>

PLATFORM: TEACHING FOR NEXT >>