"Why Landscape First?" by Gullivar Shepard

Landscape is the medium between us and nature, often the means by which we reinvent our relationship to the planet. Elizabeth Kolbert’s somber accounting of humanity’s efforts to put the world back together in Under a White Sky underscores the desperate need for a large-scale reframing of our relationship with this medium:

“If there is to be an answer to the problem of control [of nature]—it’s going to be more control. Only now what’s got to be managed is not a nature that exists or is imagined to exist apart from the human. Instead, the new effort begins with a planet remade and spirals back on itself. Not so much the control of nature, as the control of the control of nature.” 1

The conference Landscape First: Unearthing the Benefits of Nature-Based Solutions directed attention to the rapid changes occurring in landscape architectural practice as a lens for reconsidering the business-as-usual development that currently shapes global cities. History shows us that forms of human settlement are often bluntly overlaid atop the undergirding geography of our planet, impacting the intricate networks formed by the surface flows, wind patterns, groundwater, soil biology, ecosystems, and so forth. “Landscape First” suggests that landscape architecture is uniquely positioned to understand and manage the cumulative impacts on environmental systems and, in turn, their effects on our own health and well-being.

While innovations in design sustainability put a spotlight on the creation of more visible and consumable products/projects for reduced impact—the ‘what’ we build—we have still not garnered a significant shift in the conventions of ‘how’ we build, ‘how’ we settle, ‘how’ we manage, or even ‘how’ we assess progress. These conventions are nestled quite deep within the bureaucracies and power structures in our world and hold a consequential share of cumulative impact. How we confront the historic ills of controlling nature requires an eyes-wide-open assessment of how much environmental function needs to be re-established to future-proof the health, safety, and well-being of our global cities. As a living medium, landscape is deeply connected to how nature is built, managed, and adapted in current practice, aligning our profession with this needed shift in how we build.

UNDERSTANDING THE STATUS QUO

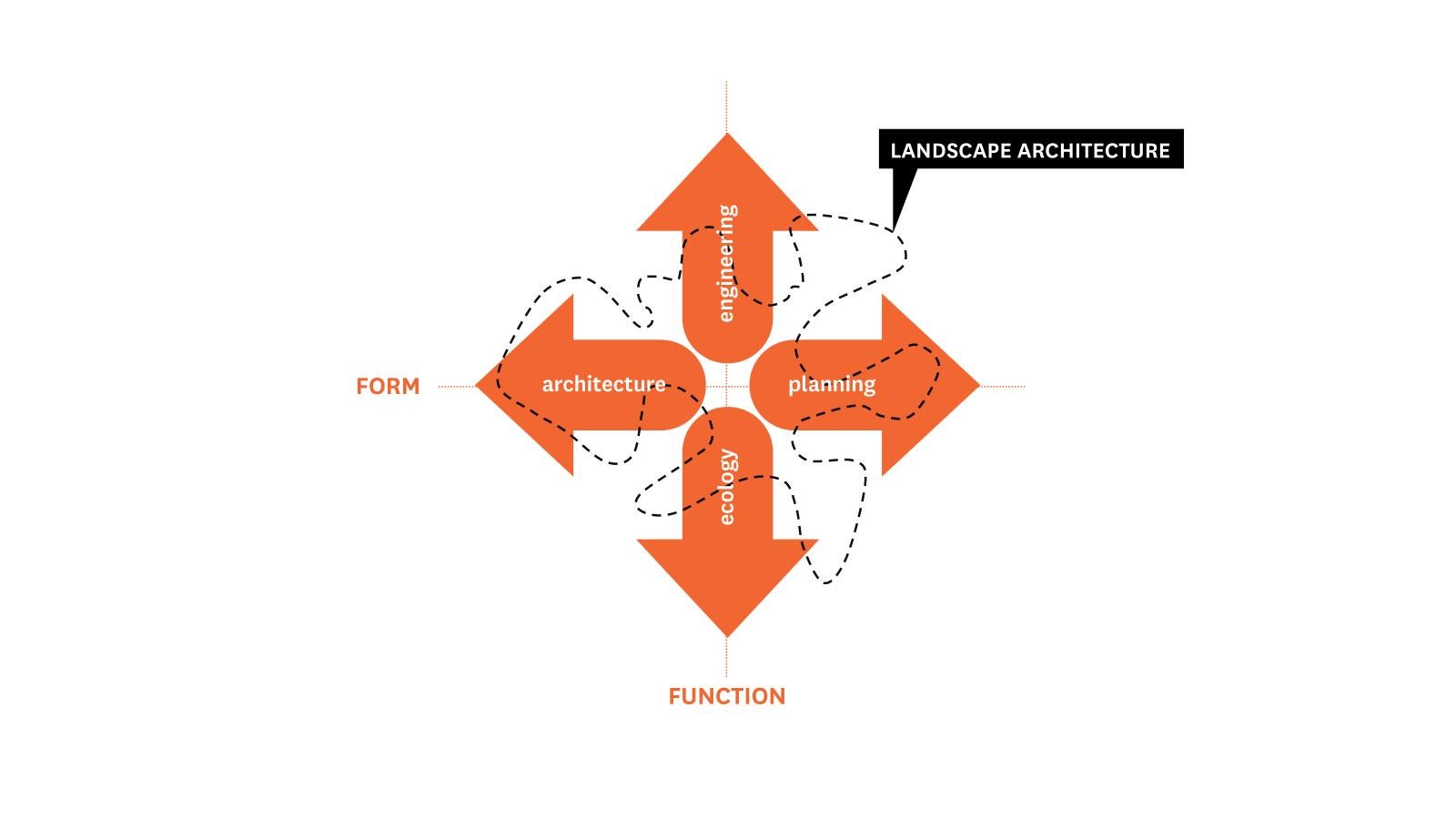

Four canonical professions have been traditionally far more synchronized to institutional and governmental decision-making than landscape architecture, each of which embodies siloes of influence that deeply shape our patterns of settlement: architecture, planning, engineering, ecology. These fields all issue from a decision-making center to define a matrix of human settlement. This framework maps form and function against localized and geographic scales, a crude but useful tool to examine the collateral impacts of each of the professional ‘products’ and the expanse of territory in which the landscape architect is often left to navigate:

Architect – focus on refining the form and syntax of the human settlement (localized scale) Urban Planner – focus on refining the geography of people’s spatial needs for human settlement (geographic scale)

Function:

Engineer – focus on delivering technical infrastructural solutions for human settlement (localized scale) Ecologist – focus on technical restoration of environmental function at the boundaries of human settlement (geographic scale)

The landscape architect often operates in between and around the work of all these professional actors across form, function, and a broad spectrum of scale. In many cases, the landscape architect attempts to herd the group of these canonical actors to better leverage their professional position outside of these siloes, integrating the beneficial ideas of each while reconciling the collateral impacts produced by the pursuit of individual goals.

WATERFRONTS FIRST

Landscape architecture’s peripheral role in recent urban design obscures the fact that the matter of building cities was central to the creation of the profession of landscape architecture in the United States. One only must look at the career of Frederick Law Olmsted to realize that the American discipline’s founders were zealous generalists, as invested in urban form and infrastructure as the pastoral escape. In fact, the earliest recorded evidence of Olmsted and Calvert Vaux adopting the title "Landscape Architect" was not for the design of Central Park in 1857—for which they were named "Architect-in-Chief" and "Consulting Architect"—but for the urban planning of northern Manhattan above 155th street three years later. Nearly 60 years later, Harvard University’s very first courses in city planning, taught by James Sturgis Pray, were introduced by the School of Landscape Architecture. It was not until the post-World War II rise of suburbia that “landscape” in America became more associated with exurban parks and gardens than with organizing cities.

Degraded urban waterfronts have been the catalyst for bringing landscape architects back into the heart of city-making. Over the course of the last 25 years, MVVA’s projects have been increasingly associated with addressing the lost function of geographic features that were brutally recast to serve the demands of industrialization. With the recession of the industrial “glacier,” a new paradigm for remaking the city was needed vis-à-vis the waterfront in particular—one that that was not simply answered within the core professional siloes of engineering, architecture, planning, or ecology. Rather than playing a background role, landscape architects stepped in to conduct these disciplines on waterfront projects not only to make challenging urban spaces more habitable, but to tactically reinsert natural function in degraded urban margins. The synthetic nature of this work adopts a worldview about rethinking the relationship of the city to the geography in which it sits: “leading with landscape.”

Building on this success, the professional is clawing back their relevance in the discourse around urban life. The field at large is undergoing tremendous changes in scope, perspective, and authority. Landscape architecture is a profession in a tremendous state of flux, demonstrated by a few trends:

• Extreme eclecticism in the ‘site’ of landscape interventions

• Growth of landscape-oriented products and technologies in the market

• Political efforts and activism concerned with the built environment

• Technologically enhanced modeling of environmental impacts

• New workflows and methodologies led by landscape architects

The value of this work has also gradually become less about public space as design iconography and more about building an environment as a staging ground for nature to renew its hold. While aesthetics are still key, the present-day urgency of climate-related impacts and the many health issues arising amidst urban populations has brought the public’s attention to see the value in weathered, dynamic, and even willfully untidy landscapes: adopting underutilized or compromised lands to establish stormwater parks, community trails through landfills that are being actively remediated, pollinator landscapes, and countless other opportunities. The rhetoric visible in these designed landscapes celebrate nature’s work-in-progress and are culturally becoming sites of collective optimism.

Landscape-architect led projects in Brooklyn, Toronto, and Austin, each set on complex and compromised urban waterways, illuminate the shifting role of the profession as a force in city-building—reoccupying, rebuilding, and reinventing how these natural forces, which are still at work, can coexist with the myriads of other urban systems. An important foothold for this work was MVVA’s practice of exploring regional waterways as analogues to help drive planting designs and inform how to adapt complicated, highly impacted and flood-prone sites to be more habitable and resilient. This analytic work doesn’t adopt pristine riparian landscapes as the target for restoration but instead learns from plant communities that perform within disturbed urban site conditions: landscapes where nature is actively rebuilding and sustaining the complex exchanges between land and water.

REOCCUPYING — BROOKLYN BRIDGE PARK, BROOKLYN, NY

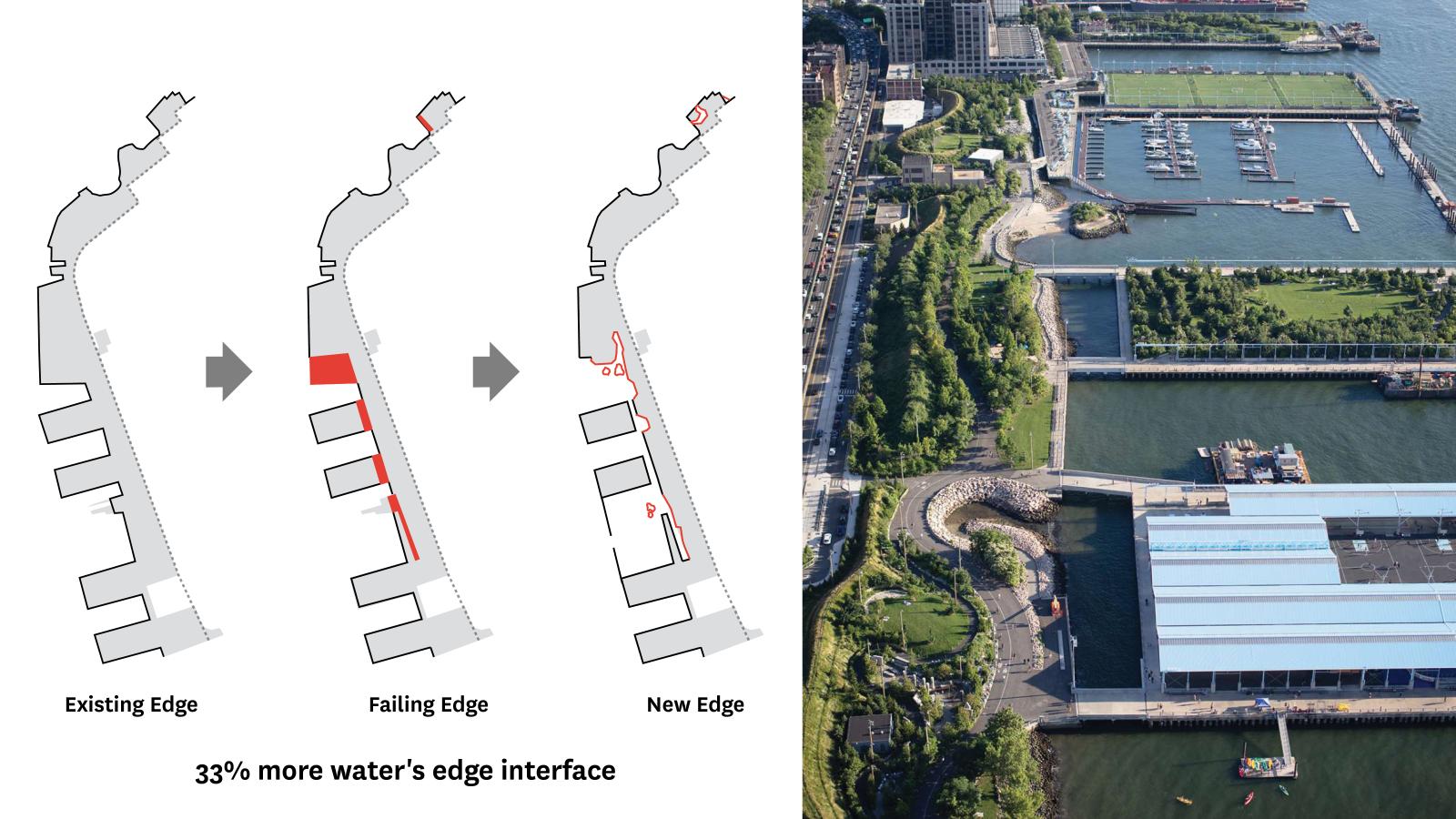

Across the East River from Manhattan’s iconic skyline, a Brooklyn cargo facility created a monolithic concrete and asphalt ground plane elevated on structure above the tidal zone. Left largely derelict for decades, this constructed water’s edge was quick to erode, with portions of the marine structure collapsing into the river. In fact, at the time of early park planning, most of the Brooklyn waterfront offered itself as a catalogue of “post-industrial nature” where decades of neglect revealed nature’s work to reestablish stability in the land-water interface on highly disturbed edges.

While the engineering assessment of these marine structures on the Brooklyn Bridge Park site clarified what should be removed and what should remain, the study of the post-industrial waterfront revealed opportunities for introducing new edge conditions where park users might be able to get closer to the water, delineating where the future landscape of the site could be fueled by renewed land-water interactions. The park design created variety and complexity along the water’s edge to foster new experiences for the community on the waterfront through beaches, stone banks, and boat launches, along with reintroduction of ecological function through salt marshes, floodplain ecosystems, coastal shrub zones, and upland topographies.

The complementary concept to this leveraging of the water’s interaction with the marine edge was to utilize all upland water sources to generate living systems. Transforming an artificially flat site through swells, steep escarpments, and swales reinterpreted pre-development landscape complexity and created spatial conceits for holding new park program. This new topography was simultaneously woven into a mosaic of environmental conditions for storing and conducting site runoff, slopes and aspect, drainage, soils, sunlight, and wind exposure—all of which allowed a rich variety of plant communities to thrive in niche areas throughout the park.

The project recreates powerful complexity along the water’s edge by intuitively building a resilient waterfront out of the observations of landscape materiality under urban stresses and utilizing interventions for new user experiences. Fostering these two conditions invited nature to reoccupy the land and better sustain regimes out of land/water interactions.

REBUILDING — PORT LANDS FLOOD PROTECTION, TORONTO, ONTARIO

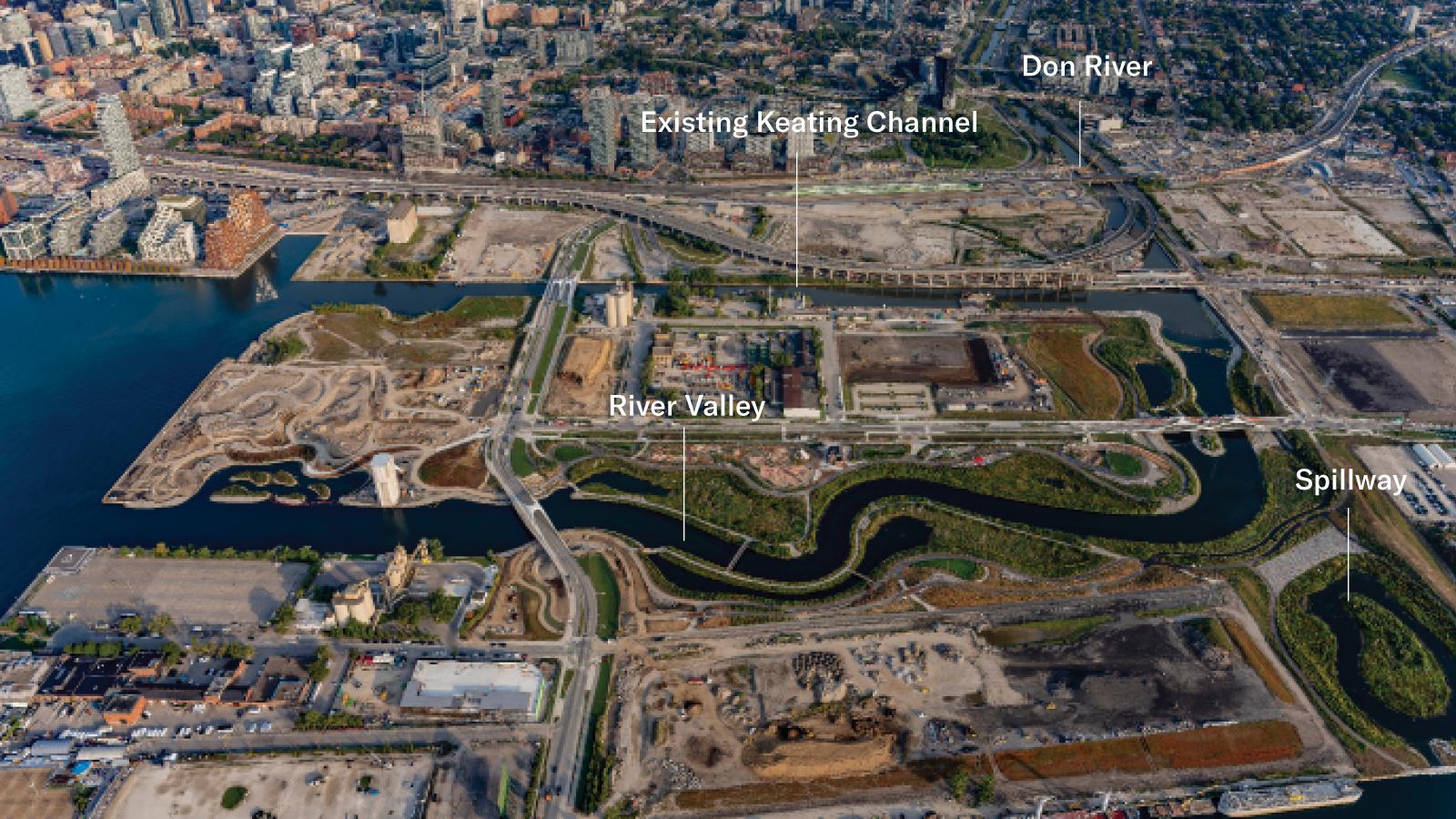

The Port Lands Flood Protection (PLFP) project is located where Toronto’s 38-kilometer-long Don River joins Lake Ontario at the former site of Ashbridges Bay Marsh, once one of the largest freshwater wetlands on the Great Lakes. At the beginning of the design process in 2008, there was no hint of that landscape: urban and industrial activity had severely degraded the aquatic ecosystem, the waters of the Don were redirected into the concrete-edged Keating Channel along an unnatural 90-degree dogleg, and the marsh was filled in to create the Port Lands: 400 hectares of paved industrial land. This constriction of the water placed 290 hectares of Downtown Toronto within the floodplain of the Don River, the danger of which became clear in 1954 when Hurricane Hazel triggered the worst flood in the city’s history. This substantial risk led Waterfront Toronto, a public-partnership between municipal, provincial, and federal governments, to remake the Port Lands.

The construction of the new mouth of the Don, completed in 2025, has introduced a three-pronged flood conveyance system including the existing industrial channel, a new naturalized river mouth channel, and a landscaped spillway. This has removed three-square kilometers of the waterfront from the 100-year floodplain. Not only was it utterly impractical to reinstate the pre-urban Toronto marsh because of massive real estate costs, ground contamination, and critical city infrastructure, there was also a collective realization that a river mouth is a landscape type that does not exist within the recorded history of the world without human settlement. These challenges again reflect the impossibility of restoration, and the project was aimed at how to rebuild ecological and hydrological function—not in a perfect world, but in a highly impacted and highly urbanized site.

A macro-evaluation of North American river morphology and micro-observations of nearby disturbed river mouth areas helped establish a calibrated understanding of the meander geometry and topographic conditions that help slow water velocity and encourage sediment deposition. Beyond an intuitive application of these discrete, exaggerated moments of natural systems, hydrological modeling advanced the application of these observations into predictive models for flood behavior, shear stresses, scour, and sediment deposition.

The project “leads with landscape,” building out from deep ground improvements, invented-hydrological flow regimes, catalytic constructions that build habitat capacity and ecological diversity. This core work of the new river valley now affords a variety of public space opportunities and becomes the anchor for 52 hectares of future city-building activity structured by the urban planning and infrastructure development of a complete community, including a full complement of transportation systems that rewire this new district into the fabric of the downtown Toronto.

REINVENTING — WATERLOO GREENWAY, AUSTIN, TEXAS

Waller Creek’s long history of flooding in Austin’s downtown reflects a familiar story of stormflow impacts and patchwork engineering solutions that escalate with the growth of the city. By the early 21st century, this creek landscape was in a state of constant disturbance and collapse with signs of geotechnical slope failures that would soon impact adjacent properties. In 2018, the City of Austin implemented a radical solution to downtown flooding: a 1.5-mile-long tunnel bored deeply below the watercourse, bypassing the downtown area and directing the creek’s stormflow directly into Lady Bird Lake. This removed more than 28 acres of the most valuable property in downtown from the creek’s floodplain, paving the way for millions of square feet of creek-adjacent redevelopment.

While the tunnel project mitigated the disproportionate stormflow pressure on the shrinking creek landscape, it left behind a deeply-incised watercourse with steep bank conditions and a litany of utility and easement challenges at its edges with no real plan for what to do with the existing landscape. Would this creek become even more urbanized with time, or find an alternate path to reinvent itself? A budding conservancy got its foot in the door with the promise of transforming this Gordian knot of technical challenges and oddball urban circumstance into a unique public space opportunity.

The project balances many entangled roles: as stormwater infrastructure, an armature for a new district, a much-needed boost to urban tree canopy, a mobility corridor, an anchoring civic space for community functions, a collection of tertiary infrastructure functions linked to the adjacent development, and a reintroduction of a resilient ecosystem. The resulting Waterloo Greenway serves as a unifying hybrid program that pushes beyond any conceit of restoration, embracing the freedom to completely reinvent the idea of an urban creek in the context of explosive growth and 21st century urbanism.

The reinvention of Waller Creek operates at the scale of the city by being highly responsive to an eclectic collection of adjacent developments, city-scaled infrastructure, and cultural circumstances, such as a new light-rail station, a rebuilt convention center, new addresses for existing cultural institutions, historic parks and structures, and construction of the tallest building in Texas. Small gathering spaces and a chain of parks serve as activity bridges that animate the passage into a new creek channel landscape and help mediate scalar transitions from these massive city-building projects along its edges.

Traditional restoration approaches typically lay back creek slopes to simulate the riparian edges of undeveloped waterways. This convention had virtually no applicability for a creek that had to remain deeply incised within steep bank conditions and support hundreds of interfaces with city infrastructures. Instead, the project restores through a collection of novel approaches that support fluvial communities, catalyze biological activity at the water’s edge, and match the syntax of urban interfaces with tactics for novel habitat creation. One of the projects iconic identifiers is an embankment assembly that simultaneously stabilizes failed slopes and allows nature to take hold in the friable and unstable surfaces of cut blocks of caliche—a waste product of the limestone quarry industry typically cast aside due to the same weak material qualities that allow it to host ecology. By incorporating site drainage to seep water, the stepped assemblies capture sediment and seed flotsam, leaning the blocks to direct and retain moisture. These assemblies have already begun to recolonize the edges on the banks of Waller Creek and build continuity between the upper and lower banks.

THE SPIRAL

Perhaps the arc of the landscape architecture profession is, in fact, tracing work that “begins with a planet remade and spirals back on itself,” as Elizabeth Kolbert has described other similar efforts to restore a semblance of natural functions. But it is a beginning, and one that requires rigorous focus on what the planet intrinsically is: the geographies that undergird our settlements, the hidden cycles of water and air, the intelligence of soil. How to make these powerful subtleties of the environment understandable and vital is an immensely complicated question that the landscape architect struggles with every day—each decision creates a potential “butterfly effect,” in which small changes in these nearly invisible conditions can create significantly different outcomes over time and space.

Notes

1. Elizabeth Kolbert, Under a White Sky: The Nature of the Future (New York: Crown, 2021), 8.

Gullivar Shepard is recognized for his skill in navigating programmatic requirements, regulatory and jurisdictional hurdles, and problematic site conditions to create rich public spaces. With a background in architecture, his expertise ranges from the fine details of building landscapes to planning and managing the firm’s large, complex urban projects. These qualities bring an expanded interdisciplinary perspective to MVVA’s leadership. Since he joined the firm in 1999, he has applied his integrated design approach to challenges such as ecological restoration, flood control, transportation planning, and choreographing connections to parks and waterfronts. Gullivar always aims to tease out powerful design solutions within the constraints of a site by employing explorations of innovative building methods, communication tools, and project management.

Since 2013, Gullivar has led the planning and design of a 2.5-mile long greenway along Waller Creek in downtown Austin, Texas. The first phase, Waterloo Park, opened in 2021, with Phase II—The Confluence—scheduled to open in June 2026. In addition to Waterloo Greenway, he has led multiple planning and design efforts for the University of Texas at Austin campus.

This article is part of a series of essays exploring topics inspired by “Landscape First” hosted at The University of Texas at Austin in the spring of 2025 with the generous support of the Still Water Foundation. All opinions, views, and provocations expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the official positions, policies, or perspectives of the School of Architecture.

READ THE ENTIRE LANDSCAPE FIRST ESSAY SERIES HERE →