If buildings were invisible, what of architecture would remain?

Designing for the blind and visually impaired offers a unique perspective on the built environment that is valuable for architects and architecture students who strive to become better, more inclusive designers. A recent comprehensive studio taught by School of Architecture alumni Claire Townley (M.Arch ‘19) and T. Andrew Stone (M.Arch ‘18) asked students to design a new building for the Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired (or TSBVI), challenging them to transform their thinking about the spatial experience and to investigate architecture from the perspective of those who cannot see it.

Recently, a project from that studio designed by Anisha Kamat (B.Arch ‘23) and Lillian Giraud (B.Arch / Architectural Engineering ‘24) was recognized with a Student Honor Award from the Dallas Chapter of the American Institute of Architects’ 2023 Built, Unbuilt, and Student Design Awards. Given annually, the AIA Dallas Student Design Awards seek to recognize the most innovative and thoughtful student work from the architectural programs that have historically supplied talent to AIA Dallas member firms.

Operating as a special public school, TSBVI serves as a statewide resource for Texas children aged 6 through 22 who are blind, visually impaired, or deafblind, along with their parents and the professionals who serve them. Throughout the semester, the studio worked with TSBVI staff, who advised them on the project and program for the studio, hosted students on campus for several visits, and even came to the School of Architecture to lead cane training.

“We quickly learned that blind and visually impaired persons are ultra-engaged with the built environment,” studio instructor Claire Townley said. “They are truly an architect’s ideal client—taking in material changes, remembering one building from the next, engaging with the landscape, threshold, and cues; ideas that we celebrate in school and the profession.”

In collaboration with TSBVI staff, including a School of Architecture alum Gian Calaci (M.Arch ‘10), now program coordinator at TSBVI, the studio learned some of the incredible techniques and tools people with visual impairments use to navigate the built environment. These include human echolocation, which involves making snapping or clicking sounds to reflect off nearby objects and indicate obstructions, tuning in to auditory clues like wind chimes and the sound of running water that can signal boundaries or changes in the environment, and noting changes in temperature as a way to indicate a sense of space.

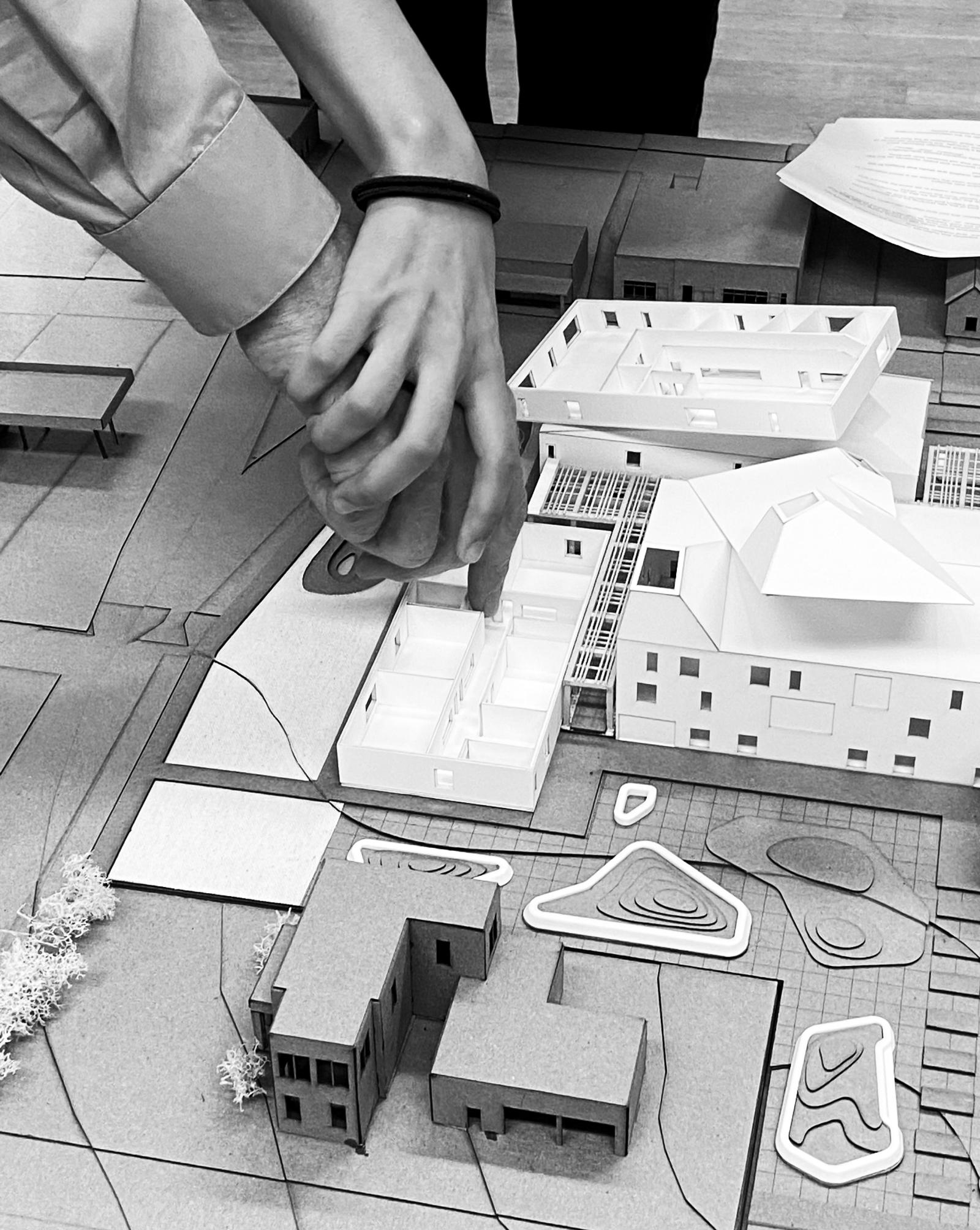

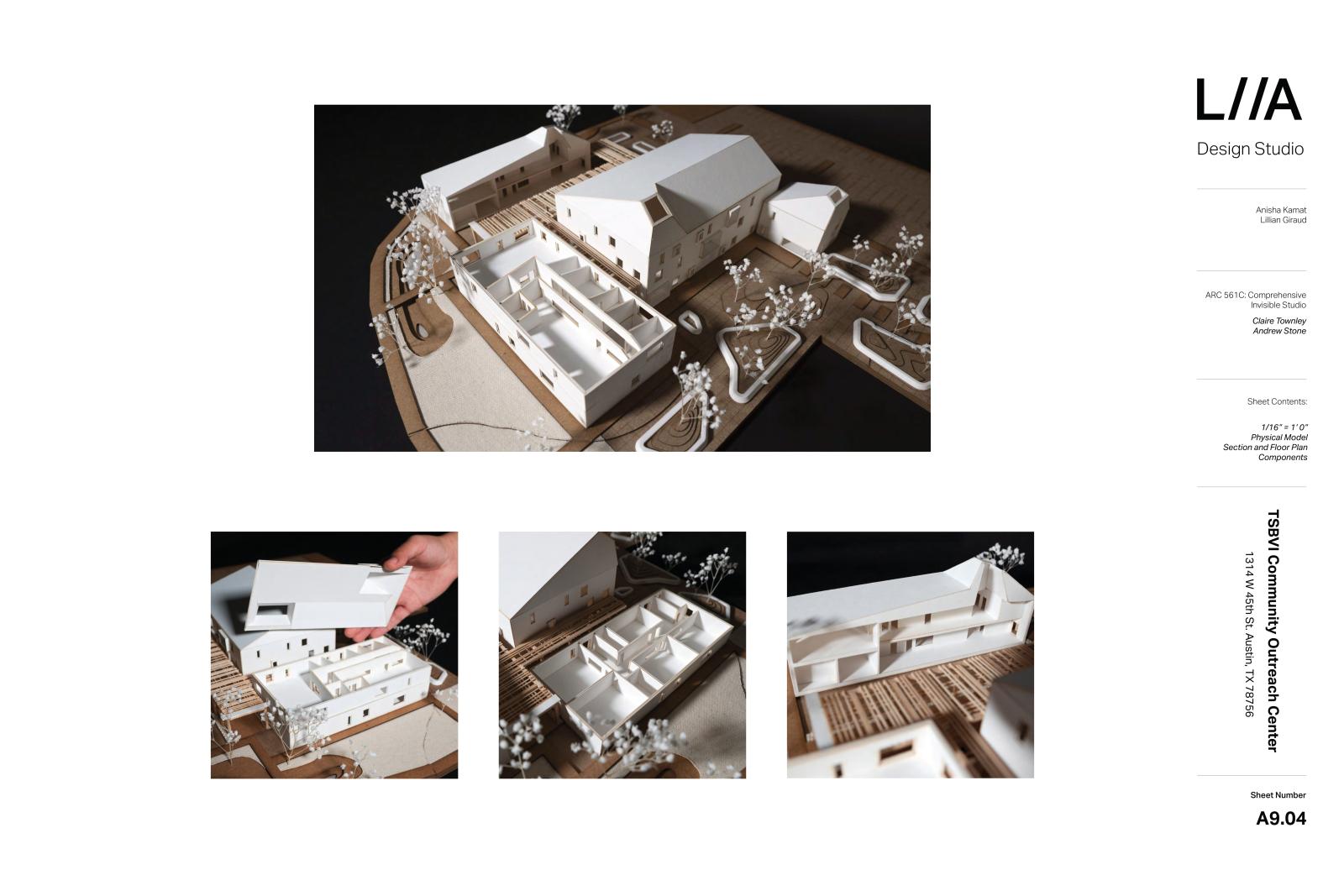

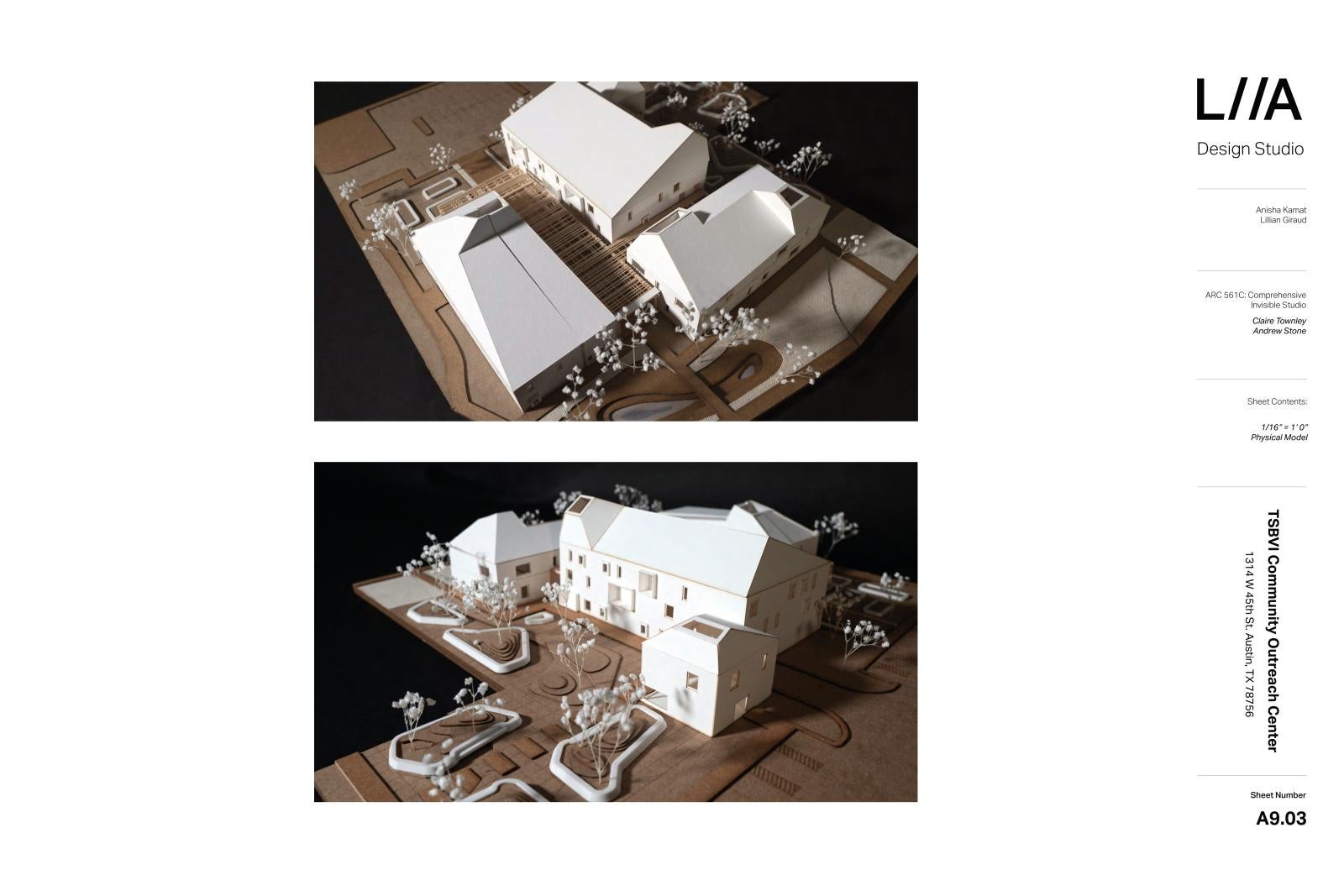

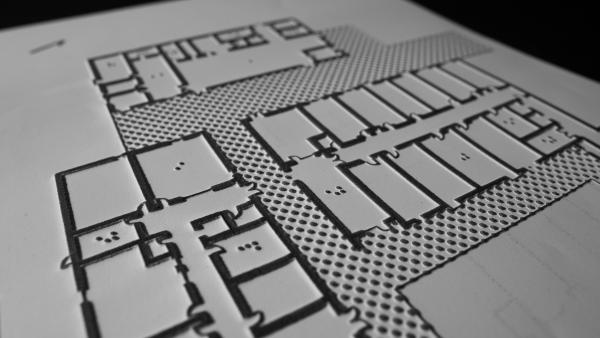

In addition to engaging a multitude of senses in their final project designs, throughout the semester, coursework encouraged students to experiment with innovative means of tactile expression. Relief drawings, physical model making, material palettes, audio recordings, and verbal communication complemented and expanded students’ design vocabulary, and their ability to have discussions with visually impaired clients. Students also used 3D printers, laser cutters, and the school’s woodshop to experiment with tactile drawings—a key method of communication. They also produced highly detailed and textured models in preparation for conversations with visually impaired individuals, including felt, sandpaper, wood, chipboard, mesh, and more to communicate design intent.

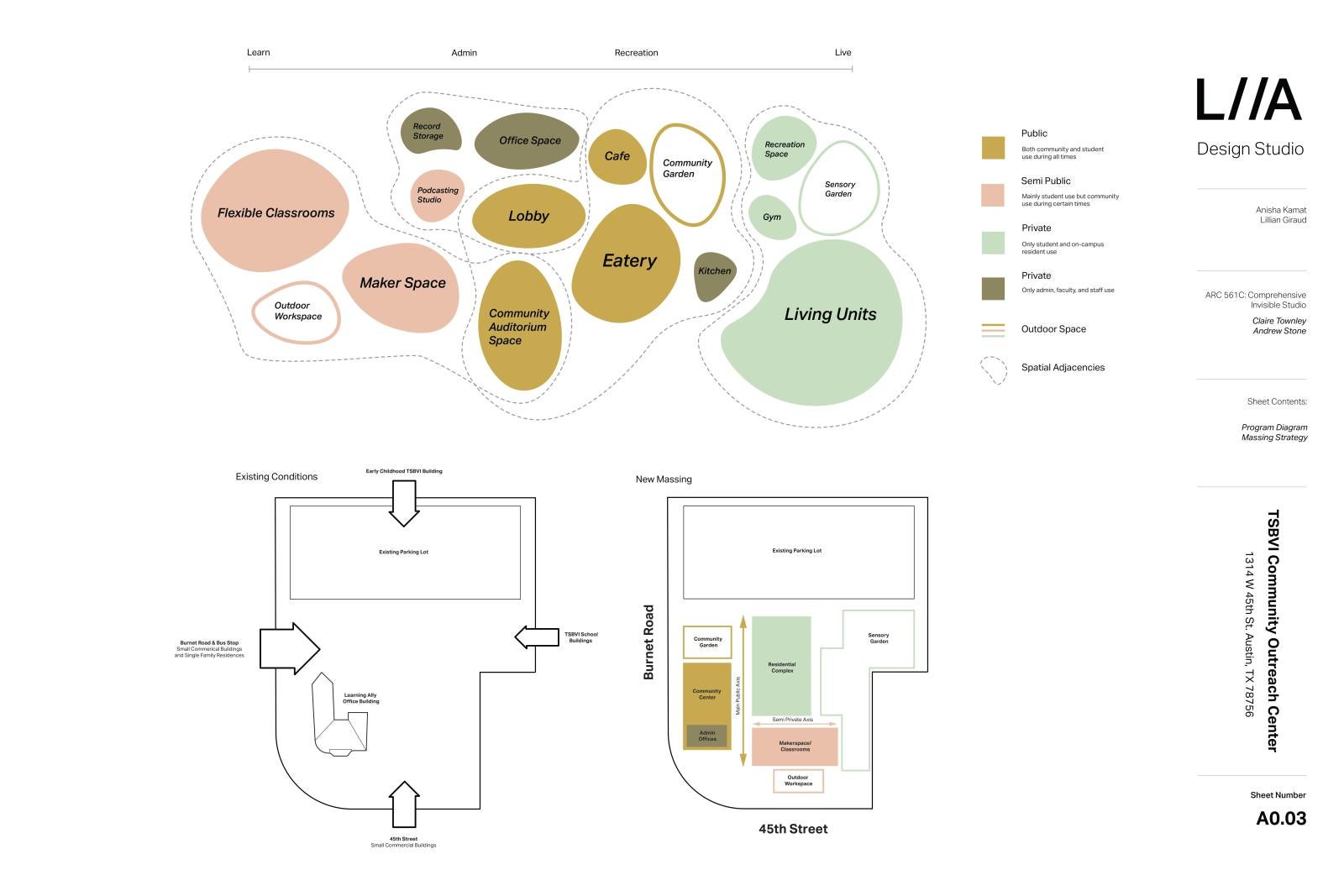

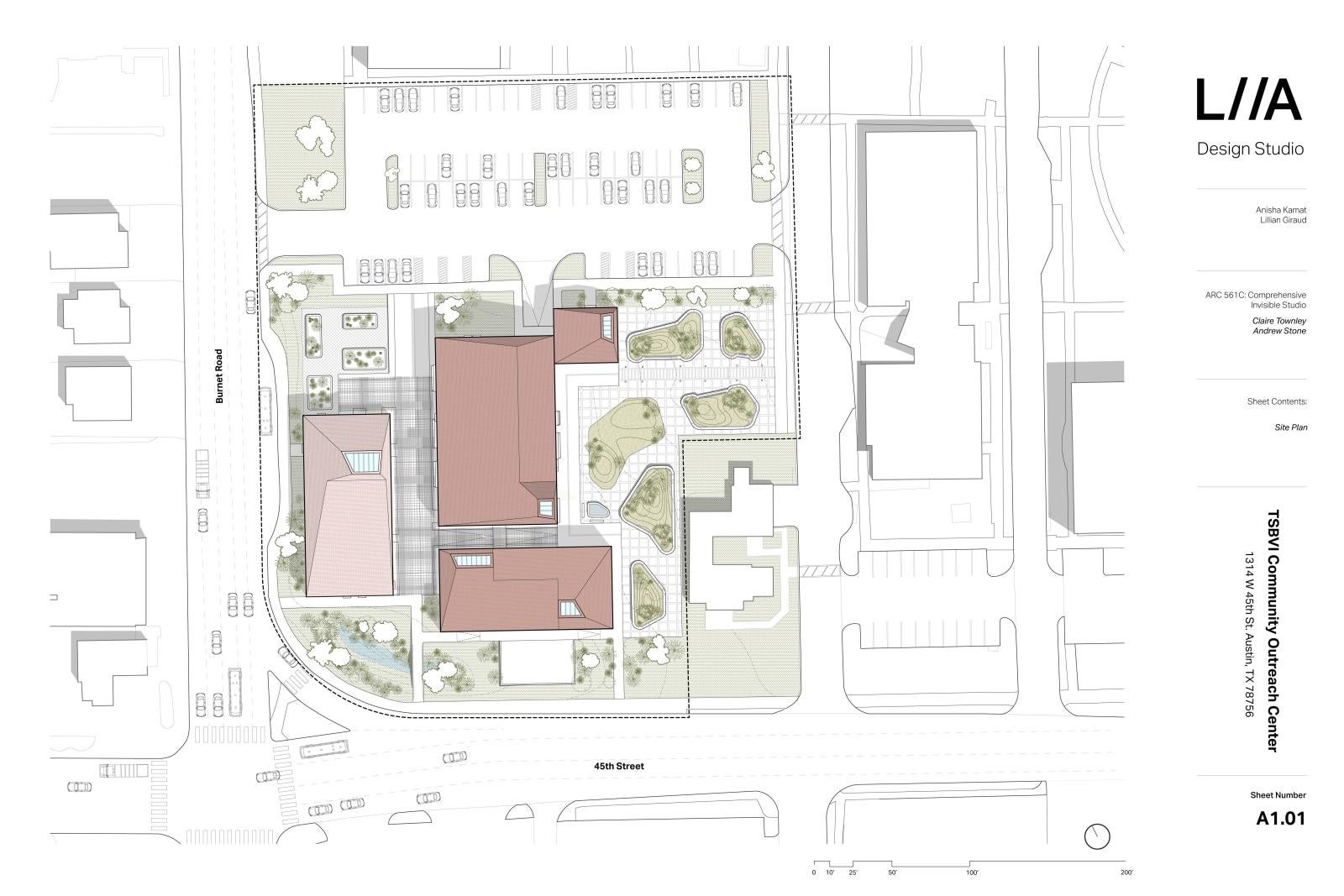

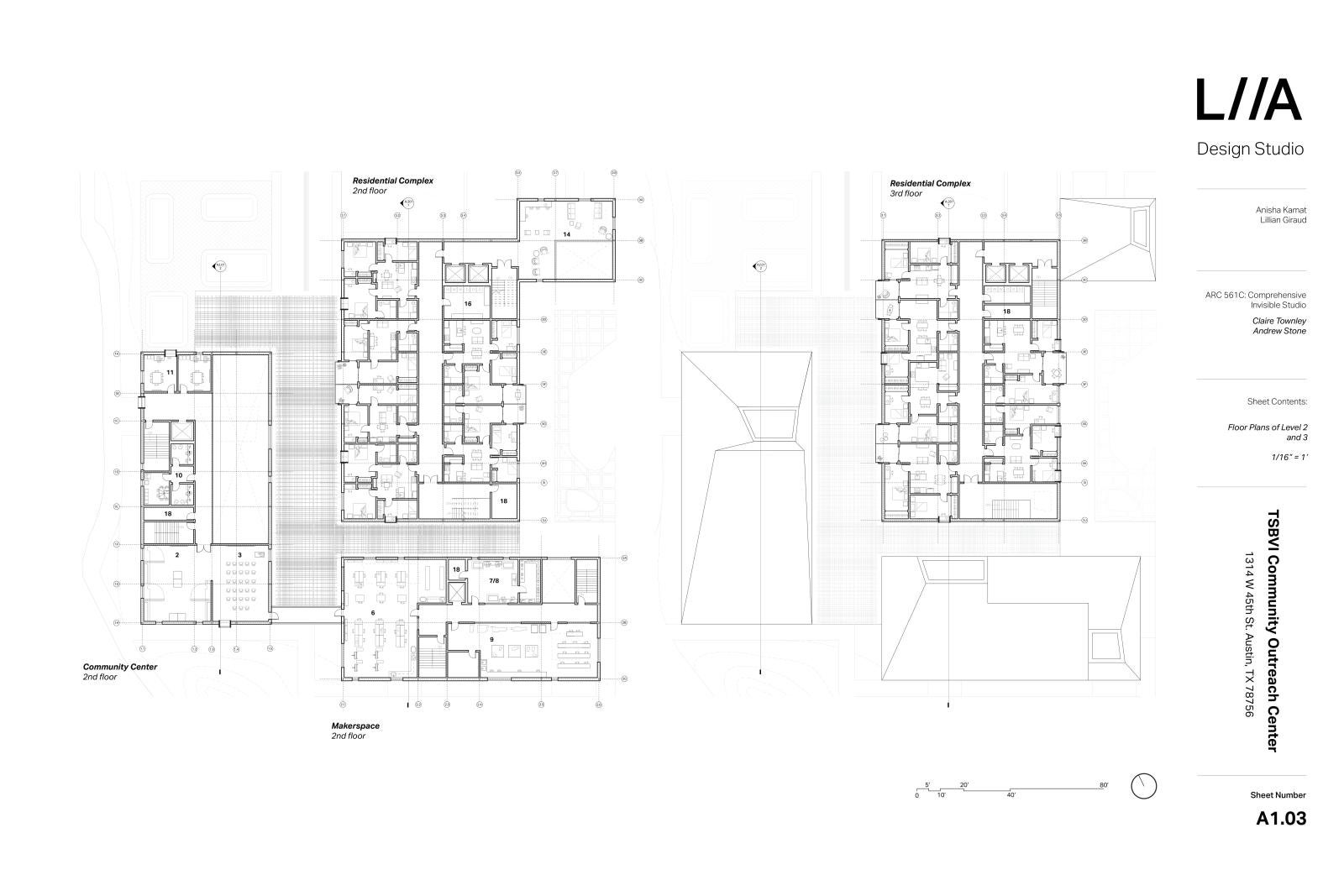

At the end of the semester, students presented their final projects: A proposal for a site located on the northeast corner of 45th Street and Burnet Road—an underutilized corner of TSBVI’s campus with the exciting potential to increase the school’s presence in a prominent and rapidly changing area of the city. The project’s program—developed in conjunction with school representatives—included apartments for TSBVI students, faculty, and staff, and publicly available units as a means of revenue generation for the school. The building also included a maker space, technology lab, podcasting studios, and classrooms.

As part of their final review, students presented their designs to critics, including renowned blind architect Chris Downey.

“Something that we realized very quickly is that the visually impaired experience necessitates the intellectual creation of a whole by piecing together discrete experiences,” studio instructor T. Andrew Stone said. In typical reviews, architecture is communicated nearly exclusively visually. Plans, sections, elevations, perspectives, and even models, give an easily digestible visual overview that can be quickly cross-referenced and understood by looking at multiple drawings at once. The visually impaired, on the other hand, must deduce this information piece by piece from individual parts. “They have to build the understanding of the space in their mind from the pieces they can feel, which is much more in line with how architecture is experienced in real life. Moving through a space, our brain builds a continuous experience by piecing together parts. This perspective, tied directly to human spatial experience, is acutely needed in the field of architecture.”

As Chris Downey reminded everyone during the studios’ final review, the job of an architect is not to produce images or to represent “cool looking” buildings but rather to engage in the intellectual exercise of designing spaces versatile enough for everyone.

For more information about the studio, watch a recording of Townley and Stone’s Spring 2023 CAAD Forum and read on for Anisha Kamat and Lillian Giraud’s AIA Dallas award-winning project.

Located in northwest Austin between Lamar Boulevard and Burnet Road, the Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired (TSBVI) is a statewide resource for students (6-22) who are blind, visually impaired, or deafblind, along with their parents and the professionals who serve them.

The school’s integral mission is to prepare students from an early age to transition into independent lives upon graduation by empowering them with access to specialized learning tools classes, and recreational activities. Some of these include podcast studios, an on-campus library that houses tactical symbol maps, accessible teaching kitchens, and the adjacent Sunshine Garden, which hosts planting workshops. The chosen site for this intervention sits on the very edge of campus at the corner of Burnet, an important transit corridor, and 45th. The surrounding site context consists of mainly single-family residential with smaller commercial and office spaces along Burnet. Despite the pedestrian-friendly program directly adjacent to the school, much of the site is inaccessible for those with visual impairments due to the noisy street conditions, lack of planting barriers, and curb cuts.

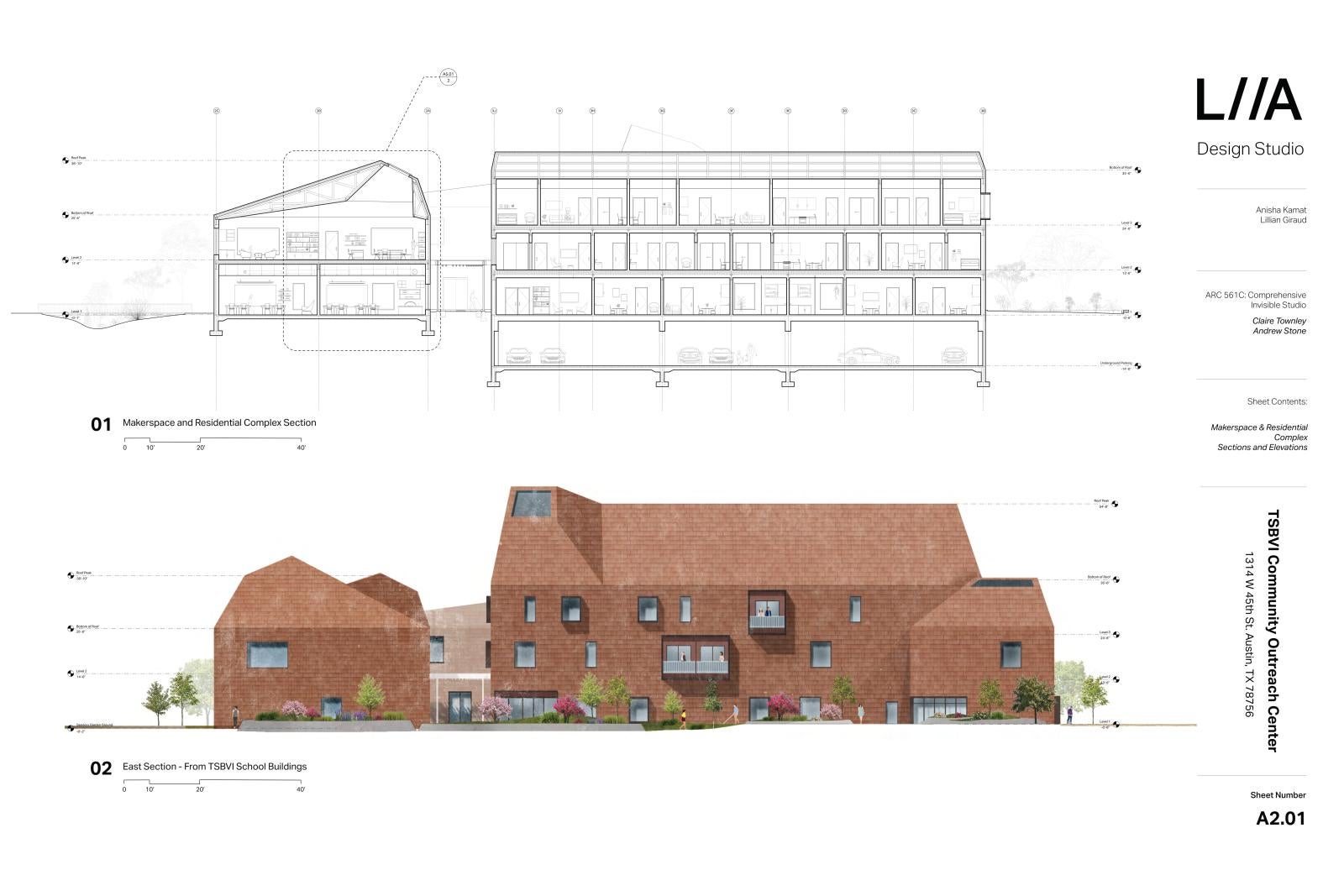

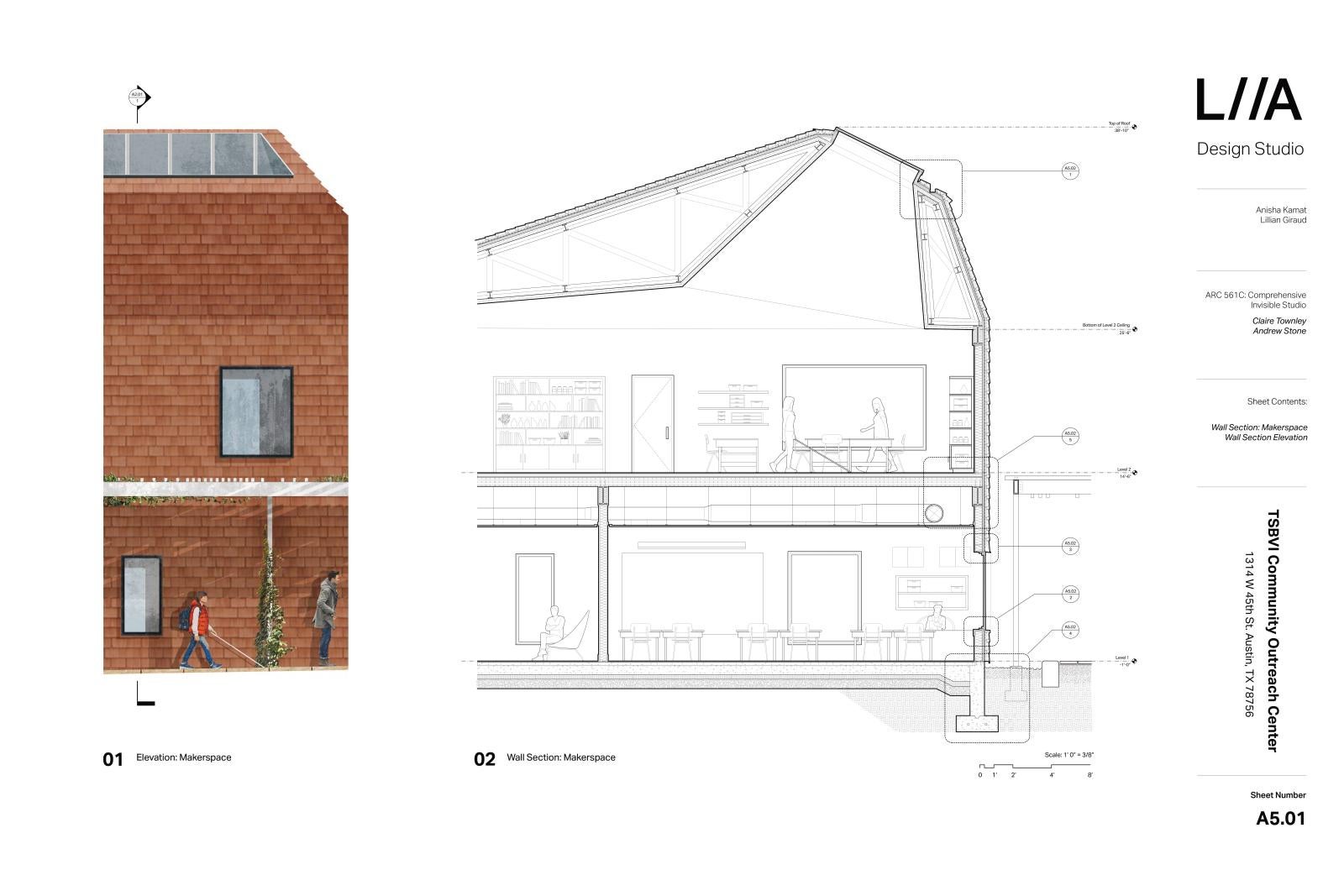

To address the noisy street and quieter campus conditions on each edge of the site, the main programs, a community center, a maker space, and a residential complex, are separated into distinct buildings to create a mini campus-like environment. This site strategy allows for primary and secondary circulation axes between buildings that protect from street noise and traffic while embracing the exterior environment. The massing scheme of separate buildings accommodates a public-facing community center and a more private maker space and residential complex to create a hierarchy between the different uses. Consequently, the interstitial outdoor spaces formed between the buildings and site edges, a vegetable garden, classroom patio, and sensory garden encourage visitors and students to explore the natural landscape and healthy living in different ways.

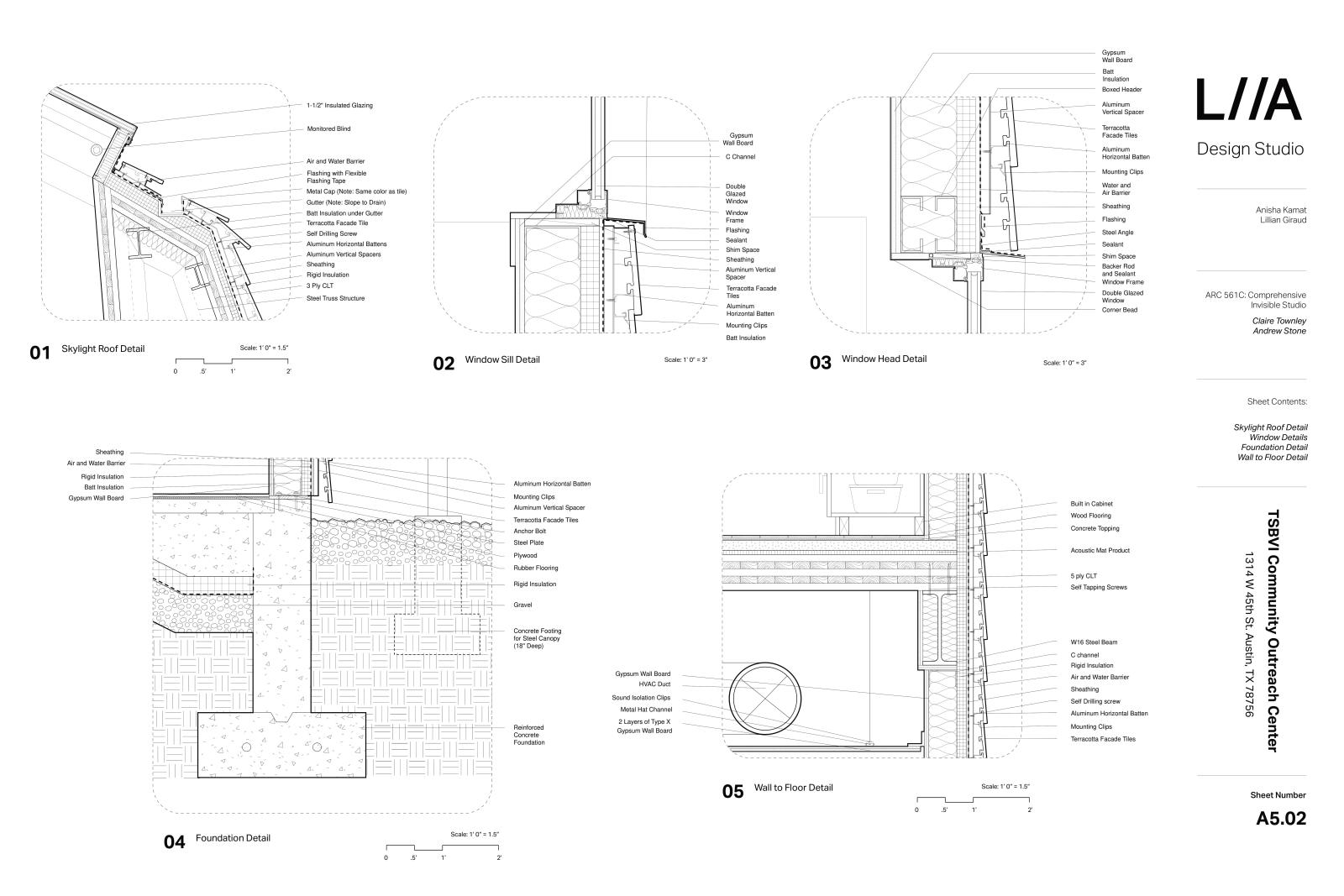

A critical aspect of this studio was to research and implement universal design strategies that aid with wayfinding, placemaking, and wellness for blind and visually impaired students. Through discussions with the mobility instructors, site visits, blind navigation training exercises, and architectural precedent research, we developed exterior and interior design strategies to address these unique user needs in an accessible yet playful manner.

Each building uses skylights to allow for expressive forms while preserving the easily navigable floor plan. On the exterior, they create a playful aesthetic language by sharing the elevation of the roof. On the interior, the skylights introduce natural light and warmth into the social interaction spaces, highlighting distinct public programs.