Mapping the Jaguar Corridor: A Radiography of Urbanization

To put a place “on the map” raises many questions. Maps have often been instrumental in conquest and colonization processes, but they can also be powerful artifacts that ignite dissenting ways of seeing and reimagining our world. The map of the Jaguar Corridor might be an example of the latter. This landscape project envisages the creation of a continuous territory covering 4.5 million square kilometers (half the size of the continental US) stretching from northern Mexico to northern Argentina to ensure the survival of the jaguar (Panthera onca). Borrowing landscape architect and theorist James Corner’s terms, I consider this map as both a finding—an acknowledgment of the need to cultivate and care for a series of landscapes to prevent the extinction of the Americas’ largest feline and top terrestrial predator—and a founding—because it compels us to radically question the colonial capitalist modes of inhabitation that have led to environmental breakdown and the sixth mass extinction.

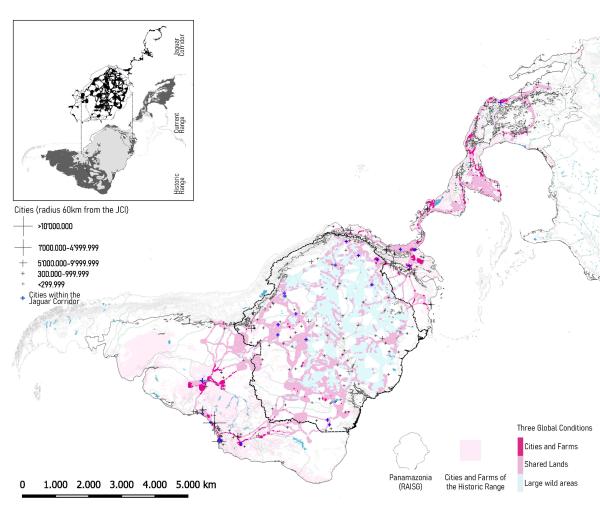

The Jaguar Corridor Initiative was launched in 2000 and is led by the New York-based conservation organization Panthera. The initiative goes well beyond the conservation of the jaguar. Researchers regard the feline’s presence in a territory a measurement of the health of an ecosystem; an indicator of animal and vegetation diversity, as well as water and air quality. So far, the corridor has remained largely under the radar of urban and landscape architecture researchers, even though urbanization processes are deeply entangled with this aspiration of hemispheric integration. The most viable habitats for the jaguar are proportionally inverse to those linked to extended processes of urbanization. Aside from elevation (jaguars mostly live under two thousand meters above sea level), conditions such as cover type, percentage of tree and shrub cover, distance to roads, as well as distance to human settlements and areas of high population density are all determining factors in the presence or absence of this feline.

In a years-long research project supported by the Graham Foundation (2020), I have developed a cartography of interconnection that makes visible the entanglements and frictions between the processes of urbanization and the Jaguar Corridor. This has involved correlating the corridor with public data about the transformations and socio-environmental struggles that are symptomatic of urbanization processes. The research has prompted a series of seminars I have taught both at The University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture and at Universidad de Los Andes, in Bogota, Colombia, in which students choose a theme through which to research, analyze, and visualize the complex processes of urban transformation intersecting with the corridor. In this essay, I introduce the Jaguar Corridor mapping initiative and reflect on the collaborative project of the School of Architecture students who participated in my spring 2023 seminar focused on tourism.

The Jaguar Corridor provides us with a radiography of urbanization—one that challenges a city-centric view of the urban experience. Urban political ecologists Maria Kaika and Eric Swyngedouw describe urbanization as the “history of urbanizing nature”—a socio-spatial process of capitalism that unevenly incorporates, transforms, and commodifies all types of nature to support urban life over increasingly larger and geographically dispersed territories. Through the lens of the cartography of interconnection, the Jaguar Corridor emerges both as a stronghold against these extended processes of urbanization—while nevertheless connected to urban life—and a contested territory in friction with the socio-ecological flows of these processes.

Conservation efforts to protect the jaguar emerged during the mid-1960s when the fashion craze for spotted cat skins from wealthy industrialized countries reduced the feline to a highly valuable commodity. After the massive killing of over 180,000 jaguars in less than two decades within the Brazilian Amazon alone, Latin American governments forbade trade and signed the 1975 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. Protection has meant stricter regulation, but not a complete end to trading. However, the main driver of jaguar population decline has been extensive habitat degradation, fragmentation, and loss driven by the expansion of agriculture, cattle ranching, and human infrastructures.

The region has been mostly urbanized from its southern and northern extremes—where most landscape connectivity areas are at risk of fragmentation. This is precisely what needs to be reversed, as the initiative seeks to foster the ecologically distinct jaguar populations across its entire range to ensure genetic diversity and the survival of the species. The Amazon is the largest remaining habitat for the jaguar. By 1900, the Amazon encompassed less than half of the jaguar’s historic range. At present, it accounts for almost 80% of Panthera’s Jaguar Corridor. Still, many towns and cities overlap with the corridor and need to acknowledge that in their public policy and municipal plans. Around 87 million people live within 60 kilometers of the corridor in at least 213 cities and towns. Half of those cities and towns are located within the Amazon region, comprising a population of more than 10 million. Additionally, close to 4 million people live within the corridor in around 27 settlements, each with populations of up to 1 million inhabitants.

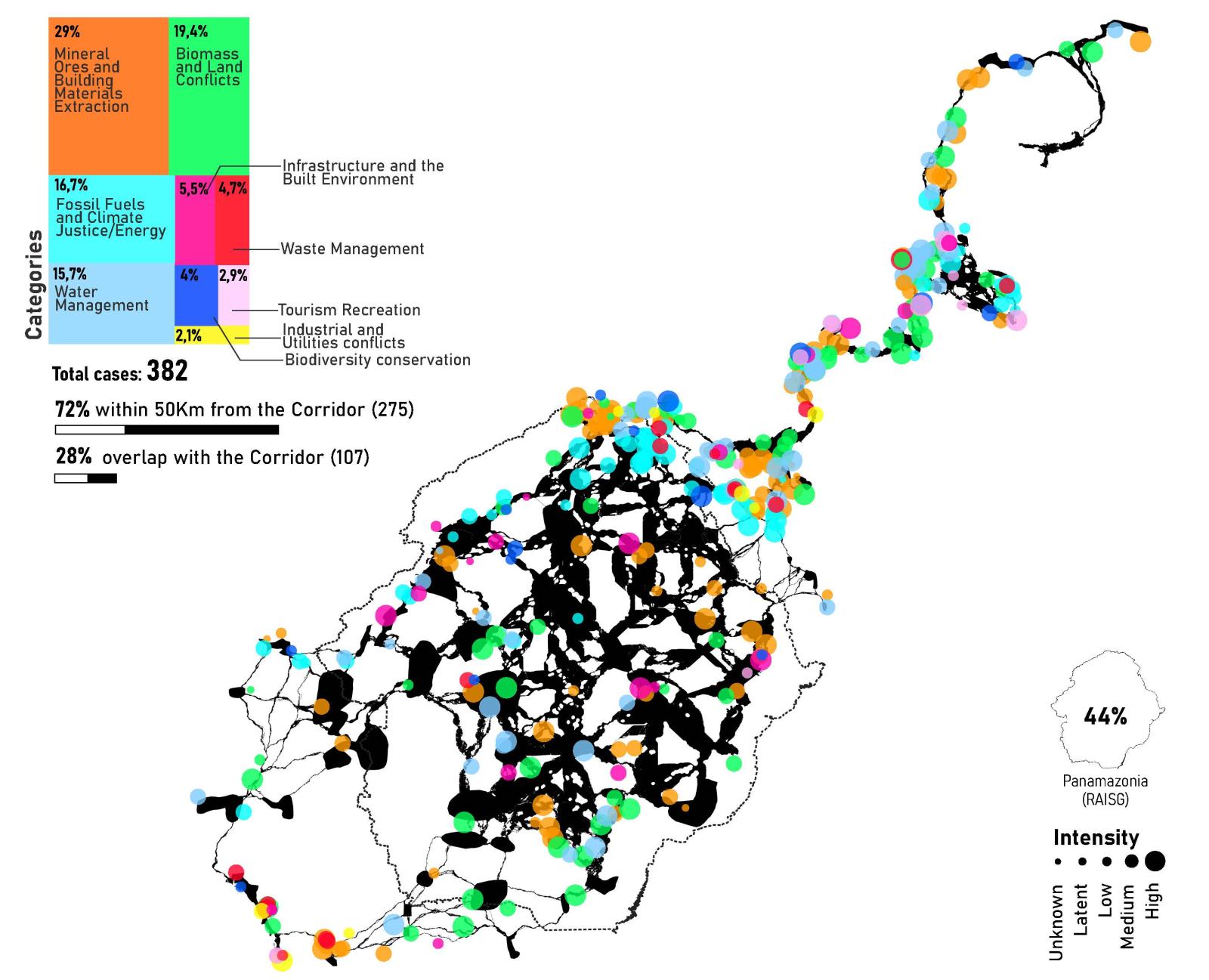

The Jaguar Corridor is a frontier of extraction and waste disposal for the industrial economy—one where Indigenous communities, farmers, and other marginalized populations across the region have struggled and even died for environmental justice and their right to live in these territories. The inventory of the Environmental Justice Atlas, which collects data on ecological distribution conflicts from activists and researchers, shows that over 30% of the cases in the hemisphere are in immediate proximity of the Jaguar Corridor even though the corridor only accounts for 8.5% of the Americas—an indication of the strong mobilizations occurring in these territories. The Amazon, where jaguar life still thrives, has become increasingly critical. Almost half of the Atlas cases occur in this area and are mainly related to land grabbing, deforestation for natural products, itinerant agriculture, and the construction of hydroelectric dams.

A heatmap integrating the most urbanized areas and tree cover loss, as well as the EJA inventory, characterizes the corridor in terms of its frictions for the survival of both the jaguar and the communities living in these areas. Because critical zones are the most detectable fragmented landscapes, these areas of friction can also emerge as potential opportunities to reformulate the terms of cohabitation. Political ecologists Bram Buscher and Robert Fletcher propose the concept of convivial landscape planning as a lens to rethink areas of habitat fragmentation. Rather than setting nature apart, this concept calls to re-embed the uses of non-human natures into social, cultural, and ecological contexts and systems. Doing so, he underscores, entails “learn[ing] to accept both nature that looks a little more lived-in than we are used to and working spaces that look a little more wild than we are used to.”

The cartography of interconnection is a way to move from a general view of the Jaguar Corridor toward a situated understanding. More than a series of untouched natures, or a series of landscapes to be managed by scientists and experts, the corridor is a deeply political and collective project—one embedded in relations of power that define how (or if) the corridor is shaped and cared for, and whose lives are enhanced or diminished by this process. Instead of a fixed landscape, the corridor requires acknowledging and repairing the unequal distribution of environmental consequences caused by processes of urbanization— and the violences these have prompted—as well as embracing alternative practices of cultivation and caring already present and enacted by the peoples living in these areas.

In my spring 2023 seminar, graduate students from the School of Architecture proposed to explore the Jaguar Corridor through the lens of tourism. Tourism is a crucial matter of concern as it is both an economic activity that reshapes territories through the spatial production of logistical and traveler infrastructures, and a commodified experience that is revealing of urbanite desires. The theme chosen allowed each student to navigate significantly different terrains of contestation, following their own curiosity while fostering a rich dialogue between their respective explorations. The result of this work came together in a collective exhibition that carefully sought to communicate their research to wider audiences.

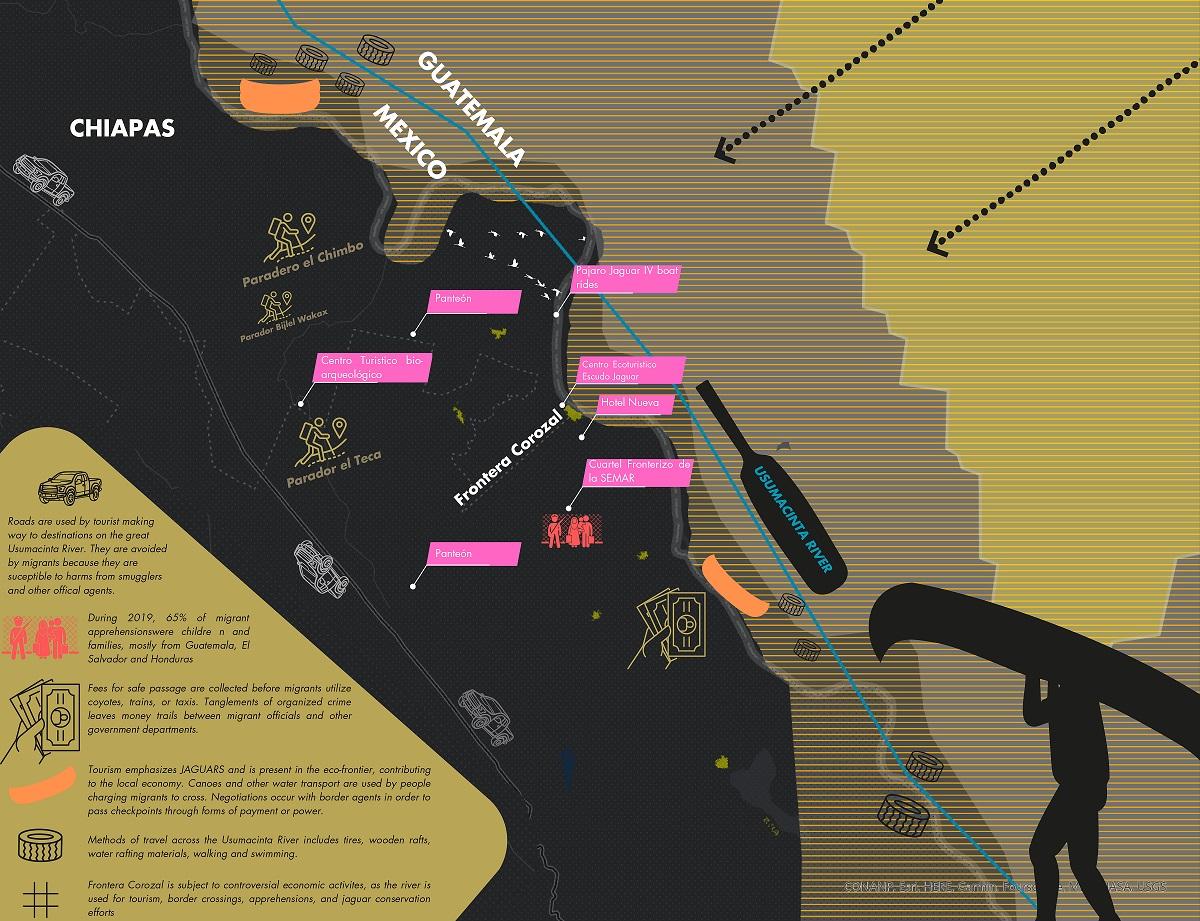

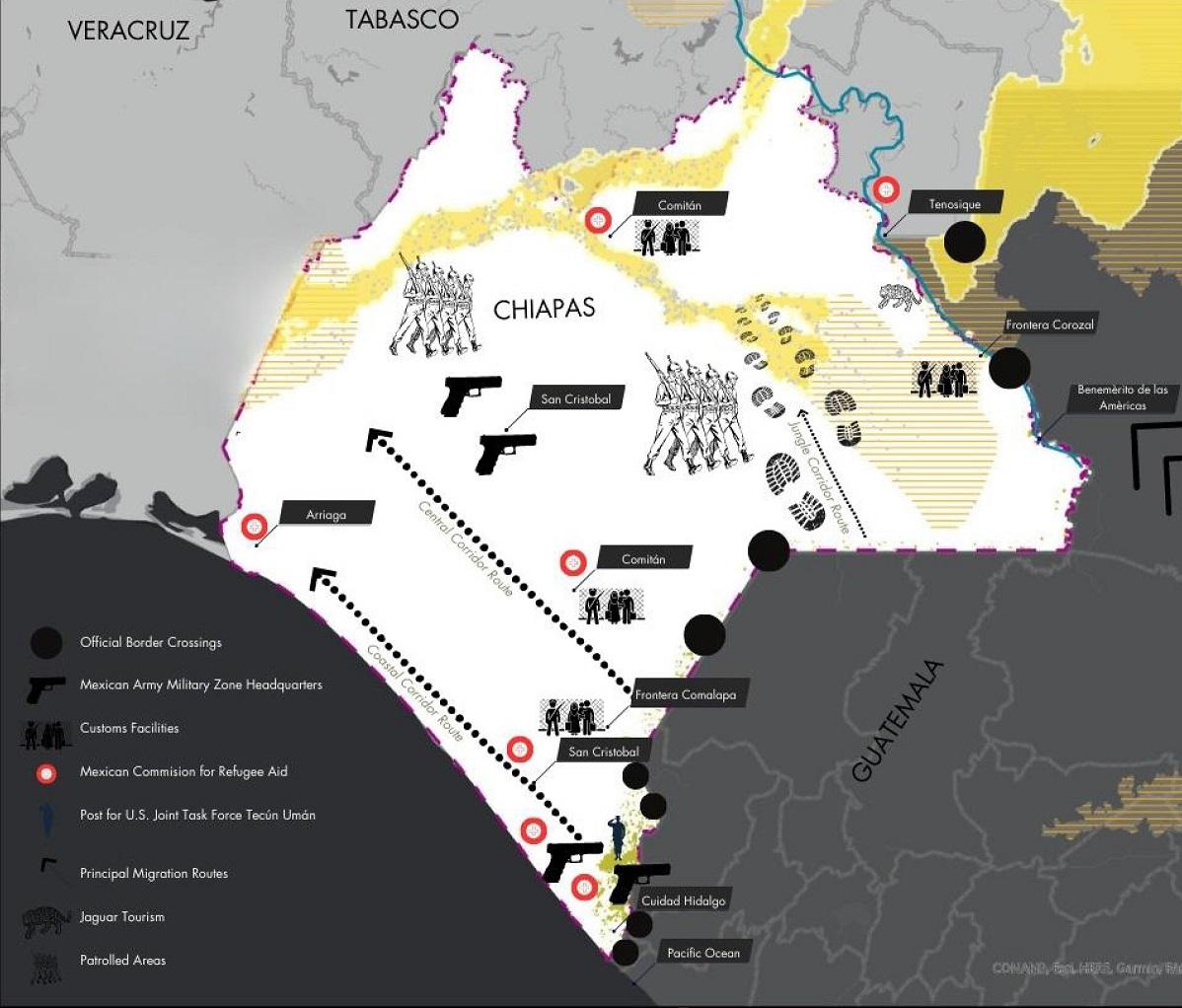

Alejandra Quintana (MSCRP + MSUD ’25) traced the impacts that the Maya Train and its tourist infrastructures—which link cities with Maya temples and other ancient constructions—will have on the Maya Forest—the largest tropical rainforest and main remaining habitat of the Jaguar in Central America—and its Indigenous communities. Naomi Nelson (MSCRP ’23) delved into the growth of Ayahuasca rituals and other types of self-discovery tourism, inquiring if there is a connection between this tourist trend that is increasing in popularity and the illegal trade of jaguar parts. Natalie Raper (MSCRP ’23) explored how the Jaguar Corridor Initiative relies on the cooperation of private landowners in Colombia, where jaguar sightseeing travel is starting to be encouraged in the eastern plains with the aim of replicating successes in the Brazilian Pantanal. Alyson Vargas (MSCRP ’23) examined the adventure tourism and migration flows shaping the Usumacinta River, a contested border between Guatemala and Mexico where jaguar conservation efforts intersect with border politics and surveillance and deterrence infrastructures. Finally, Chaochen Fan (MSCRP + MSUD ’25) followed carbon credits projects in the Acre and Rondônia states in Brazil and the concurrent expansion of illegal logging, questioning whether the promises of many airlines to offset greenhouse gas emissions with an extra fee will actually result in positive change.

Taking the cartography of interconnection as a departure point, each of these projects provides an in-depth narrative of the Jaguar Corridor and its socio-environmental landscapes. This involved recognizing the celebratory stances as well as the dissents and frictions that counter polished narratives of progress—as in the case of the large-scale infrastructures of the Maya Train project—and the seemingly straightforward solutions to environmental breakdown—as in the case of the uncritical spread of new carbon credit projects across the region.

Perhaps what is more challenging—and at the same time, what can be more stimulating—about navigating and narrating these explorations is that they present an opportunity to release the complex set of socio-environmental, political, and economic entanglements at stake. The students expressed that one of the most difficult aspects of their assignment was finding reliable sources, and recognizing the biases that these might reflect. For instance, Naomi Nelson relied on the information provided by Operation Jaguar, which is a non-governmental organization based in the Netherlands that collects data on illegal trade of jaguar parts. Naomi underscored the need to recognize that conservation can easily carry “a smidge of colonization” because the people involved might impart “their own priorities and have the resources to do so effectively without understanding local infrastructure or indigenous knowledge."x One additional challenge, and potential area of further experimentation, pertains to representation. In her research on the Jaguar Corridor on the Usumacinta River, Alyson Vargas focused on the violent intersection of migrants’ experience trying to reach Mexico from Guatemala (and ultimately the United States) and the promotion of adventure tourism in the area. Hers was a first effort to “represent the physical terrain more to show the dangers of it and express to the public how difficult it is to navigate, not only as an animal who’s used to it, but as humans who are forced to use these corridors as a means of survival too.” Facing these challenges in the process of research can provide learning opportunities to rehearse skills of critical inquiry and analysis.

In sum, the premise of this exercise, and of this research at large, is that the Jaguar Corridor might offer us—spatial researchers and practitioners—a rich framework through which to consider urbanization processes and their connection with environmental breakdown and biodiversity loss in a time of deep ecological change. Doing so can push us to decenter cities as the main area of urban inquiry, and enrich our understanding of the multiplicity of living beings that cohabit the world in their own ways. It is also an opportunity to expand the analytical expertise and representation techniques of the spatial arts, to engage in a broader discussion of this initiative, and, further, to imagine and push forward attentive responses based on a multispecies view of nature.

This article originally appeared in the 2023-2024 edition of Platform, "Civics and Placemaking." To view the original version, including end notes, visit: https://soa.utexas.edu/publications/platform/platform-civics-and-placem…

Fig. 1: A stronghold against urbanization. Correlation of the Jaguar Corridor with the dataset of the “Three Global Conditions for Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Use” (2020). Credit: Juana Salcedo

FACULTY:

Juana Salcedo