Q&A with Associate Professor Katherine Lieberknecht

Katherine Lieberknecht researches environmental planning centered around equity, with a specific focus on climate planning, green infrastructure planning, and water resources planning.

She was the inaugural chair of Planet Texas 2050, The University of Texas at Austin’s first grand challenge research program, and continues to serve on its leadership team. She also serves in leadership roles for several externally funded projects, including a National Science Foundation Smart and Connected Communities project focused on community-led climate adaptation in Dove Springs, and the Department of Energy-funded Southeast Texas Urban Integrated Field Laboratory in the Gulf Coast.

Other recent projects include contributions to a National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration-funded collaboration between UT Austin and EcoRise, a green jobs study for the City of Austin, and the 2021 CHCI Global Humanities Institute on Climate Justice and Problems of Scale.

As part of our faculty profile series, we caught up with Katherine to learn more about her research, cross-disciplinary projects, and advice for Texas climate planning.

Much of your research and work focuses on environmental planning, including climate planning, green infrastructure, and water resources. What initially prompted you to pursue a career focused on environmental issues? Why environmental planning, more specifically?

I’ve always been happiest being outside in nature. I grew up in Austin, with a backyard that stretched down to a magical part of Williamson Creek, and my parents and sisters and I spent a lot of time together in parks, hiking, and on the Gulf Coast. While I realize not everyone wants to be out in nature as much as I do, I’ve always felt strongly that people should have equitable access to nature—and even if people don’t want to hike or swim or birdwatch, nature provides lots of other benefits, like clean air and abundant water. And even from (or maybe, especially from) my perspective as a kid, it was really apparent that people in Austin did not (and of course, still do not) have equitable access to parks, or clean air, or lovely backyards where creeks are an amenity—not a flooding threat. My family moved from Austin when I was in high school, and then I lived on the East and West coasts for a while, but I always wanted to come home to Austin and work on changing that environmental disparity that I noticed as a kid.

I didn’t discover planning (as a profession or a discipline) until after college. I was always interested in how humans and the rest of nature interacted and connected, but it wasn’t until I was working for a regional land trust on land conservation projects that I started learning about what planners — and specifically, environmental planners — do. Something I really appreciated about the first planners I interacted with was that when I’d raise questions about equity and fairness, instead of minimizing my concerns, planners really wanted to talk about these challenges — and try to address those challenges in some way — which had not always been my experience in other professional settings.

Although the planning profession has made many mistakes, I really value that many planners try each day to work with communities to improve the health, safety, and well-being of residents — both human residents as well as the rest of nature. We’re not perfect, but, at least in the day-to-day work that I do, I see planning professionals and researchers working together with people to create better futures.

As the inaugural chair of UT Austin’s Planet Texas 2050 Grand Challenge and several of your more recent projects, you’ve been a member of several inter- and transdisciplinary research teams. Could you talk a bit about your experience working at the intersection of so many different perspectives and areas of expertise. What are some of the challenges, and what do we gain by engaging in this type of work?

It may sound trite, but I do believe that we can only resolve the complex, large-scale challenges that we face as a society by working across disciplines and stretching beyond academia’s borders to include people who live and work in the places most impacted by those challenges — whether those challenges be climate-related or otherwise. In other words, these are complex problems, so, at least to me, it makes sense that our solution-making is also going to involve complexity.

So, you are very correct, even though there is a lot of value to this approach. There are also challenges related to research that involve multiple disciplines as well as community members. Some of the challenges I’ve come across in the interdisciplinary (meaningful collaboration across multiple disciplines) and transdisciplinary (meaningful involvement of people from outside higher education) work that I do involve power, communication, and time. There can be very visible yet unstated, power differentials across different disciplines. For example, differences in amounts of external funding (grant money) that different disciplines have access to, differences in the way that society values the knowledge that comes out of different disciplines, etc.

Within the transdisciplinary projects I’ve participated in, like Planet Texas 2050, we’ve spent a lot of time developing ground rules so that disciplines like arts and the humanities have equal footing with physical sciences and engineering. But even creating those ground rules can’t, for instance, eliminate the discrepancy in federal funding that’s available for different disciplines, so we haven’t been able to fully address this challenge.

The same goes for communication. For example, I just spent about 15 hours of work with a group of other researchers and practitioners to try to translate climate data into language that was understandable across our disciplines — and then spent another 20 hours figuring out how to communicate it easily and respectfully to community members. The same goes for time; research that involves multiple disciplines, and especially research that meaningfully involves community members, takes a lot more time than many other types of research — because of the time needed for trust building, for communication, for working together to define problems in holistic ways, etc. And that need for more time isn’t always compatible with university evaluation schedules, or journal article deadlines, or with political cycles, etc.

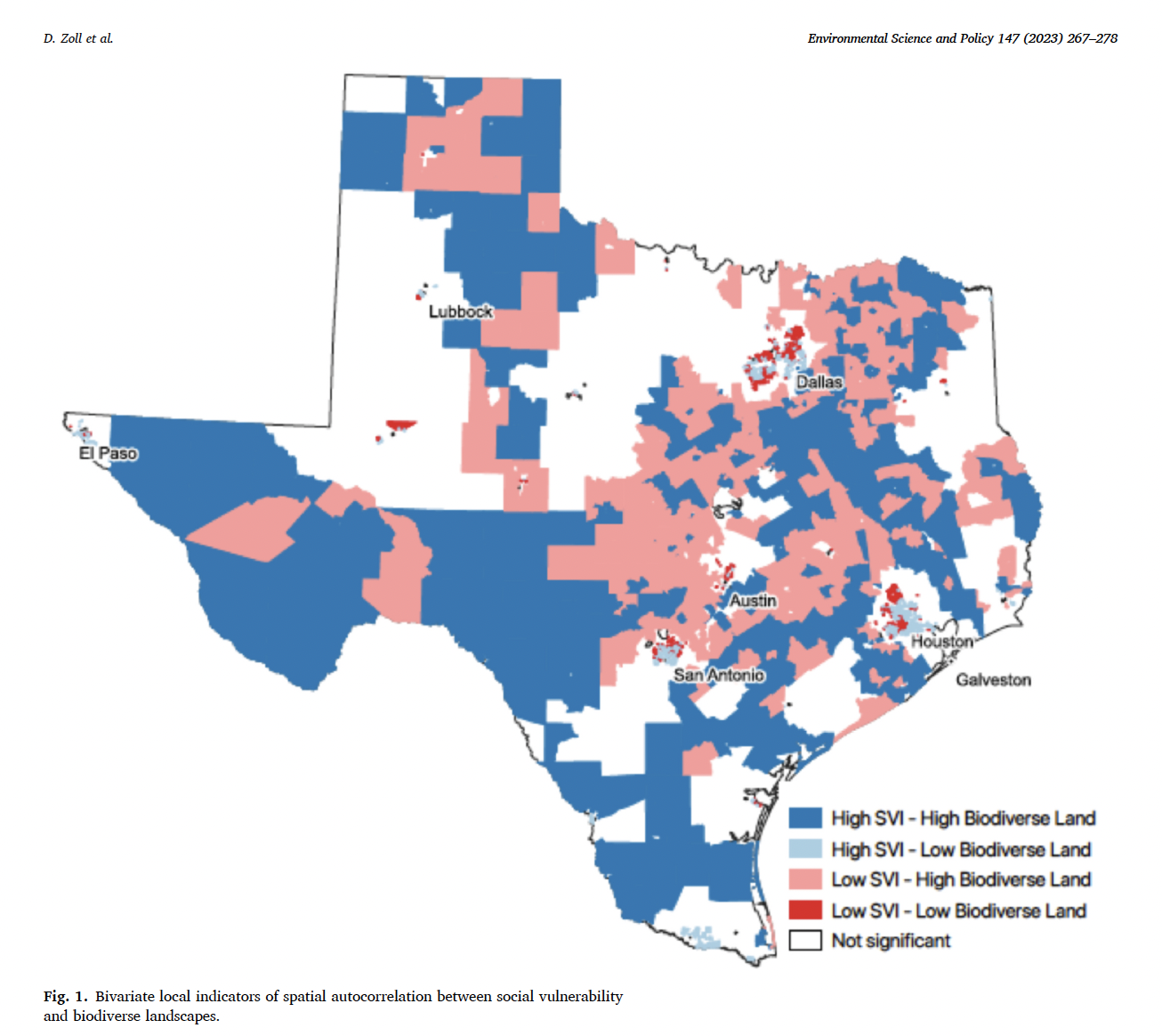

But, challenges aside, we have so much to gain — and have gained so much — from research that breaks down walls between disciplines and between universities and the rest of the world. I’ve been able to work on projects — and help develop what I think are pretty useful research outputs — that I could never even attempt on my own. The work we’re doing in the Gulf Coast with the Southeast Texas Urban Integrated Field Laboratory is a powerful example—we're weaving together cutting-edge air quality measurements, flood models and data, equity data, and climate projections alongside local knowledge held by environmental professionals, community leaders, and residents; only a big, multi-disciplinary, community-engaged research effort could develop this complex of an understanding of the environmental and social conditions of the Texas Gulf Coast — a biodiversity and cultural diversity hotspot entwined with some of the largest-scaled energy infrastructure in the world.

Community engagement, incorporating local knowledge, and “co-creating” with the community are hallmarks of several of your recent projects and papers. Tell us about a project that you think has been particularly successful in this arena, and examples of how you’ve engaged the community in your work.

We are just wrapping up three years of a project based in the Dove Springs neighborhood of Austin. Dove Springs is diverse, socially vibrant, and low-income neighborhood that experiences extreme flooding and urban heat. After Dove Springs experienced a series of severe floods, residents who were working with a community-based organization, Go! Austin, Vamos! Austin (GAVA), expressed the need for an online location to easily find climate preparedness information as well as share knowledge about their community, climate events, and everyday stressors. Our UT team connected with GAVA through shared connections at the City of Austin, and we were able to secure a National Science Foundation grant to work with GAVA to develop a network of residents trained in community organizing and climate preparedness, who we then paid to co-design this website to improve climate-related preparedness, response, recovery, and planning. As the project grew, we realized that we needed an additional community partner who would be able to host and sustain the website and eventually connected with Community Resilience Trust, who will be launching the resident-designed website later on this fall — after four years, dozens of workshops and interviews, and many delicious shared meals. And there have been at least three new babies born to the 30 or so residents with whom we’ve been working!

Some of the things that I value about this project are that: the idea came from the community; that UT was able to build a research project around that community-identified need and then obtain the funding to get the work done; and that, at the end of the project, we’ll launch the website the residents envisioned and also have new knowledge about how residents on the frontline of climate-related events view the challenges, stressors, and potential strategies related to things like flooding and heat. It’s also a good example of how our research pathway and outcomes wouldn’t have been possible without collaboration across disciplines and beyond the university. I could help with the planning and community engagement work, but the project wouldn’t have succeeded without computer scientists, designers, engineers, public health and communication experts, community-based organizations, city staff, and of course the residents themselves.

As communities around the world, including here in Austin, grapple with the effects of our changing climate, what are some climate planning challenges we face here in Central Texas? What advice would you give future planners as they work to address some of these issues locally?

From my perspective, some of our biggest challenges in Central Texas are social and political: while we have lots of local expertise focused on both preventing additional harm from climate-related events, as well reducing our greenhouse gas emissions, we have a big gap in state leadership — and funding — around these issues.

I would encourage future planners here to think about three things:

- Do their best to ensure that any planning system they are working within — housing, transportation, economic development, the environment, etc. — seeks to reduce both greenhouse gas emissions as well as climate risk. We’re at a point when we need ALL planning investments to be “both/and” — not “either/or” — when it comes to climate adaptation and mitigation. For example, when we’re planning infrastructure to reduce harm from climate-related events (like flood infrastructure, cooling systems, etc.), we also need to weave in climate mitigation (greenhouse gas reduction) outcomes and vice versa. What are the ways we can use less carbon when creating these adaptation infrastructures? What are the ways that new adaptation strategies can also move us towards a just transition to net zero greenhouse gas emissions? As we create workforce development opportunities around carbon emissions reduction, can we also make Central Texas safer from climate-related events?

- We have lots of past examples of how planners have exacerbated inequity and injustice, especially during times of rapid change. As we transition Central Texas to a climate-safer and greenhouse gas-neutral future, how can planners anticipate future potential inequities? How can we work to repair existing inequities and prevent additional ones?

- Addressing climate change isn’t always easy work, and it’s going to require a lot of changes, which most of us don’t like. I would encourage future planners in Central Texas to learn more about how planners can adopt practices and frameworks from other disciplines and cultural traditions that help us take action while also acknowledging the grief most of us already feel about these changes. And at least some of that is taking the opportunity to work with and learn from people from different disciplines and who have had different experiences than us — which, back to your earlier question, is much of what I’ve found most gratifying about my work at UT over the past several years. For example, what are the ways that artists and storytellers can help us acknowledge the difficult changes and distress — even heartbreak — entwined with both climate preparation and greenhouse gas reduction?