Q&A with Professor Matt Fajkus

How have your research and creative endeavors evolved since being promoted to Associate Professor with tenure in 2016? Can you highlight any particular works that embody your trajectory?

I’ll first mention that I’ve found there to be a constant process of learning in this discipline and in life. I’m continually humbled by the ever-changing complexities of technology and multiple crises that affect the architectural field, and I aim to adapt as best as I can. Simultaneously, I feel fortunate that I’ve learned a lot and I’ve grown in various dimensions over the years, and I’ve tried to make as much of a positive impact as possible.

Prior to receiving tenure, my scholarly output included journal articles and a book I co-authored with Dason Whitsett, in addition to the work from my architectural practice. Since the tenure milestone, I have focused on the latter, and when it comes to my creative work at MFA, my team is essential, and I’ve been fortunate to work with many wonderful people over the years. I would actually like to specifically credit and name each MFA member, including Sarah Johnson, Ingrid Gonzalez Featherston, Tony Marco, Leah Ferguson, Laine Hardy, Andrea Alvarez Barrios, Dominic Armendariz, Mariano Villareal, and Jack Bigbie. None of this work would be possible without the contributions of their collaborative talent and effort.

A consistent thread throughout the diverse body of work is an interest in expanding boundaries to cross-pollenate ideas, connecting to other systems, and carefully balancing form and function.

A few selected projects might demonstrate the breadth of our recent creative work:

Westlake Dermatology Marble Falls transcends the typological assumptions of a medical office building, designed specifically to not feel like a medical office building, therefore removing the stigma of “going to the doctor.” The building expands boundaries by connecting to broader and larger demographics by challenging typological assumptions by its very form and materiality, therefore increasing health and wellness.

Mount Sharp Residence manifests principles from the book I co-authored with Dason Whitsett, Architectural Science & The Sun, by directly connecting to microclimatic conditions of the site - carefully melding solar response with function, flow, regional materials, and prevailing breezes. The structure is a contemporary model of critical regionalism, balancing the tectonic and scenographic with a tight building envelope possessing passive ventilation capacity, while calibrating views and daylight.

Filtered Frame Dock expands typological boundaries by transcending normative expectations for a utilitarian structure - elevating the potential of a single-slip boat dock. Designed and detailed to last more than 200 years, whereas the average boat dock is replaced every 25 years, the structure is made to be resilient and endure – a fundamental tenet of sustainability. As a passive structure constructed with advanced digital fabrication technology, the dock is an instrument to modulate light and breezes, delicately bridging the ecotone to connect land and water, while framing the wind and sky.

Descendant House is a model for multi-generational housing, accommodating three generations in a single structure, spatially and programmatically composed to allow for common gathering zones and private spaces. The design connects to the site and microclimate by embracing the topography of the site and existing trees, working with them rather than against them. The building’s volumetric massing and apertures balance solar gain while blurring the lines between inside and outside, providing direct and indirect connections to nature.

In your opinion, what change should the field of architecture embrace? How can these shifts be embedded in the early stages of design education?

I believe the old adage “change is the only constant” has never been truer than it is in our current world, with accelerated changes to our built environment, and even more so, to our way of interfacing with it. Rapidly evolving technologies include an exponential growth in digital tools and artificial intelligence, which have made a significant impact on the way we create and think. Likewise, I expect that construction will also continue to change with the advent of digital fabrication and 3D-printing. I feel it’s essential to embrace these technologies, but also to not lose sight of analog tools and critical thinking - maintaining a healthy skepticism of technology and what it offers. If blended well, old and new ways of thinking/drawing/designing can allow for interesting and unexpected new methods of creative problem-solving.

How do you teach architects to be great collaborators and communicators?

As an ever-present undercurrent, I hold gratitude for my parents, who were both great teachers in their own professional right, and to me personally as well. My mother was a special education teacher and later a diagnostician, and my father worked for the Texas Rehabilitation Commission and later for the Texas Commission for the Blind. They both modeled incredible patience, empathy, and the ability to communicate effectively with a wide variety of people. I feel like I can never live up to the exceptional examples they set, but I’m always trying to improve and improve as a person and teacher.

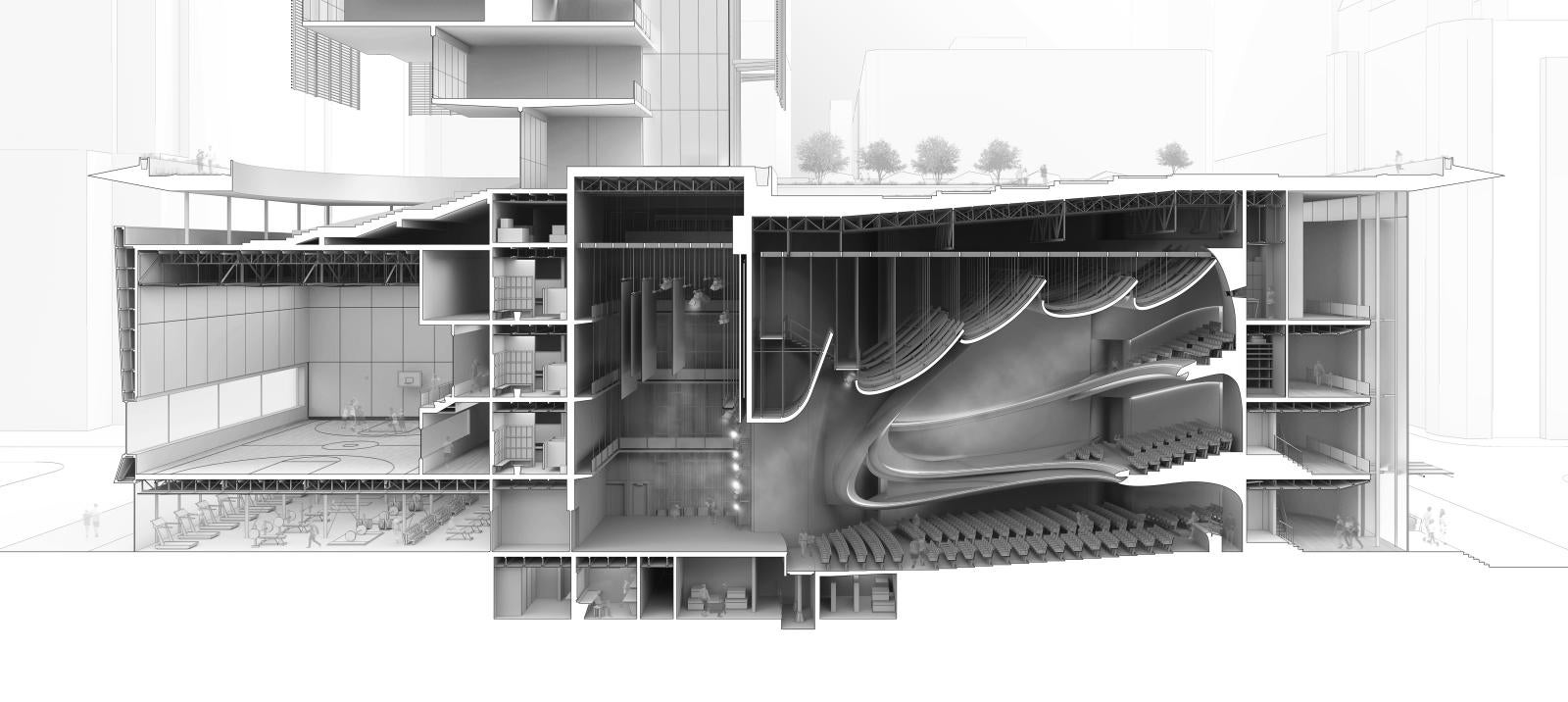

One of the ways I try to teach collaboration skills is simply by structuring courses to include group work and research. In my Light & Sustainable Design class, I intentionally arrange student groups with a dynamic balance of specialties among students, including those that major in not only Architecture, but Engineering, Interior Design, and Sustainable Design. I explain that communication is a key soft skill for students to learn to be prepared to enter the profession, particularly to work effectively across disciplines. Differences in ways of thinking should be embraced, since some of the best designs and ideas in general come from brainstorming sessions, as long as mutual respect and active listening are embraced. The design process is often a negotiation between creative individuals, while considering contexts, economic factors, function, and the human experience. Furthermore, I encourage students to participate in the critique process in my design studio courses, such that they have the opportunity to provide feedback to their peers. I also teach interactive workshops where students are expected to answer contribute to conversations and be prepared to sketch on the spot and synthesize verbal and visual information through representational drawings and descriptions. In my Integrative Design Studio course, numerous student work projects have gone on to win awards and receive recognition, and I believe it’s due to, not in spite of, the fact that students collaborate in pairs throughout the semester to comprehensively design complex buildings.

Why is Austin as a site meaningful for you, personally, to design architectural spaces in? How do you borrow from your childhood memory of growing up here?

I’m a fifth-generation Texan with deep roots in the Central Texas area. My ancestors immigrated from Sweden, Germany, the Czech Republic, and England, and I have since traveled to each of those countries, sometimes to visit family who never left, and I even lived in the UK for five years. Through this lens, I view Austin as a place that is relatively new, as most global cities go, and still in a position to be shaped and molded by architects and creatives. There isn’t a singular or monolithic “Austinite” since the city has rapidly grown as a blend of implants from all over, and I not only embrace that, but I think I’m an embodiment of that, even though I’m referred to as a “native Austinite.” Likewise, my team at MFA is made up of individuals with a variety of backgrounds, bringing unique perspectives to the table, and through our collaborative process, holistic and thoughtful design solutions arise, all while considering appropriateness of place and context. I don’t believe there is a singular “Austin aesthetic” in terms of architecture, nor one building or a series of buildings that define it.

I believe the most defining physical feature of Austin is its connection and access to nature, even if in slivers, despite the rapid densification. From childhood, I have memories of Lady Bird Lake and the sand banks of the Colorado River downstream, picking pecans under the shade of massive tree canopies, and endless hours of playing outside and later in competitive sports – all under big cloudless skies with the occasional distinct smell of rain. I still love the daily cycle of being in both controlled/conditioned environments for teaching and practicing, and being out in the elements for tennis, running, and hiking. My interest in outdoor adventure and immersion in nature expands beyond the Austin area. During the summers, I enjoy mountain climbing through boulder fields, steep glaciers, and reaching challenging peaks in remote parts of the US. The creative work of my practice borrows from this by blurring the lines between inside and outside and creating interstitial zones between the two realms – not only calibrating daylight but enabling deep connections with nature, and ultimately emphasizing wellness.

Westlake Dermatology Marble Falls by Matt Fajkus Architecture; Photo by Charles Davis Smith.

Mount Sharp Residence by Matt Fajkus Architecture; Photo by Leonid Furmansky.

Filtered Frame Dock by Matt Fajkus Architecture; Photo by Leonid Furmansky.

Descendant House by Matt Fajkus Architecture; Photo by Casey Dunn.

Integrative Studio, student work by Luke Slay and Maverick Santon.

Integrative Studio, student work by Ivan Gonzalez and Tyler Koraleski.

Fajkus and climbing team atop Alaska’s Mount Denali, the highest peak in North America at 20,310 feet above sea level, during a 24-day climb in 2023.