Race and Architecture at UT: Researching and Teaching Difficult and Contested Histories in the Built Environment

Battle Hall was constructed from 1910 to 1911 as The University of Texas at Austin’s original Library Building. Designed by renowned architect Cass Gilbert, it set the tone for the classically-influenced, Mediterranean architecture that was a hallmark of Paul Cret’s plan for campus design in 1933. With a new library in Cret’s Main Building, added to the campus in 1933, Gilbert’s Library Building transitioned to other uses over the decades and was renamed Battle Hall in 1973, and became part of the School of Architecture campus in 1979.

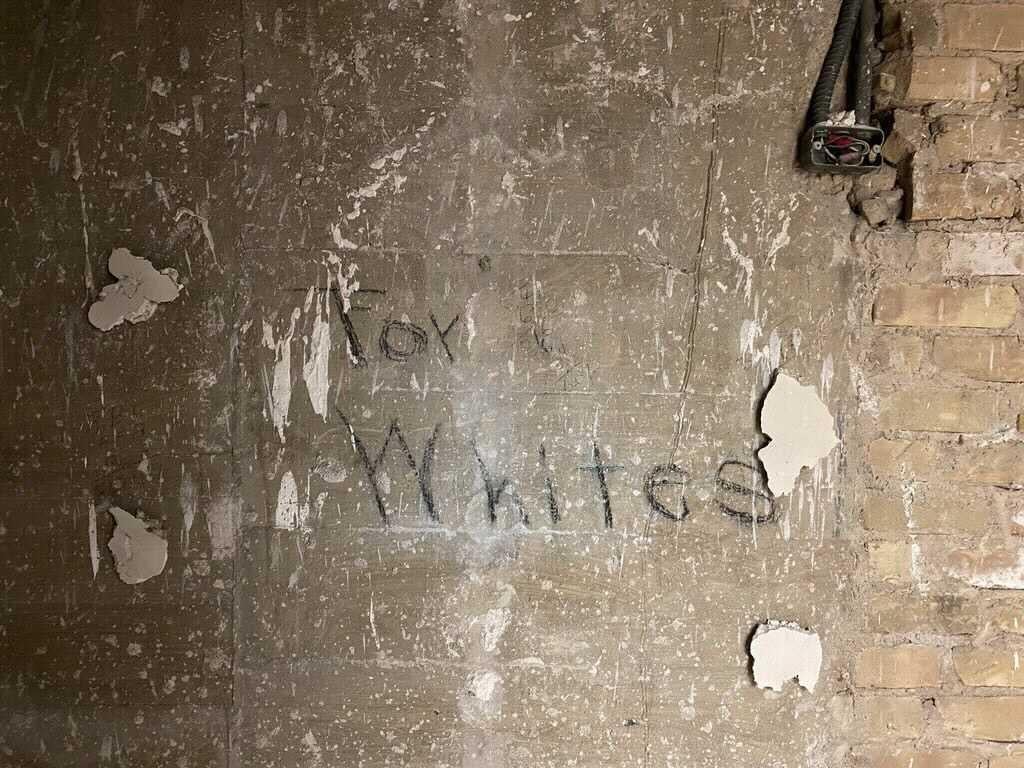

In spring 2021, The University of Texas at Austin commenced renovations to Battle Hall as part of a university-wide infrastructure upgrades project. The work included installation of an ADA-accessible, all-gender, single-user restroom on the ground floor. In mid-May 2022, during selective demolition involving the temporary removal of original marble wall panels in a staff storage space, a member of the design team discovered a handwritten sign on the structural brick wall beneath the marble that reads “For Whites." In concert with efforts of the university’s Contextualization and Commemoration Initiative, faculty, staff, and students in the School of Architecture have conducted research and architectural analysis to support the documentation and preservation of the Battle Hall signage as well as programming to enforce its historical significance and pedagogical impact.

Preliminary Findings: Battle Hall’s Early Racialized History

Given my knowledge of and ongoing research on African American builders in Austin, and interest in the history of campus architecture and interiors, I was notified about the discovery early on. Along with a team of faculty and staff from the School of Architecture and the Vice Provost for Diversity’s Office, as well as consultants working with the project architect, I conducted an exploratory physical examination of the signage and preliminary archival research efforts.

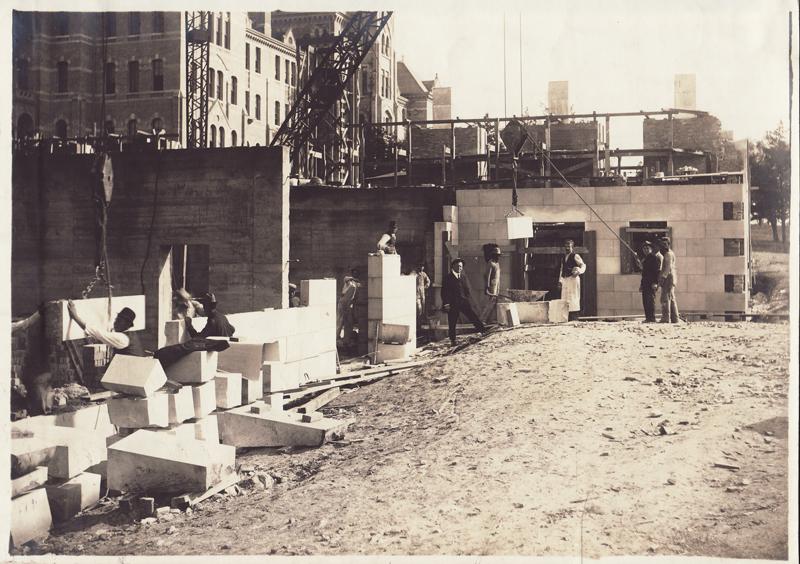

Since the opening of the university in the fall of 1883, the Board of Regents had recognized the need for an independent library building. Not until 1909, however, did then-UT President Sidney Mezes, university supporter “Colonel” Edward House, and New York-based architect Cass Gilbert engage in preliminary discussions that encouraged the Texas State Legislature to approve the necessary appropriations and make new construction on campus possible. On January 11, 1910, Gilbert became the official university architect and accepted the commission for the design of the library project. Excavation began in spring 1910, and the university regents secured James Stewart & Co. as the general contractor that fall. In turn, a number of subcontractors were engaged for specialized work.

Among the laborers involved in the building’s construction between 1910 and 1912 were skilled African American stonemasons who are present in historic photographs. We determined that the signage was written in 1910 or 1911 during the Library Building’s construction to regulate separation between Black and white workers. As mandated in Cass Gilbert’s building specifications, “earth closets” (enclosed temporary dirt-powered facilities along the lines of outhouses or modern-day portable toilets) were to be provided “for the use of workmen of all contractors, without charge” until an appropriate water closet fitted with water and sewage connections was available. Meanwhile, the room where the “For Whites” signage is located was designed as a restroom for the library’s female staff. We can therefore conclude that this space served as a temporary break room and restroom “For Whites” during the building’s initial construction—after plumbing and fixtures were installed but before the future women’s restroom was finished out and the building completed.

As work in the women’s restroom continued, the sign was covered over with the marble paneling. With the construction of the new Library-Main Building in 1933 (the present-day Main Building and UT Tower) the university’s book collections relocated there; the “Old” Library Building functioned in several capacities over the ensuing decades and was named for William J. Battle in 1973. Finally, in 1979, Battle Hall became part of the School of Architecture campus, housing the Architecture and Planning Library as well as the Architecture Drawings Collection (present-day Alexander Architectural Archive). The “For Whites” signage was not seen again until 2021.

Implementing an Action Plan

Following the preliminary research, it became clear that the signage should not and could not be ignored. In accord with the research and pedagogical missions central to the university, I led a task force to develop goals to contextualize and preserve the signage and its historic context. The three-part action plan to meet these goals recommended steps to document and research, preserve and archive, and to teach.

The first component laid out steps to engage in intensive-level architectural documentation and archival research with regard to the signage and its historical and contemporary social significance. With the assistance of the school’s Materials Lab staff, an outside conservator tested the writing substances. The signage was also documented via high-resolution photography and 3D scanning. The archival research has several areas of focus: to chronicle the historical appearance, use, and occupancy of the space; to identify contractors and, specifically, African American craftspeople who were engaged in work not only at the Library Building but across the university’s campus from its founding through its desegregation; and to research the social and economic context of the creation of the signage.

The second part of the action plan presented guidance to preserve and archive the signage and the research around it. The task force and collaborators determined that the best course of action was to preserve the lettering in situ. All architectural and visual documentation and research notes, drafts, and reports will be collected and made publicly available at the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, the primary repository of the university’s history.

The final component of the action plan is to teach—to recognize the significance and pedagogical power of the signage, and to incorporate this discovery and the relevant history into campus contextualization projects such as installing publicly accessible signage contextualizing the writing from 1910–11 as well as developing public programming specific to the racial history of Battle Hall and its construction history.

Student-Centered Methodology and Pedagogy

The research and teaching components of the Battle Hall signage action plan have proceeded under my direction. In particular, they have afforded the opportunity for significant student participation and input that aligns with the development of my research methodologies and teaching practices both inside and outside of the classroom. The discovery of the signage came on the heels of several events—including the May 2020 murder of George Floyd—that highlighted systemic racism in the US, and the university’s responses to those events—including a statement from the student community demanding transformative change, and an action plan from the Office of the President for “A More Diverse and Welcoming Campus.”

Among President Hartzell’s initiatives are plans to honor Heman M. Sweatt (who initiated the landmark Supreme Court case that allowed Black students to attend UT at the graduate level) and to honor the university’s first Black undergraduates. These two tasks are part of what has evolved into UT’s Contextualization and Commemoration Initiative (CCI). The research on and documentation of the Battle Hall signage and its historical and contemporary significance has become one of more than one dozen faculty-led studies to commemorate—to recognize “the people and processes that have made The University of Texas a more inclusive public institution”—and to contextualize—to "situate campus symbols, traditions, and the institution within UT’s historical environment and ethos.”

In order to commemorate and contextualize, the appropriate research is necessary to support this work. That scholarship is all the more valuable when incorporated into curriculum and student-centered efforts. Just as the Battle Hall signage was discovered, graduate students in my summer 2021 African American Experiences in Architecture course had already started to conduct research on the contributions of African Americans to the university’s built environment as an extension of my research and class lectures on Black builders in Austin. Expanding on historic construction photographs and known craftspeople and laborers, they analyzed UT yearbooks, construction documents, newspapers, city directories, and genealogical records to begin to “identify and visualize these anonymous artisans, pinpointing the craft and skill involved in the construction of the University of Texas campus in an effort to honor and appreciate the unrecognized talent of Austin’s early Black community.”

Student research, therefore, has become an integral component of the CCI “Race and Architecture at UT” research team that I lead. Graduate research assistants under my supervision—Vasken Markarian (Ph.D. ‘22), Samantha Panger (MLA ’23), Tolu Oliyide (Ph.D. candidate)—have conducted research at the Briscoe Center, Austin History Center, Texas State Library and Archives, as well as in various online newspaper and genealogical databases. The students do not simply gather research. They present their efforts and findings through written summaries and analyze them using spreadsheets, timelines, and other tools—all of which provide the context that will become the basis for CCI-produced programs and monuments. Perhaps most importantly, they identify data gaps where additional research is needed.

As part of the action plan referenced above, the work conducted by me and the students on the CCI “Race and Architecture at UT” team will form the basis of an archive, housed at the Briscoe Center for American History, that documents the period and the writing found in Battle Hall as well as the relationship between race and architecture at UT. The archive will be accessible online and in the Briscoe Center’s reading room. The center’s executive director Don Carleton assures that “As with all the center’s archives, this collection will be open to scholars and students, meaning it can be utilized for research and teaching.”

Learning Outcomes and Public History Impact

The work of the CCI “Race and Architecture at UT” team ties directly to my scholarship and efforts to teach about and identify African American men and women who contributed to the development not only of Austin, but to the US built environment. As a historic preservation scholar and practitioner, it is my goal that the research and teaching I engage with, and lead students through, also serve as tools for social justice. The task “to educate our students as well as the general public about our institution’s lesser known past” in classroom work and through the efforts of the CCI “Race and Architecture at UT” team have taken on a greater purpose—that of telling the stories of marginalized communities to reinsert them in the historical architectural narrative even when we cannot do so in the physical built environment.

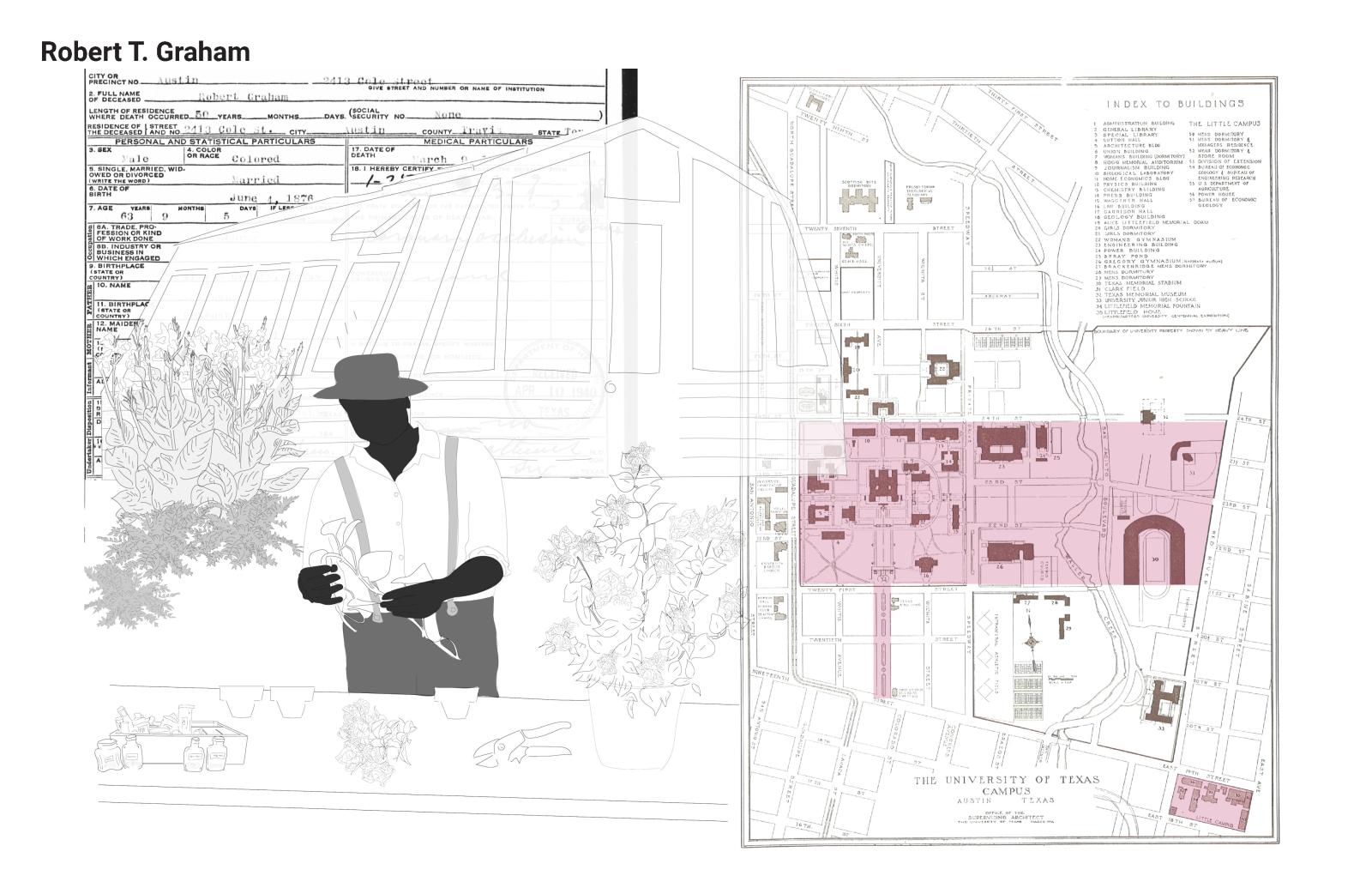

One of my frameworks for pursuing this is for students, as part of their course requirements, to develop and implement research projects with a public-facing end product. The students researching African American campus builders in the summer 2021 course developed a web-based StoryMap. Along with narratives that the student group wrote based on their original research, they integrated historic photographs and contemporary views with “sliders” to compare images between the 1910s and the present. For her previous coursework, Miss Panger had created montages of African American groundskeeper Robert Graham that featured a collage of historic photos and documents and a silhouette to physically represent him; these illustrations were included in the student group’s StoryMap. They, and new montages of African American “University Builders” will be a feature of the exhibition that the CCI “Race and Architecture at UT” team is planning to mount in the school’s Mebane Gallery in spring 2023; the exhibition will be open to the campus community and the general public.

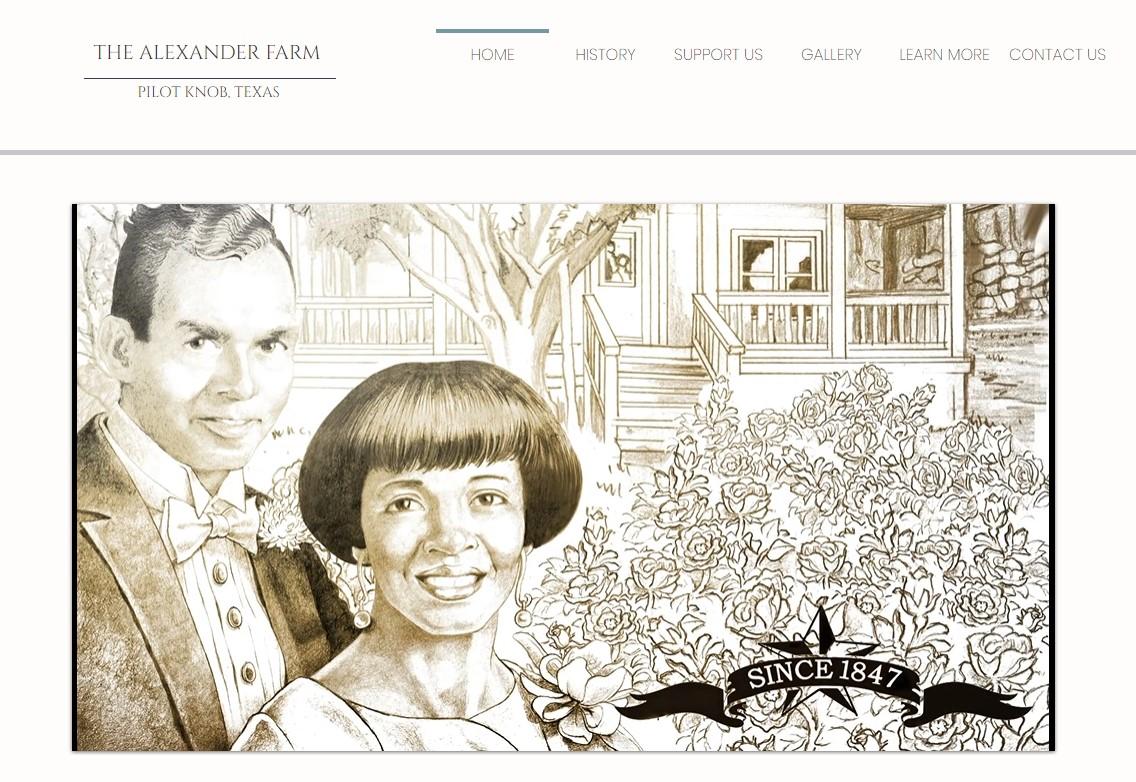

Similarly, student research projects generated during coursework in both my American Architecture course and African American Experiences course has laid the groundwork for ongoing reinterpretation of the Slave Quarters at the Neill-Cochran House Museum.The research we conducted over three semesters was presented as an exhibition and publication, both titled Reckoning with the Past: Slavery, Segregation, and Gentrification in Austin. Another student group has created a website to highlight the continued threats to a historic farm that has been owned by an African American family in Austin for 175 years, documenting the family and property’s history and serving as the basis for a petition and other public notices regarding the farm’s preservation. Students in my courses have embraced my directives to think about what you do not know but that you wish you did…research it…and do something about it.

TARA DUDLEY >>

PLATFORM: TEACHING FOR NEXT >>